To help build a coalition of supporters, a March to End Homelessness took place on April 1 in Downtown Santa Cruz. Organizers said more than 300 people attended. (Christopher Beale — Contributed)

Editor’s note: This is the third story in a three-part series on homeless services spending in Santa Cruz County. Read part one, part two and how this series was made.

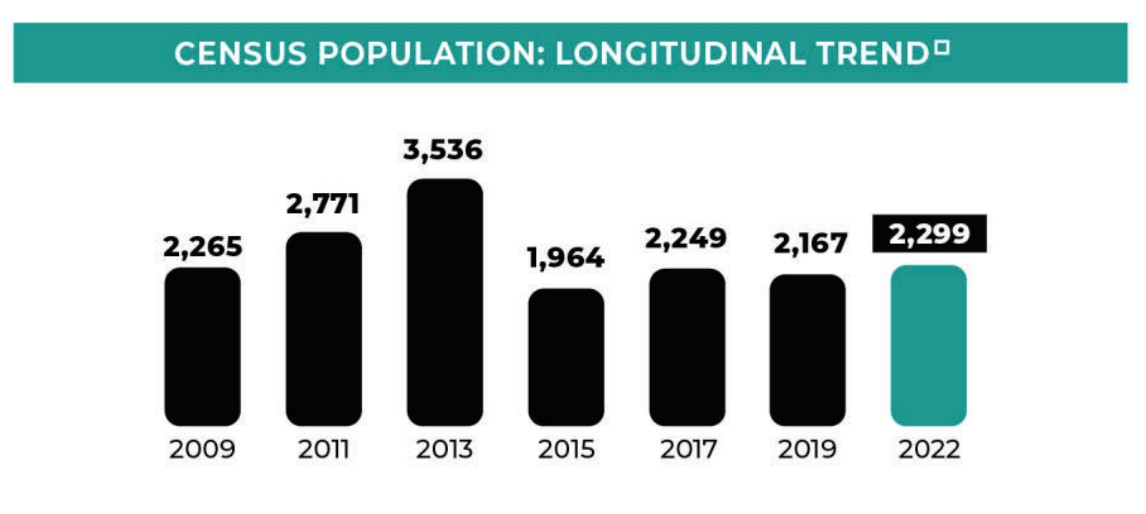

SANTA CRUZ >> More than $120 million was spent on homeless services from 2019 to 2021 in Santa Cruz County, and roughly 2,000 people were homeless at the start and end of that period, according to point-in-time counts.

In each month from July 2019 to June 2021, at least 20 homeless households found permanent housing in Santa Cruz County, and at least 100 households became homeless for the first time or returned to homelessness, according to data from service providers.

With a backdrop of little overall change in the number of unhoused people in that time, were those millions of dollars spent effectively? Why does homelessness persist in Santa Cruz County?

Although many programs feed, clothe, treat or temporarily shelter unhoused people, they do not directly put a person in a permanent home. Money for hotel rooms, temporary shelter, health referrals, administrative costs and public relations are a few examples. Those services can be life saving, especially given the shortage of affordable housing. But they do not solve homelessness.

“The only known cure for homelessness is housing,” wrote Iain De Jong in The Book on Ending Homelessness.

“I’d like to see how many people are using the temporary shelters as a launching pad to getting permanent housing or something, versus people that are just going there and parking themselves,” said Greg Bengtson, who is unhoused and a homeless advocate and mediator.

“If people are evolving in the temporary shelters, that’s not a bad thing. But if people are just being warehoused and staying static, then that’s definitely not helpful,” Bengtson said.

Monike Tone, 43, has been unhoused in Watsonville and Pajaro and has led homeless unions in both areas. When Tone was shown that at least $8.5 million in government money was spent to build permanent housing for unhoused people in Santa Cruz County from 2019 to 2021, she was surprised.

“I would like to know where the permanent housing is, because there’s a lot of people that are elders that would like to receive some of this permanent housing,” Tone said. “It’s better to have permanent housing than to have temporary housing,” she said.

“I was actually part of a program called Families in Transition when I had my kids. It was very stressful because I got to live in a place for six months, but then I spent the whole six months worried about where am I going to move to, right? My hair started falling out of my head because I was so stressed out,” Tone said.

Estimates of unhoused people in Santa Cruz County have been made using point-in-time counts. These “single-day snapshots” typically reflect one-third to one-fifth the households that actually experience homelessness in the course of a year, said Robert Ratner, County of Santa Cruz Housing for Health director. (Applied Survey Research)

Touch this Santa Cruz Local chart to learn about how more than $126 million of local, state and federal government money spent on homelessness in Santa Cruz County from 2019 to 2021. Read more about category definitions, data limitations and money sources. (Kaitlyn Bartley — Santa Cruz Local)

Is the county’s spending mix on homeless services the right approach?

Robert Ratner, director of Santa Cruz County’s Housing for Health Department, oversees tens of millions of dollars from more than 46 sources of state and federal funding to address homelessness in Santa Cruz County.

“It may be too early to fully realize the impact of the investments made” from 2019 to 2021, Ratner said during a county supervisors meeting presentation in February. “There are often lags between the time funds are appropriated, when those funds are spent locally, and when outcomes are possible to measure. Housing and shelter take time to build, and programs take time to hire and train staff, particularly while navigating disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic,” Ratner said.

Asked if the spending mix was appropriate in Santa Cruz County from 2019 to 2021, Ratner said permanent homes are key.

“In general, I think California and local entities spend more money on ‘managing’ homelessness than they do on ‘resolving’ homelessness. This often gets framed as we need to do something in the ‘short-term’ to address the immediate crisis, while we keep working on the ‘long-term.’ In my view, it’s critical to link investments together to an ultimate desired aim/outcome of helping households return to permanent homes,” Ratner wrote in an email to Santa Cruz Local.

The key ingredient to reduce homelessness is to close the gap between incomes and housing costs, Ratner added.

“The core and most helpful investment to address homelessness is closing the gap between the costs of housing in a region and the incomes of those that are homeless or at-risk of homelessness,” Ratner said. “More funding needs to be devoted to covering this ‘cost’ gap on a medium- or long-term basis.”

Rayne Perez was the county’s homeless services coordinator from January 2016 to August 2021. She applied for and managed dozens of state homeless services grants worth millions of dollars.

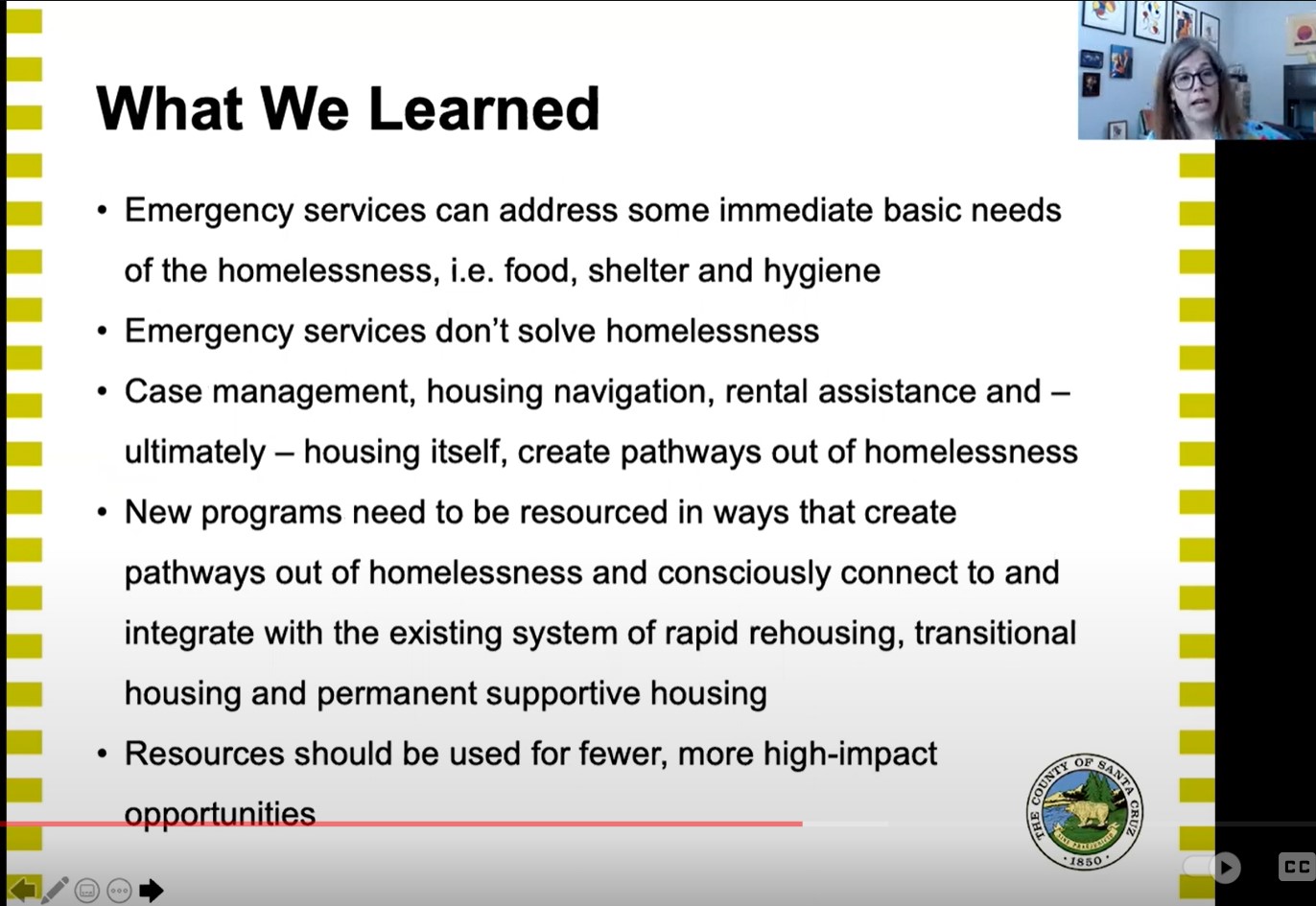

When asked if the homeless services spending mix from 2019 to 2021 was appropriate and reflected county and city leaders’ goals, Perez said that opening a navigation center was a worthwhile goal that was not realized. Shelters during that time typically did not have housing navigators or case managers working with people to find permanent homes.

Looking at the overall mix of spending on homeless services in Santa Cruz County from 2019 to 2021, Perez said she would consider putting less money toward temporary housing and more money toward prevention and “rapid rehousing” that helps unhoused people find homes, help with moving and provides case management.

Brooke Newman, a former Santa Cruz homelessness response manager and Downtown Streets Team manager, agreed. “What needs to be baked into sheltering, if nothing else, is case management and building those relationships with folks,” Newman said. The case managers must be trained professionals who are appropriately compensated. Other shelter staff also should have training and appropriate pay. “There are people who are living in one shelter and working at another shelter. I mean, it’s craziness,” Newman said.

For people who have been homeless several times in their life and for extended periods, finding and keeping permanent housing typically requires support.

“If you just plop someone in — I’ve seen that happen — frequently it does not last,” said Newman.

“There’s so much trauma that has happened to them. Getting connected and building relationships and navigating bureaucracy and helping create some pathway of stability into [housing] is nothing but a net benefit,” Newman said.

During a May 2021 online presentation on more than $9 million spent in the Homeless Emergency Aid Program, Rayne Perez said that programs should focus on paths to housing. (County of Santa Cruz screenshot)

Newman and The Rev. Joseph Jacobs of the Association of Faith Communities in Santa Cruz County said many unhoused people they worked with have been in their 60s or 70s or older. The Association of Faith Communities’ SafeSpaces program allows people to park overnight in 12 church parking lots on a rotating basis. It started about four years ago.

“This idea that people are just flocking to Santa Cruz from other places because there’s free whatever here — not really,” Jacobs said. “In my experience, 80% of people in SafeSpaces are from this area.”

In a 2022 survey of 333 unhoused people in Santa Cruz County, 89% of respondents said they lived in the county when they became homeless. More than 40% had lived in the county for 10 years or more when they became homeless, the survey reported.

“We’re really pretty terrible at helping our elderly,” Jacobs said. He said some people who live in their cars were renters in Santa Cruz County for decades before their landlord sold their home. Others were homeowners who could not pay mortgages.

“Many people in our society are very leveraged and are just one medical emergency or one little trauma away from losing it all,” Jacobs said. “It’s not just about, did we spend the money correctly? It’s a crisis of consciousness.”

Larry Imwalle, now the city of Santa Cruz’s homelessness response manager, said shelter capacity and safe parking spaces were important. “The goal is not just shelter,” Imwalle said, “but really to help build pathways towards more productive housing.”

Imwalle also said that case management, housing navigation and a goal to have a mobile crisis-response team to respond to mental health crises rather than police remained important.

Why does homelessness persist in Santa Cruz County?

Becoming homeless is often the result of a combination of factors. Eviction and job loss were the most commonly cited primary causes of homelessness, followed by a family breakup, drug and alcohol use, medical issues and rent increases, according to the 2022 survey in Santa Cruz County.

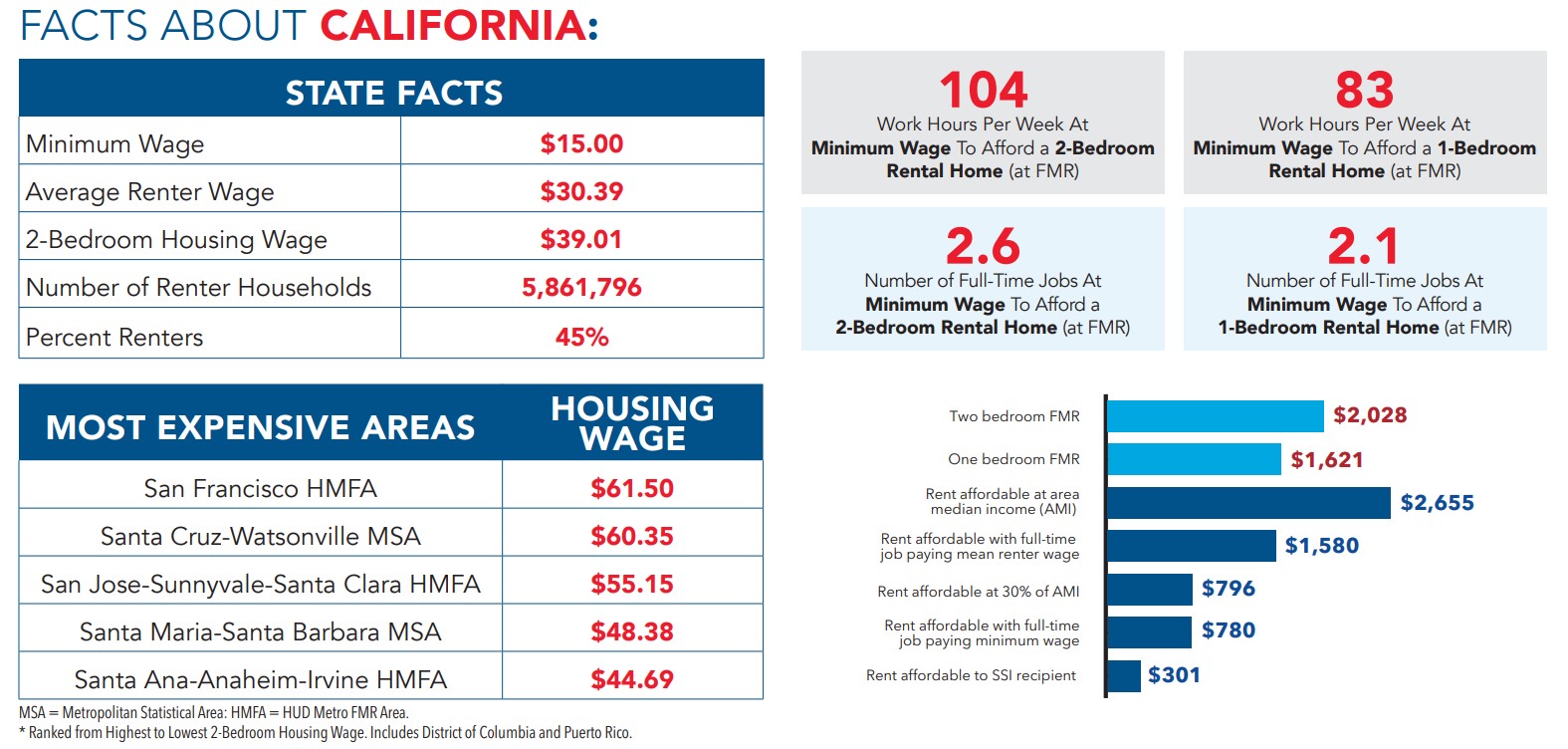

Santa Cruz County’s extremely expensive housing market makes it even harder for people to get or stay housed.

- Rents are high relative to incomes.

- There is a lack of small apartments and other inexpensive places to live.

- The area’s climate, culture and coast make it a desirable place to live.

Santa Cruz County has the second-highest housing costs relative to incomes in California, according to research from the National Low Income Housing Coalition. (National Low Income Housing Coalition)

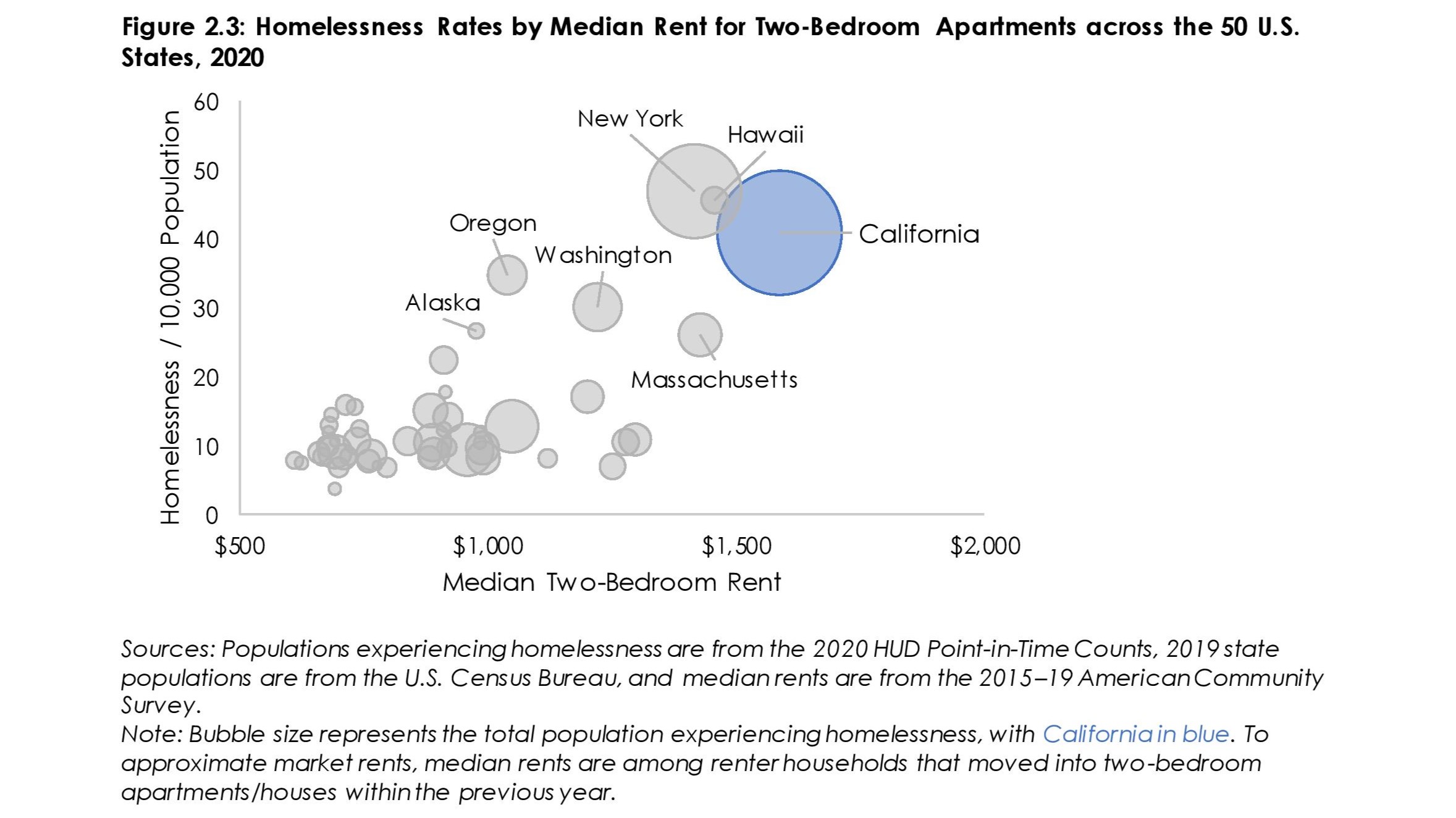

Homelessness is higher per capita in states like California, Hawaii and New York where median rents are higher. (California Interagency Council on Homelessness)

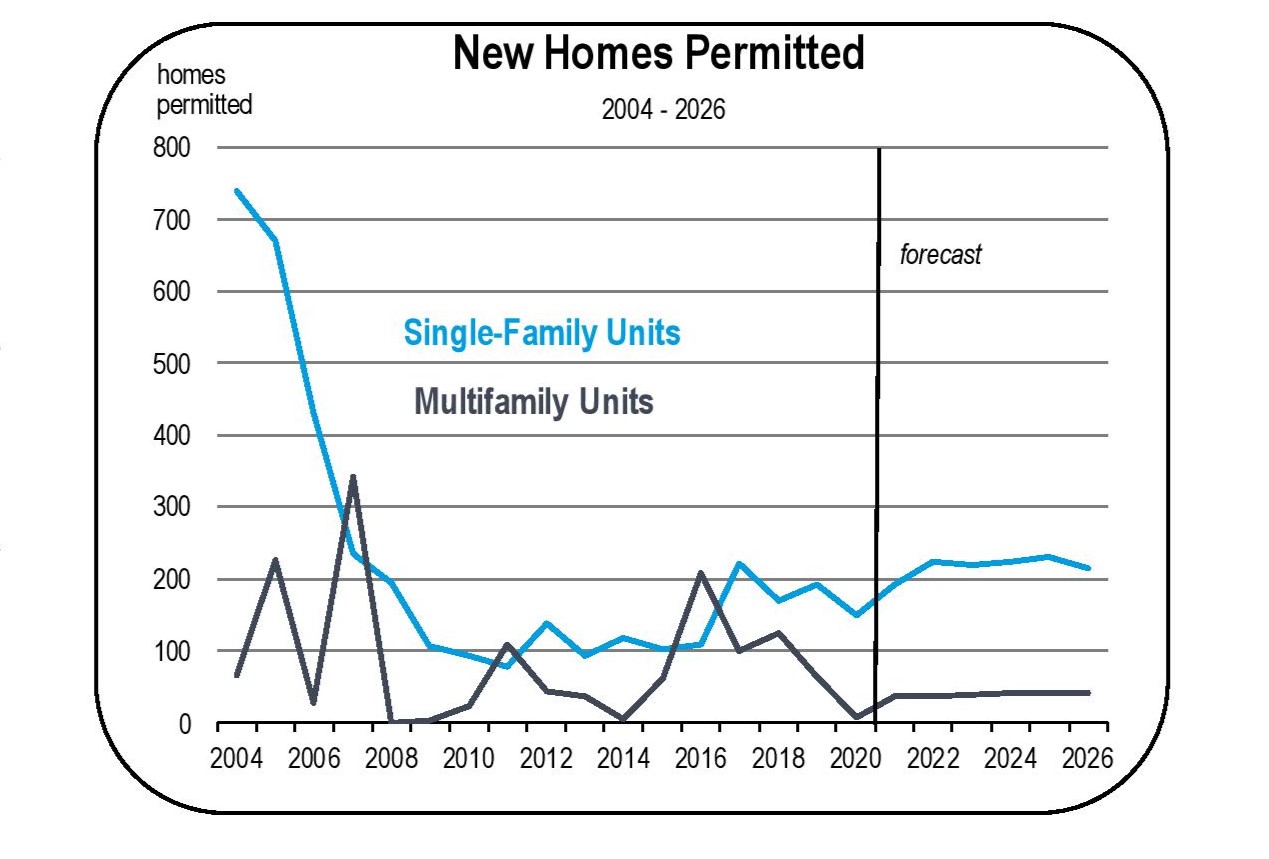

A chart shows new homes permitted in Santa Cruz County from 2004 to 2020, with projections. (California Department of Transportation)

Because of the lack of smaller, less expensive housing, some county and city leaders have said that trying to house the homeless is like a game of musical chairs. As one person finds a home, another person loses their home — and there aren’t enough homes to go around.

Although residents’ idea of an unhoused person might be a single man who has mental health and addiction problems on a sidewalk, about half of the 2,060 people in Santa Cruz County who accessed homeless services in Santa Cruz County in 2022 were in families with children.

- About 29% of unhoused people in Santa Cruz County live in a car or RV, according to a 2022 point-in-time study.

- About 20% of the unhoused people had jobs, 14% were veterans and 38% had been in foster care, the study suggested.

- There are unhoused seniors, people with disabilities, domestic violence survivors and young people aged out of foster care.

- Unhoused people in Santa Cruz County also are disproportionately people of color, according to studies from Watsonville-based Applied Survey research.

A movement toward housing

Permanent housing development has become a focus of the state’s efforts to reduce homelessness.

Called a “housing first” approach, programs are supposed to be aimed at helping unhoused people find permanent homes through case management, rental assistance, move-in money, incentives for landlords and other strategies.

Some Santa Cruz County groups that have focused on humanitarian efforts rather than permanent housing have found themselves with less money to operate programs in recent years.

“More and more, grant funding demands that programs have a housing-first focus, despite the fact that housing isn’t available in Santa Cruz,” wrote Brent Adams, in a news release this year that announced the end of the Footbridge Services Center and Secret Garden Women’s Shelter.

“The poorly conceived and managed funding paradigms of local governments, in contrast with the establishment of repeating mega-camps, has created an illogical contradiction in our community that has driven people away from donating to and volunteering for needs-oriented programs such as ours,” Adams wrote.

Homeless services spending in Santa Cruz County historically has not been coordinated and not necessarily oriented toward permanent housing. Services in the 1980s, for instance, included a soup kitchen and programs through churches and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

“It just kind of got cobbled together,” said Don Lane, who served on the Santa Cruz City Council from 1988-1992 and 2008-2016.

“You had more services and more things happening for people, but it was still all over the place and there was no formal connection between these things. And some of them didn’t have the same goal. Some people really didn’t care if people ever got housed, they’d say, ‘I just want to give lunch,’ you know?” Lane asked.

“For 30 years, roughly, that’s how the system evolved,” he said.

Local leaders’ mindsets are starting to change with a shared goal of permanent housing.

“Now we have gotten to this point where there’s a much bigger recognition that always, we have to be thinking about housing as part of every solution. Like you can do all these other interventions, but if a person doesn’t end up in housing, they’re still homeless, and then we still have homelessness,” Lane said in 2021.

A few dozen people gather outside Santa Cruz City Hall on March 9, 2021, to protest a proposed law to limit homeless camping. (Natalya Dreszer — Santa Cruz Local file)

“A lot of people are very committed to this idea that if we just had a better mental health system, and a better substance-use-disorder treatment system, then that would really take care of the homeless, you know, a big part of the homelessness problem and some of the most difficult parts of it,” Lane said. He said he didn’t want to minimize those interventions, but even residential treatment often ends after a month.

“They still don’t have a home, so they go back to living under the bridge. And what are the chances of that intervention lasting?” Lane asked.

More than 1,400 apartments and condos are under construction and planned for several properties in Downtown Santa Cruz. Some units will be deed restricted affordable, others are studios that are less expensive to rent by design.

New housing in Santa Cruz County

UC Santa Cruz has plans to build 3,000 beds of on-campus housing. The projects have been stalled by lawsuits but are moving forward with construction planned to start in early 2024.

Even if many more students live in new Downtown Santa Cruz apartments before campus housing is built, Lane said he still believed that fewer students would live in crowded rental houses and help open housing options for non students.

“If we had like 2,000 more or 3,000 more places for people to live, that’s going to make the whole rental market — it doesn’t mean that it’ll be easy — but it would be a lot better than it is right now for both people at the very bottom and even just middle-income people,” Lane said.

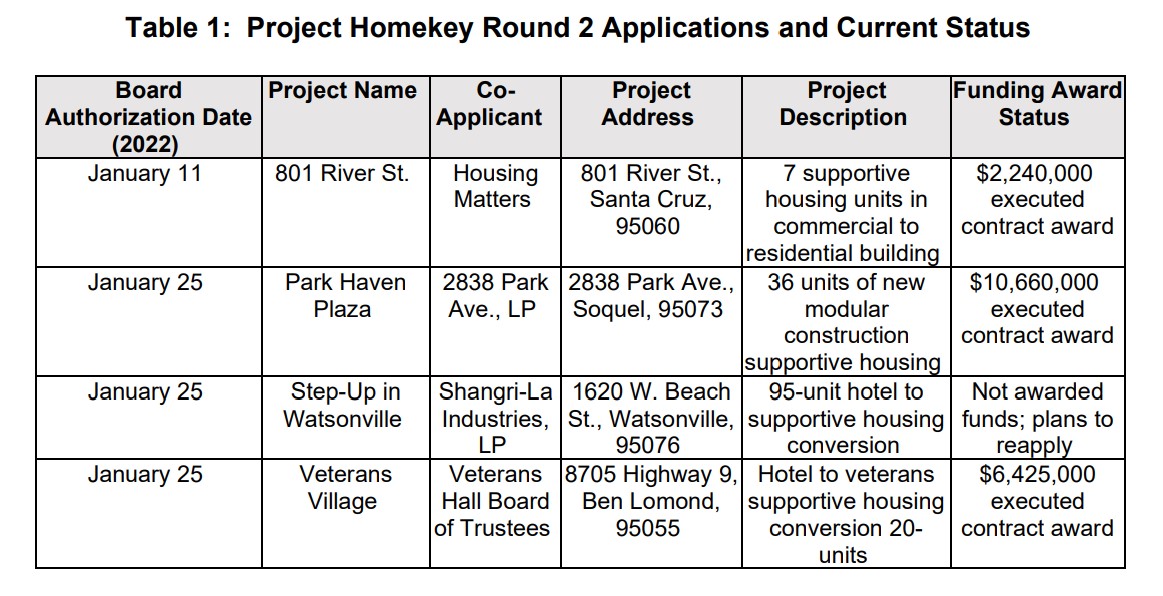

Since 2021, state money has powered new Project Homekey developments like at 2838 Park Ave. in Soquel that will construct 35 permanent supportive housing units for formerly homeless residents Other housing projects aimed at unhoused residents are in the works in Santa Cruz County, like the Veterans Village project in Ben Lomond and 120 studio units at 119 Coral St. in Santa Cruz.

County staff said in February that they hope to secure grants for at least two more Project Homekey housing projects in 2023, in part because of a lack of permanent supportive housing for people with disabilities and other health problems. (County of Santa Cruz)

“I would like to see permanent housing,” said Tone, the South County homeless organizer. “And funding that would actually be out there to outreach, to make sure that everybody in need does get the help that they need.”

Tone added, “But if they’re told to believe that they don’t matter, all they’re going to do is continue not to matter, or not to want to matter, you know? Until our cities can uplift each other, and uplift what’s going on, then it’s not gonna be any better.”

Santa Cruz Local writer Tyler Maldonado contributed to this report.

Read more in this series

- Part 1: From shelters to rent help, 14 categories of homeless services spending in Santa Cruz County traced from 2019 to 2021

- Part 2: Money sources, constraints and problems with homeless services spending in Santa Cruz County

- Glossary of homeless services spending categories and money sources

- Editor’s note on how and why this series was made

Learn more

- Santa Cruz Local’s Solutions to Homelessness series

- Podcast: How Santa Cruz County could solve chronic homelessness — Dec. 17, 2021

- Homelessness survey reveals some common ground in Santa Cruz County — Oct. 8, 2021

- Podcast: Homeless and formerly homeless residents discuss solutions in Santa Cruz County — Nov. 19, 2021

- Strides and stalls in Santa Cruz County homeless plan — Feb. 28, 2023

- Shared data, goals in Santa Cruz County’s plan for homeless — March 10, 2021

Questions or comments? Email [email protected]. Santa Cruz Local is supported by members, major donors, sponsors and grants for the general support of our newsroom. Our news judgments are made independently and not on the basis of donor support. Learn more about Santa Cruz Local and how we are funded.

Stephen Baxter is a co-founder and editor of Santa Cruz Local. He covers Santa Cruz County government.