SANTA CRUZ >> County supervisors on Tuesday approved a three-year plan to reduce the number of unsheltered households by half in the next three years, while acknowledging that the county is about $25 million short of what it needs annually to fund its broad-reaching plan.

The Three-Year Strategic Framework to Address Homelessness is a series of 6-month plans that try to unify the efforts of city, county and community groups in the county.

- The first six-month plan includes a new public data dashboard to track figures like the number of shelter beds provided by government and non-government agencies in the county.

- The first six months also calls for county staff to draft protocols for “encampments” throughout the county

- It also aims to track progress toward building more homes for low-income households, creating more temporary shelters and reducing the time it takes to transition people from temporary shelters to permanent homes.

- Santa Cruz County needs about $65 million annually to achieve its goals to house and provide services to get people out of homelessness, but it now has about $40 million excluding Federal Emergency Management Agency money. County staff said state and federal leaders must be lobbied to help make up the difference.

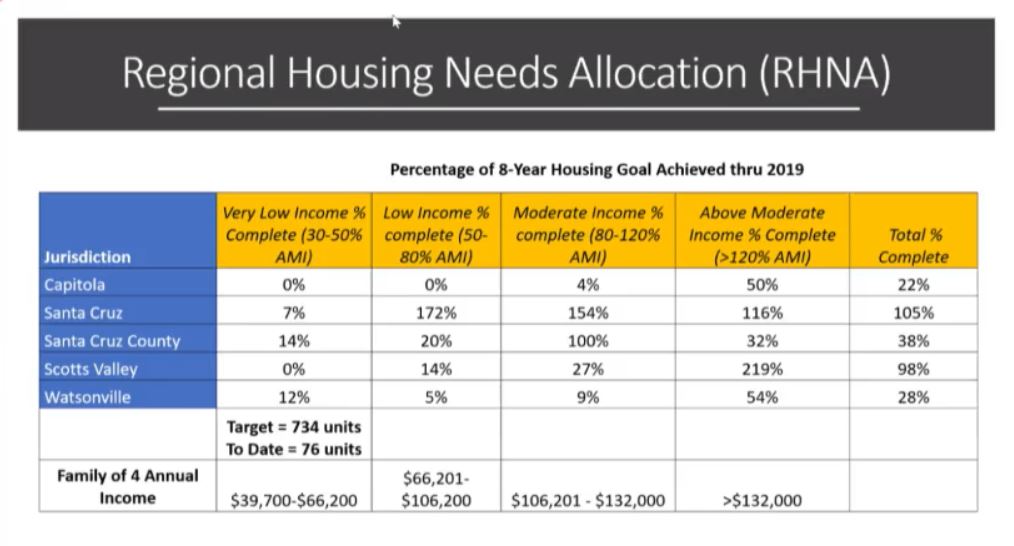

- The biggest gaps in the county’s funding sources are for 600 beds in shelters and transitional housing and 734 units of affordable housing for “very low income” residents as outlined by the state’s Regional Housing Needs Allocation for Santa Cruz County.

“Homelessness truly is a humanitarian crisis,” said Randy Morris, director of the county’s Human Services department, at Tuesday’s supervisors meeting. “We have hundreds and hundreds in this community — thousands — of people who are parents, and have siblings, and have friends they’ve lost touch with, who are living unsheltered. This is a very serious crisis with an awful lot of suffering. And I just hope that throughout our work we can constantly remember that.”

Morris said there was a “history of resistance in the county” to deal with the homeless crisis before Carlos Palacios was appointed county administrative officer in 2017. “This is something that has arguably devolved over many, many decades from action and inaction of all levels of government,” Morris said.

A main driver of homelessness in Santa Cruz County is the difference between residents’ income and the cost of housing, said Dr. Robert Ratner, the new director of the Housing for Health Division of the county’s Human Services Department.

The people most vulnerable to homelessness have “extremely low incomes” compared with the area median income. They are the most burdened by the cost of housing, and 75% of those county residents spend more than half of their incomes on housing, Ratner said, quoting a study by the California Housing Partnership. The county needs about 10,000 more units of affordable housing to meet that need, Ratner said.

“We really need to direct our attention to creating more income growth opportunities and affordable housing for that population if we’re really going to prevent and end homelessness,” Ratner said.

Supervisor Ryan Coonerty called homelessness “a national crisis that’s precipitated by a failure of a safety net, failure of mental health, substance abuse treatment, housing,” Coonerty said. “We’re sort of the last resort response of a result of big system failures.”

Some of the major goals of the three-year plan include:

- A 25% reduction of the roughly 1,405 households experiencing homelessness in the county by January 2024. That includes people in shelters and on the streets.

- A 50% reduction among the roughly 1,000 unsheltered households in the county by 2024

- Improve the effectiveness of programs to help people secure housing, measured in part by the number of days a person spends in a temporary shelter

- Expand permanent housing

- Expand capacity within the homelessness response system

- Build a coalition of stakeholders in the county

- Prevent homelessness with rent assistance, connections with landlords and other means

- Increase connections with programs, services and temporary housing

Paths to solutions

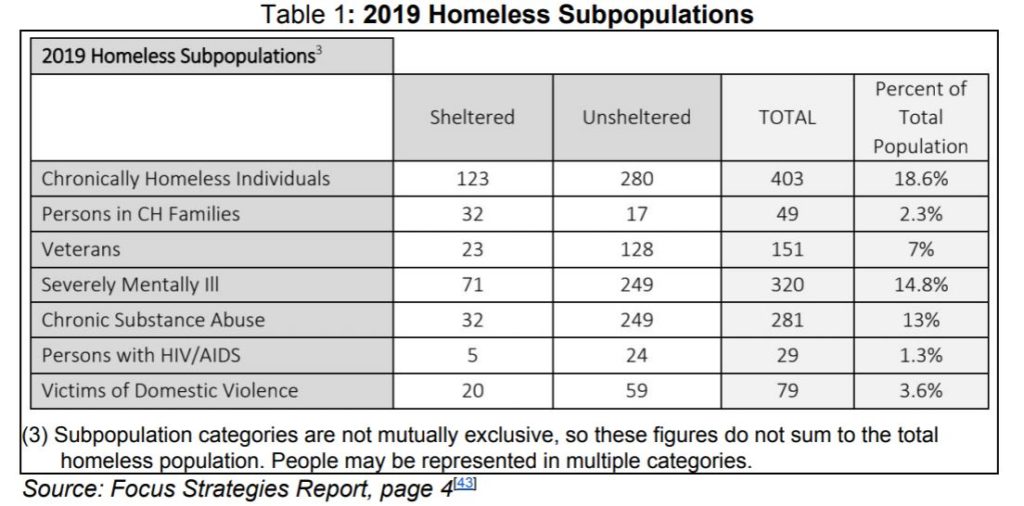

Similar to successful efforts to house the homeless in Bakersfield, county staff hope to create an internal database with a name, photo and story of each homeless individual so service providers can be on the same page. Plans can then be created for “subpopulations,” such as the roughly 80 homeless veterans in the county, or homeless adults with children, Ratner said.

Ratner, the Housing for Health director, said in his former position in Alameda County, county staff found permanent homes for about 400 people who were living in hotels during the state’s Project Roomkey plan during the COVID pandemic.

The supervisors voted unanimously to adopt the three-year plan, have staff return in August for the first six-month update and every six months thereafter. County staff also plan to return to the supervisors at their March 23 meeting with a package of rehousing efforts for people whose shelter space or temporary housing will soon expire because COVID-related funding will end.

Separate from the Three-Year Strategic Framework, the supervisors also voted unanimously to develop more potential places for temporary shelters and safe sleeping sites. County staff already is working on potential temporary housing at the county’s Watsonville Health Center at 1430 Freedom Blvd., Ratner said.

Supervisors Ryan Coonerty and Manu Koenig proposed that county areas outside the “urban services line” be earmarked for 120 units of housing, shelter beds, tents sites or other forms of shelter. Coonerty said Santa Cruz city residents have been most impacted by homelessness. The urban services line is essentially unincorporated county areas that have septic tanks rather than sewer lines.

Supervisor Zach Friend said that limiting the new units to unincorporated areas might mean that, say, church leaders in Boulder Creek that wanted to provide shelter or housing would not be included in the plan.

Supervisor Bruce McPherson also said he wanted to be sure county parks would not be included in any plans to house the homeless because he said they were “hard fought” for recreation. The supervisors voted for staff to come back with a report on potential housing and shelter sites outside the county’s urban services area and outside county parks.

Tiny homes and backyard units

Supervisors moved forward with county staff’s plan to update rules around “tiny homes” of 400 square feet or fewer with an update to its accessory dwelling unit law this summer.

Tiny homes could be on wheels or on a foundation, but several parts of the law need to be clarified if they are legalized as permanent homes. Questions remain on whether tiny homes would require sewer and water hookups, where they would be allowed on steep lots, property setbacks and other details.

During public comments, a Ben Lomond business owner and survivor of the CZU Lightning Complex Fire said she had lived in a tiny home for nine years. She called tiny homes an amazing option for people across income levels.

Part of the purpose of the new rules would be to speed up rehousing efforts among the more than 900 homes that were destroyed in the August and September wildfire.

Supervisor Koenig also pushed to have the county allow pre-approved plans for backyard units, or ADUs, similar to cities such as Seaside. The move could make it easier for homeowners to build or use the document templates to quicken the pace of permit approval.

Supervisor Zach Friend had suggested the same idea years ago based on San Diego County’s pre-approved ADU plans, but county planners provided an ADU toolkit instead. County staff said pre-approved plans could be easier now in part because many other cities and counties have them.

Staff planned to return with an update in late April and a potential update on the law in June.

In other news

Supervisor Koenig appointed his staff member Amy Miyakusa as his alternate on the Santa Cruz County Regional Transportation Commission. Miyakusa was a senior analyst in county public works before she joined Koenig’s staff. Koenig said that made her well positioned for the role.

Koenig had been set to appoint Bud Colligan as his alternate. “He just decided that he could be more effective continuing to work independently,” Koenig said of Colligan, in an interview.

Related stories

- County land for temporary housing included in homeless proposal – March 6, 2021

- Potential new rules ahead for homeless camps in Santa Cruz – Feb. 24, 2021

- Tent camp could be removed at Highways 1 and 9 – Feb. 10, 2021

- Plan to tackle homeless advances in Santa Cruz County – Nov. 10, 2020

- Read more Santa Cruz Local stories on homelessness

Stephen Baxter is a co-founder and editor of Santa Cruz Local. He covers Santa Cruz County government.