Nearly half of Santa Cruz County residents live in unincorporated county areas such as Live Oak and Pleasure Point. (Kara Meyberg Guzman — Santa Cruz Local, flight courtesy of LightHawk)

SANTA CRUZ >> To fix crumbling county roads and address a $342 million repair backlog at county parks and facilities, Santa Cruz County supervisors are asking state legislators to change a decades-old property tax apportionment law.

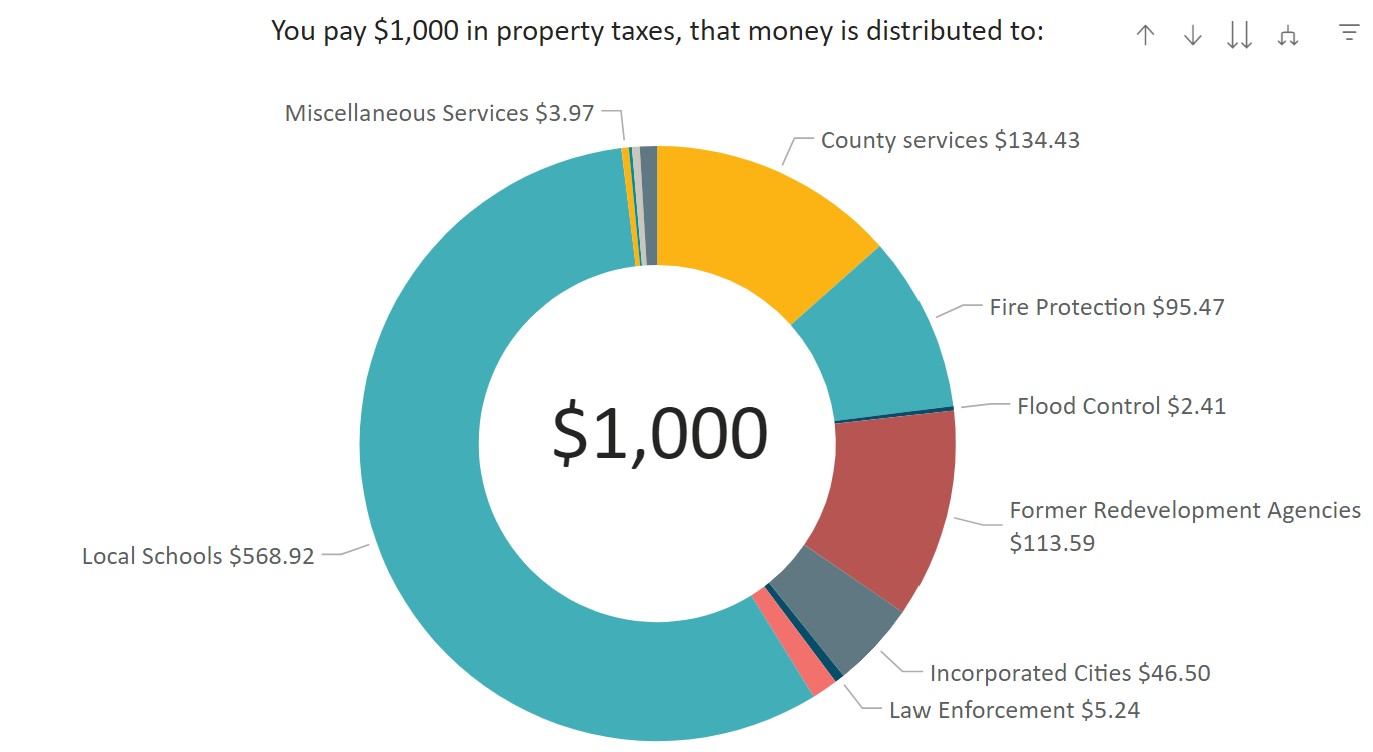

Nearly all property tax revenue collected in Santa Cruz County stays in the county, and it is split among school districts, the four cities, the County of Santa Cruz and special districts for services like libraries, water and fire protection.

- Santa Cruz County Supervisors Zach Friend and Manu Koenig said the problem is that the County of Santa Cruz gets 13.5% of property tax revenue because of an apportionment that was set in the late 1970s.

- That 13.5% is too low to adequately fund county services, the supervisors said, because about 49% of Santa Cruz County’s residents live in unincorporated areas outside of cities.

- The county is responsible for those roads, parks and other facilities. A lack of money has contributed to failing grades for county roads and millions of dollars in deferred maintenance at county parks and facilities, Koenig and Friend said.

“We have a lot of people in our community who are frustrated by their road conditions and a general lack of services while simultaneously paying a lot of money” in property taxes, Friend said in an interview. Many residents are “not feeling as though that money is being made available for core services,” Friend said, “and they’re correct because of this systemic issue.”

Friend represents District 2, which includes Aptos, Seacliff and other areas. Koenig serves District 1, which includes Live Oak, Pleasure Point and other areas.

On Oct. 17, the Santa Cruz County supervisors unanimously approved a resolution written by Friend and Koenig that requested state legislators to “do everything possible to change state property tax apportionment law.”

The resolution did not propose a new way to divide property taxes. Instead, it:

- Directed county staff to study possible alternative ways of dividing property taxes.

- Directed the board chair to reach out to other counties that may also be interested in reallocating property taxes.

- Requested that state representatives change the state property tax apportionment law.

The proposal has not yet been considered by state legislators, but it has brought attention to how property tax dollars are gathered and spent in Santa Cruz County and other counties.

Property tax background

In 1978, California voters adopted Proposition 13, which essentially limited increases to property taxes. Later that year and in 1979, the state legislature adopted related laws that froze the share of property tax money that groups receive within each county.

With a few exceptions, entities within each county still receive about the same share of property tax revenue as they did in the late 1970s.

Santa Cruz County’s property tax apportionment for Fiscal Year 2022-2023:

- School districts: 57.1%

- County government: 13.5%

- Cities: 4.6%

- County libraries: 1.4%

- Santa Cruz County Fire: 0.5%

- Other districts in the county: 22.9%

Back then, “Santa Cruz County was a thrifty county, meaning that we didn’t spend as much as some others might,” said Edith Driscoll, the auditor-controller of Santa Cruz County. She said state law essentially told local governments, “‘If you are a thrifty county and or a thrifty city, well, good for you. You’re going to be thrifty forever.’”

A County of Santa Cruz chart breaks down the distribution of each $1,000 paid in property taxes for a recent budget year. (County of Santa Cruz)

The county, cities and school districts also receive money from other sources, but property tax revenue is a significant part.

Koenig said the share of property taxes that the County of Santa Cruz receives is significantly lower than the state average for county governments. But comparing the property tax breakdown to other counties isn’t easy, said Driscoll.

Many county’s websites break down their property tax allocations. Few have the level of specificity needed for an accurate comparison with Santa Cruz County, Driscoll said. County staff are asking leaders of some other counties for more specific numbers. Driscoll said she plans to summarize how Santa Cruz County’s property tax funding levels compare with other counties by the end of the year.

“I fully expect that we’re going to be on the lower end, but it’s hard to know for sure,” Driscoll said.

Residents in unincorporated areas

Like every county, Santa Cruz County also is responsible for countywide programs such as health and mental health services, jails and the District Attorney’s Office and Sheriff’s Office.

The average California county has 43% of its residents in unincorporated areas. About 49% of Santa Cruz County residents live in unincorporated areas. Some counties that have a similar share of residents in unincorporated areas receive a greater share of the area’s property tax revenue.

In Santa Clara County, about 95% of the population lives in cities and 5% in unincorporated areas. “They can really devote money to their countywide programming, where we have to spend a lot of our costs covering people’s basic city-like services,” said Santa Cruz County Budget Manager Marcus Pimentel.

California counties on average receive $1,567 annually in property tax and sales tax per resident annually, according to the County of Santa Cruz. Santa Cruz County receives $552 annually in property tax and sales tax per resident.

Roads, county staff pay

The county maintains more than 600 miles of roads in mountainous and coastal areas that are prone to fire, floods and earthquakes. They frequently need repairs, and a lack of money for maintenance has made road conditions worse.

A bridge on Swanton Road at Mill Creek on the North Coast is damaged in the CZU Lightning Complex Fire in 2020. (Cal Fire)

Pavement conditions on Santa Cruz County-managed roads scored 48 out of 100 — significantly lower than the state average score of 65, according to a 2019 report. Santa Cruz County leaders would need to invest nearly $25 million annually just to keep that score, the report stated.

The county has spent closer to $5 million annually on county roads since 2019, Steve Wiesner, assistant director of public works, said at a recent Santa Cruz County Regional Transportation Commission meeting. County road conditions have deteriorated since 2019, he said, and that trend is expected to continue unless funding increases.

Friend wrote that the costs of deferred maintenance have piled up on county roads, parks and facilities.

Deferred maintenance as of fall 2023:

- County roads and culverts: Nearly $1 billion.

- County facilities including health centers: $131 million.

- County parks: $211 million.

The county’s adopted budget was $1.2 billion for Fiscal Year 2023-2024, according to county documents. Property taxes account for about 14% of budget revenue. Other sources include intergovernmental revenue and charges for services.

Santa Cruz County also struggles to pay competitive wages, Koenig said.

The Santa Cruz County Sheriff’s Office and the county’s Behavioral Health Division have not been fully staffed in recent years. Santa Cruz County is often outcompeted by Santa Clara County, which pays higher salaries for some of the same jobs, Koenig said.

School district money

Santa Cruz County supervisors haven’t said what groups would lose property tax dollars if more money was directed towards the county. School districts, which receive about 57% of property taxes in Santa Cruz County, could lose.

Koenig said that giving a smaller portion of property taxes to schools would not necessarily take money away from school districts. “If we shifted some of the property tax dollars around so that the county received a higher percentage, the state would basically contribute more towards our schools,” he said.

That’s because the state guarantees each school district a specific amount of money based on several factors including the number of students and the percentage of students from low-income families. If money from property taxes doesn’t reach the guaranteed amount, the state pays the remainder.

Former community college administrator Kathy Blackwood is skeptical that the state would agree to take over the funding. “You can’t just say, ‘Give me more money.’ You have to say where it’s going to come from,” Blackwood said. “You can’t ignore the fact that you’re taking money out of one pot. Something’s gotta give.”

In some school districts, property taxes bring in more than the state-guaranteed amount. In those districts, known as Basic Aid districts, the state gives a much lower amount of money, and school districts keep property tax money. If Basic Aid school districts lost property tax money, that could have major impacts, said Faris Sabbah, Santa Cruz County superintendent of schools.

If a new property tax formula allocated fewer property tax dollars to these districts, those funds could decrease or disappear, Sabbah said.

“It would have a major impact.” Schools might have to cut staff or programming, Sabbah said.

Santa Cruz County has three Basic Aid school districts:

- Santa Cruz City Elementary School District, which has four schools, received $9 million more than its state allocation in Fiscal Year 2021-2022.

- Bonny Doon Elementary School District, with one school, received $400,000 more.

- Happy Valley Elementary School District, with one school, received $139,000 more.

Koenig said any redistribution would be crafted to avoid removing overall funding from any district, including Basic Aid districts.

“Any politically viable solution would have to have zero or negligible impact on school funding,” he said. “After all, our schools are underfunded as well, and I think the last thing anyone wants is to take funding away from them.”

Another factor is that nearly 12% of Santa Cruz County’s property tax revenue goes to the state in the form of the Education Revenue Augmentation Fund, or ERAF.

The fund was created in 1992 to bolster state funding of school districts. Essentially, Santa Cruz County pays a portion of its property taxes to the state, and then receives some of that money back as state funding for schools.

Potential state legislation

Changing the way property taxes are divided would require a new state law.

The law “could simply change the formula for Santa Cruz County, it could allow Santa Cruz County to determine its own distribution formula, or it could change the distribution formulas for all the counties,” Koenig said.

Since 1979, few significant changes have been made to counties’ property tax allocations, but there is some precedent for adjusting the allocation through state law. In 1987, the California legislature enacted a law that guarantees cities a minimum share of property taxes. The law boosted the amount of property taxes received by many small cities, including Scotts Valley.

A similar law for counties could establish a minimum funding requirement for county governments, Driscoll said.

Pimentel, the county budget manager, acknowledged that changing the allocation of property tax money could be an uphill battle.

“These are tough situations, when you’re talking about reallocating the same pile of money,” Pimentel said. “Nothing’s easy, but when you start with a premise of equity and fairness, I think you can get people to listen.”

Read more

Questions or comments? Email [email protected]. Santa Cruz Local is supported by members, major donors, sponsors and grants for the general support of our newsroom. Our news judgments are made independently and not on the basis of donor support. Learn more about Santa Cruz Local and how we are funded.

Jesse Kathan is a staff reporter for Santa Cruz Local through the California Local News Fellowship. They hold a master's degree in science communications from UC Santa Cruz.