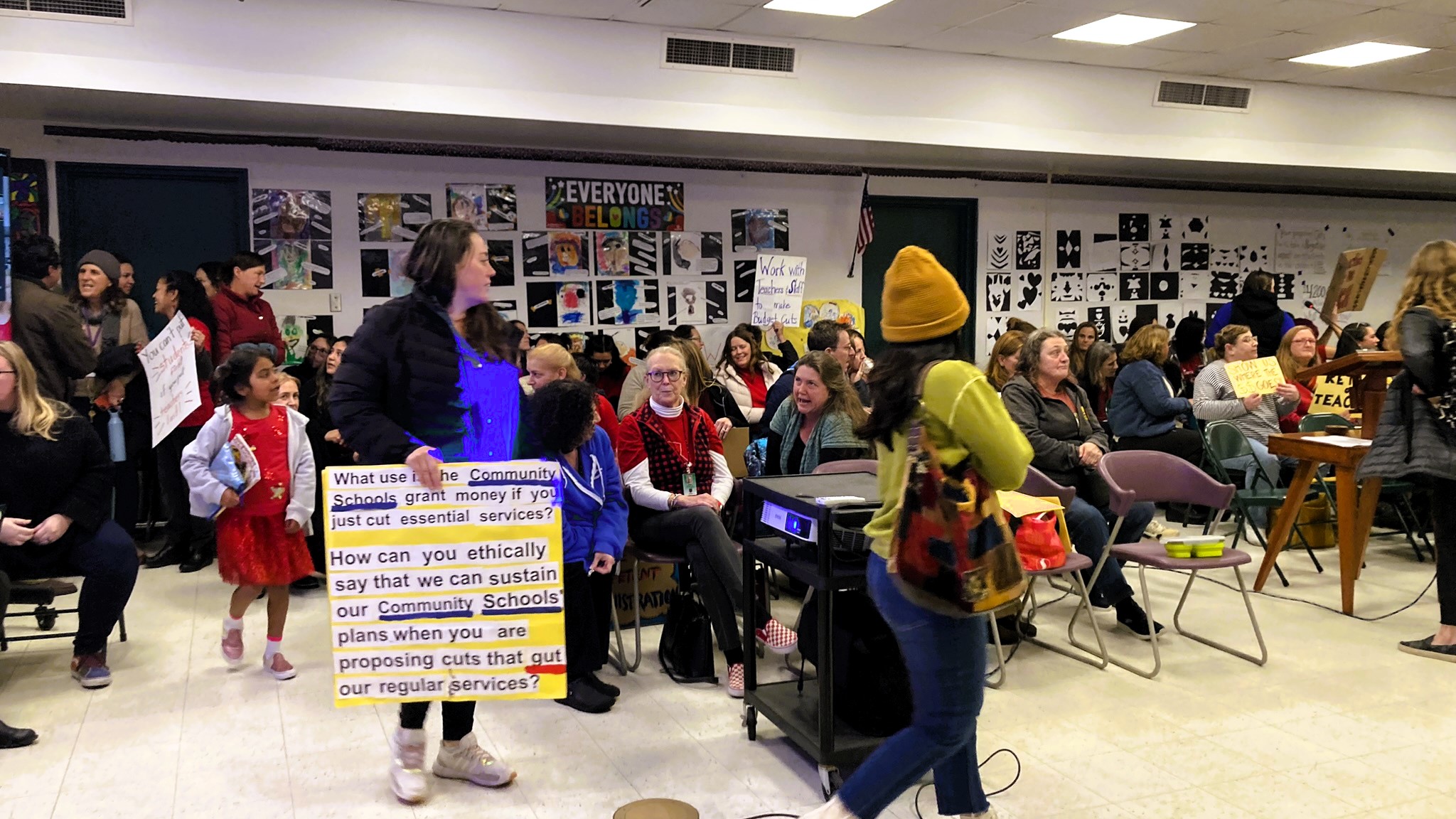

Parents, teachers and others pack the Green Acres Elementary School multi-purpose room during a Feb. 21 Live Oak School Board meeting. (Jesse Kathan — Santa Cruz Local file)

LIVE OAK >> In the wake of layoff notices for more than two dozen employees of Live Oak School District and the abrupt departures of its superintendent and two assistant superintendents, details emerged this week on where the district’s money went and how its management compares with other school districts in Santa Cruz County.

Jump to a section:

- Parents question outreach efforts

- New grants, programs and expenses at Live Oak School District since 2021

- Superintendent and administrator pay in Live Oak and other school districts

- Money reserves in Live Oak and other school districts

- Enrollment decline in Live Oak and other school districts

Live Oak School Board trustees this month approved layoffs to close a $2.9 million budget gap and avoid a potential state takeover of the school district. The district’s budget is about $28 million for the fiscal year that started in July.

Live Oak School District Superintendent Daisy Morales said she will resign June 30. Since she was hired in 2021, Morales championed programs to expand school services and promote deeper connections with the Live Oak community – especially Spanish-speaking parents. But those programs required more district staff and administrative spending, often fueled by one-time grants, district records show. Budget records show that over Morales’ tenure, overall administrative spending sharply increased.

Some parents have questioned whether Morales’ salary of $228,917 is proportionate to the pay of other school district superintendents in Santa Cruz County. Her pay is roughly in the middle of the county’s 10 school district superintendents.

At Live Oak and some other Santa Cruz County districts, enrollment has declined over the past decade, and absenteeism has jumped since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Fewer students in class has meant less state money for the school district. For years, the Live Oak School Board trustees have deliberately kept the district’s reserves close to its state-set minimum of 3% to pay for raises, school board members said. That strategy meant the district couldn’t weather another year of deficit spending.

Parents question outreach efforts

Yadira Flores has three children from first to fifth grade in Live Oak School District. She was excited when Morales was hired in 2021, and was initially optimistic about Morales’ efforts to boost connections with the Latino community.

Flores joined a group of Spanish-speaking parents who met every two weeks with Morales and community engagement staff. Together, they planned bilingual events like a welcome barbecue and El Día del Niño, Children’s Day. During a Feb. 20 meeting with Spanish-speaking parents, Morales told them budget cuts might be necessary because of decreased enrollment, Flores said.

Morales told parents that “our district is not the only one that is facing the enrollment concern,” Flores said. “This and that, but never the truth.”

Morales said in an email that she and a family engagement coordinator showed the same slide presentation as one shown during a Feb. 27 school board meeting, which included the district’s plan to address its money problems. “We spoke about the reason why we were in such a fiscal situation, declining enrollment being one of those issues,” Morales said. “We shared the full picture and all the proposed changes to services.”

Flores and Janeth Perez, another district parent, said Morales did share the presentation, but attendees weren’t able to fully understand it because it was in English.

Flores and Perez both said they didn’t know that teachers and aides were set to be laid off until after the Feb. 27 school board meeting. Parent Sandra Piedra said Morales spoke briefly about possible cuts, but did not detail potential positions that were slated for layoffs. Flores said Morales urged parents to attend the meeting and advocate for the importance of family engagement staff.

Morales said she and the engagement coordinator discussed “what services were on the layoff notices,” including math and reading aides, yard duty supervisors and family liaisons. She said that she encouraged attendees to speak up at the board meeting about “any positions they felt strongly about.”

Flores said she felt disappointed with outreach and wished family liaisons had told Spanish-speaking families about the budget crisis. It remains unclear who knew about the budget shortfall earlier this year. “This is supposed to be their job, to communicate with families what is happening, and none of them come to us with the truth,” Flores said. “We have to be finding out the truth through our white allies.”

Flores and another mom worked to translate school board documents for Spanish-speaking families, she said.

After the meeting, many of the parents in the group came together, Flores said. “We all said, ‘Wow, we feel used. We feel like they have been using us all this whole time,’” she said. Many, including Flores and Perez, agreed that they would rather keep staff that work directly with students, like teachers and aides, rather than family outreach staff.

Morales and family engagement staff made parents think they were forming deeper ties with the district “when they were really just using us,” Flores said. “It’s really sad, because they were speaking in the same language, and they were just using that as a convenient thing.”

Parents, teachers, staff and others attend a March 6 Live Oak School Board meeting at Live Oak Elementary School. (Jesse Kathan — Santa Cruz Local file)

New grants, programs and expenses at Live Oak School District since 2021

During Morales’ first school year in 2021-2022, she launched an effort to create “community schools” that expand services beyond instruction. The effort included new curriculums, expanded parent outreach and new programs to help struggling students.

Morales applied for state grants to pay for the programs, and received at least three, including $200,000 to create community schools and boost parent participation and $200,000 for anti-bias efforts.

The programs, and the grants that funded them, required more administrative staff.

The district hired more than a dozen new positions from 2021 to 2023, staff records show. Grant money, and one-time state and federal funds received at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, paid for some of the salaries, school board members have said. Those funds are running out, but most of the new positions are still on staff. Morales has said that she intentionally kept these positions for as long as possible.

“That choice, in some ways, has precipitated a situation now where they’re having to make those big cuts in a much more drastic” way, said Santa Cruz County Superintendent of Schools Faris Sabbah.

The district has applied for another state grant to continue the community schools program through 2029. Awardees are expected to be announced in May.

Using grant money “helps in the short term,” but “can create instability in the long term,” Sabbah said. Grantors usually require time-consuming reports as the money is spent, which can require more administrative staff, he said.

Many parents and staff have criticized the increase in office staff who don’t work directly with students. New full-time positions hired since 2021 include:

- A director of curriculum and instruction who chose new English and social studies curriculums. A fiscal stabilization plan approved March 6 calls for the position to be eliminated.

- A compliance coordinator to manage budgets and reports for federal and state grants.

- A director of fiscal services, who works under the assistant superintendent of fiscal services to coordinate the district’s budget, accounting and attendance.

- A human resources specialist who works under the assistant superintendent of human resources.

- Five family liaisons who connect with English- and Spanish-speaking families. Liaisons encourage family participation in school events, make home visits to discuss school-related issues like absenteeism, and translate for Spanish-speaking families at district meetings and events, according to a job description. The approved budget plan reduced the liaison positions to about half-time.

- A family and community engagement coordinator to manage the community schools program.

- A community schools coordinator to manage outreach efforts and the family liaisons.

In February, the Live Oak Elementary Teachers Association adopted a resolution of no confidence that stated that Morales has prioritized “new initiatives over crisis level needs while actively ignoring pleas from teachers, staff, and parents to focus attention on day-to-day operations.”

Other school districts in Santa Cruz County aren’t immune to the same financial challenges that Live Oak faces, Sabbah said. “Any one of our districts could be in a situation like this, I think that that’s part of the instability that comes with the way schools are funded,” he said. “I think part of our role is to be as protective as possible so that districts don’t find themselves in the situation that Live Oak is in at this point.”

But budget documents show that other districts, while facing similar challenges, have been more fiscally conservative than Live Oak School District.

Layoffs are expected at Live Oak School District to help cover a $2.9 million budget gap, school district leaders said. (Stephen Baxter — Santa Cruz Local)

A sign outside the Live Oak School District office offers enrollment for new students. (Stephen Baxter — Santa Cruz Local)

Superintendent and administrator pay in Live Oak and other school districts

Even before Morales started the community schools initiatives, Live Oak School District spent more on administration than the similarly-sized Soquel Union Elementary School District. Both school districts have about 1,600 students.

In Fiscal Year 2021-2022, Live Oak School District spent about 24% more on administrator salaries than Soquel Union, according to both districts’ School Accountability Report Cards.

Live Oak’s total administrative spending after Morales’ first year jumped from $2 million in Fiscal Year 2021-2022 to $2.6 million the following fiscal year, budget documents show.

In school board meetings, parents have questioned Morales’ salary compared with other superintendents’ salaries in Santa Cruz County. Morales is paid $228,917 in annual base pay excluding benefits. A 5% raise approved by the board in February and rescinded a week later would have increased her base pay to $240,363 annually.

Morales’ salary is higher than superintendent salaries at Santa Cruz County’s single-school districts and similar to superintendents’ salaries in districts with a similar number of schools. With the raise, her earnings would have been nearly on par with superintendents at the county’s largest districts — Santa Cruz City Schools and Pajaro Valley Unified School District.

There are 10 school districts in Santa Cruz County.

Money reserves in Live Oak and other school districts

Live Oak School District could have continued paying for more staff — at least temporarily — if it had higher reserves. But for more than a decade, the school board has kept the district’s reserves close to a state-required minimum of 3% of its budget.

In 2023, Live Oak School District increased its reserves to 9% of its budget. But some other districts in the county have built higher reserves in anticipation of the end of one-time funds and decreasing enrollment that means less state money.

For the 2023-2024 school year:

- Santa Cruz City Schools had 8% of its budget in reserves.

- Soquel Union had 16% of its budget in reserves.

- Scotts Valley Unified had 25% of its budget in reserves.

The Live Oak School Board deliberately kept its reserves low to pay for staff raises, Live Oak School Board Trustee Jeremy Ray said in a March school board meeting.

Enrollment decline in Live Oak and other school districts

Live Oak School Board Superintendent Daisy Morales has blamed part of the district’s budget crisis on declining enrollment.

Most school districts receive money from the state based on the number of students who attend school. Live Oak School District and some other Santa Cruz County school districts have had decreasing enrollment and increased absenteeism, which led to less money from the state.

From 2012 to 2022, enrollment has decreased by:

- 15% at Soquel Union Elementary School District.

- 20% at Live Oak School District.

- 27% at Santa Cruz City Elementary School District.

Families with children in these districts may be moving away because of rising housing costs, Sabbah said. As districts grow smaller, they may need to consider closing schools, he said. A single larger school has fewer administrators and lower building costs than two smaller schools, he said.

As enrollment has decreased in Live Oak schools, so has the average class size. Morales has argued that the district should reduce the number of teachers to bring class sizes closer to the upper limits in the district’s contract with the teachers union. As of 2021, class sizes at Live Oak are on par with those at Soquel Union, according to school records.

Since the onset of the pandemic, the percentage of enrolled students that habitually don’t attend school has increased. Other districts, including Soquel Union, are also struggling with chronic absenteeism.

Related stories

- Live Oak School Board approves layoffs in new plan – March 7, 2024

- Live Oak teacher layoffs proposed to avoid state takeover of school district — Feb. 23, 2024

- Live Oak Senior Center leaders seek space in teacher housing project — Jan. 30, 2023

Questions or comments? Email [email protected]. Santa Cruz Local is supported by members, major donors, sponsors and grants for the general support of our newsroom. Our news judgments are made independently and not on the basis of donor support. Learn more about Santa Cruz Local and how we are funded.

Jesse Kathan is a staff reporter for Santa Cruz Local through the California Local News Fellowship. They hold a master's degree in science communications from UC Santa Cruz.