The California Coastal Commission’s mission is to protect, restore and enhance coastal resources and public access to the coast, including Pleasure Point. (Kara Meyberg Guzman — Santa Cruz Local file, flight courtesy of LightHawk)

Last updated: May 18, 2023

Introduction >> The California Coastal Commission is a complex state agency with staff and commissioners up and down the coast charged with protecting California’s 1,100-mile coastline.

The commission defends public access to the beach, tries to limit greenhouse-gas emissions and other development impacts and considers climate change in decisions on what may be built on the coast. The commission is a state agency with some judicial powers. It is housed within the California Natural Resources Agency.

The commission also has final review of development, land use and laws in the Coastal Zone. The zone is 1.5 million acres and includes parts of Santa Cruz County and the rest of the state’s coast under the California Coastal Act.

Decisions on whether RVs can park overnight in the Coastal Zone, housing developments, repairs and improvements to West Cliff Drive and other proposals in the Coastal Zone are all examples of topical local issues the commission can weigh.

Despite having a small staff and being sued frequently, the commission often has limited coastal development and been an experiment in governance since its creation, sources said.

This Santa Cruz Local guide will explain how the commission works, how commissioners are appointed, how meetings operate, the process of coastal development permits and more.

—Michael Warren Mott

Purpose

The California Coastal Commission was established in 1972 by ballot initiative Proposition 20 and made permanent by the state legislature with adoption of a 1976 law called the California Coastal Act. With local governments, the commission regulates coastal development in California in the name of protection of public access and preservation of the coast.

Retired state Assemblymember Mark Stone said the commission has been a unique government body. Stone served on the coastal commission from 2009 to 2012.

“It’s a very, very unique animal, because it’s a state interest in the 1,100-plus miles of the coast within the boundaries of the Coastal Zone, but it is implemented on the local level,” he said.

Local governments across the state each create a Local Coastal Program, a plan that guides development along the coast. Each plan needs approval by the coastal commission. In areas that do not have a Local Coastal Program, the Coastal Act governs land use decisions.

Cities and counties occasionally update their Local Coastal Program. The Local Coastal Program, and any updates, are negotiated between the local jurisdiction and the commission.

“So then, the LCP [Local Coastal Program] is heavily influenced by the state interest, but implemented at the local level. I don’t think there’s any similar structure like that anywhere in the world. And it’s an interesting one,” Stone said. “It does give quite a bit of local control, but not completely because they have to be negotiated through the lens of the Coastal Act.”

The City of Santa Cruz’s Local Coastal Program was first approved in 1981. It was revised in 1992 as part of the city’s 2005 General Plan. The city’s Local Coastal Program was updated about 10 years ago. City leaders plan to present a revised Local Coastal Program to the commission in 2023, said Matthew VanHua, city principal planner.

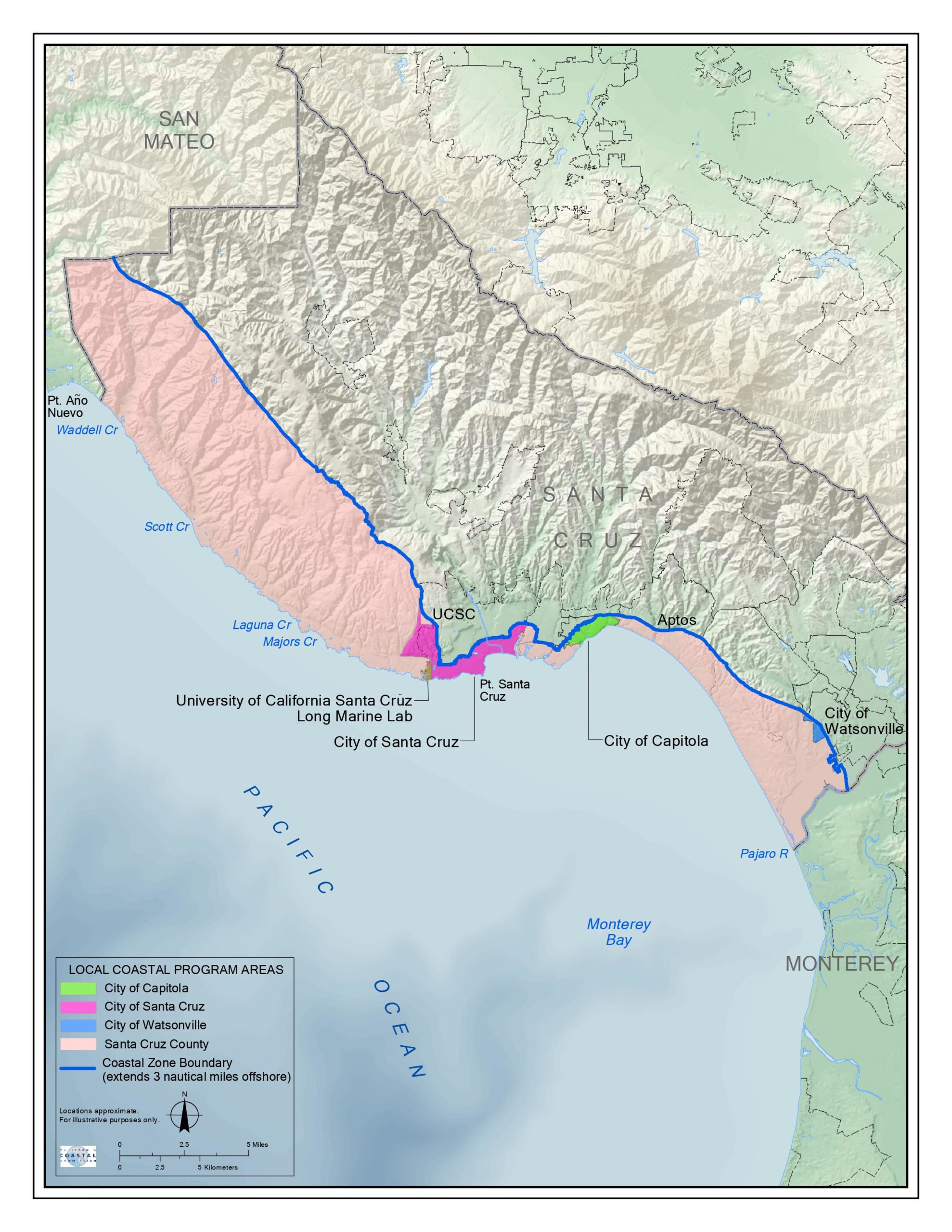

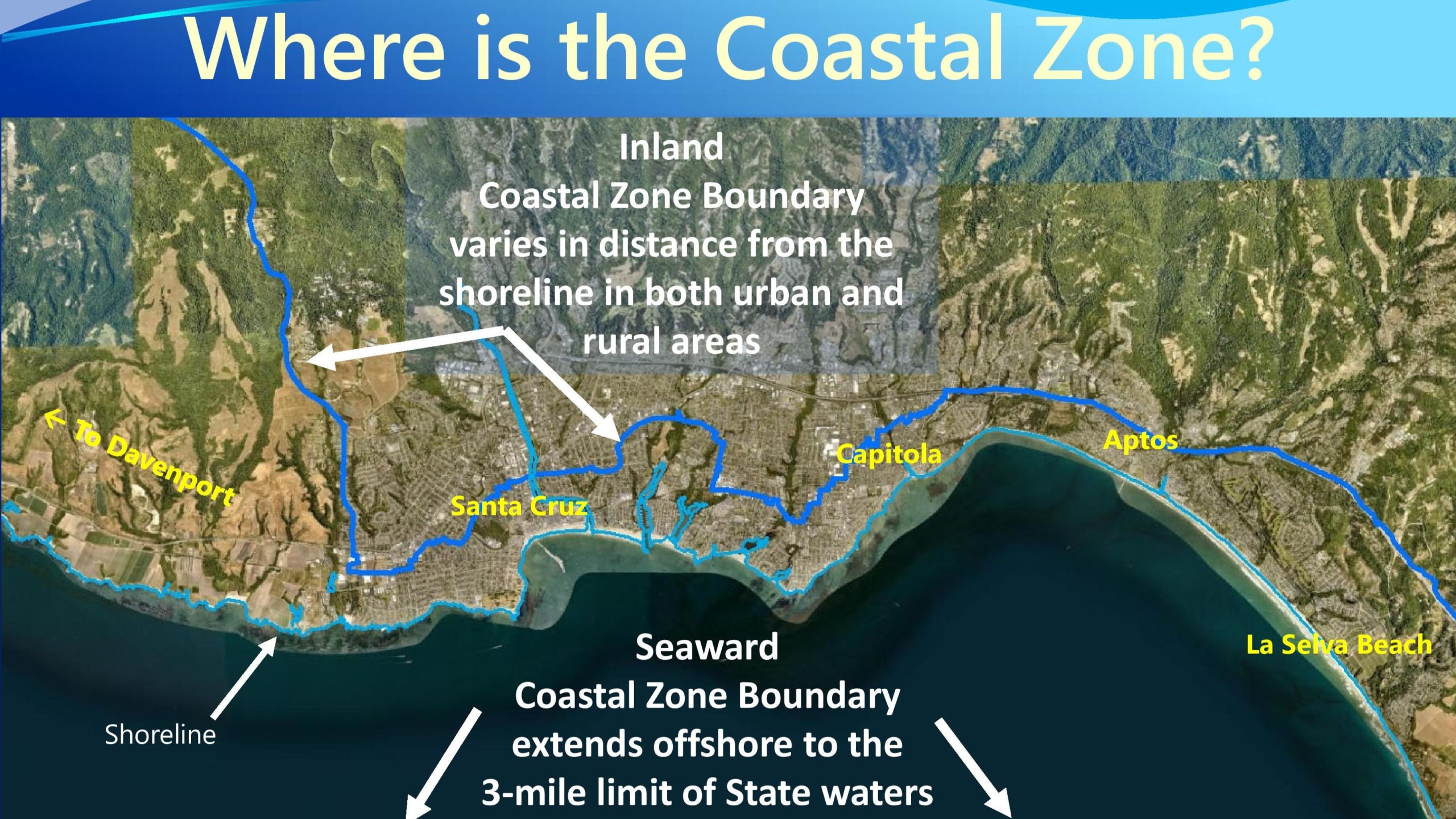

A blue line shows the Coastal Zone boundary in Santa Cruz County. (California Coastal Commission)

Across California, the Coastal Zone extends from the mean high tide line to either the first major ridge line in rural areas to about 1,000 yards inland in urban areas or the first major parallel road.

North of the City of Santa Cruz, the Coastal Zone can reach as far inland as five miles. Within the city, it follows West Cliff to the Boardwalk and covers many major residential and commercial areas including Downtown and the Eastside.

The Coastal Zone in the City of Santa Cruz extends roughly a half-mile inland. (California Coastal Commission)

“A third of the city is in the Coastal Zone, not just the immediate shoreline: several blocks inland and the southern part of Downtown Santa Cruz and Seabright area, all of the (Santa Cruz Beach) Boardwalk and beach area,” said Central Coast District Manager Kevin Kahn. “That’s not something people understand all the time; We’re not just talking about the city’s beaches, bluffs or West Cliff, though not everything raises a coastal resource issue.”

The Coastal Zone covers most of Capitola except for some areas near Highway 1. The zone hugs coastal areas south of Highway 1 through Aptos, Rio Del Mar and La Selva Beach to the county border. The small portion of Watsonville on the coastal side of Highway 1 falls within the zone.

”It goes bigger in rural areas and smaller in urban areas to protect more of the rural natural resources, wetlands, scenic views and agricultural land. The Coastal Act and how it’s been implemented by local government partners, Santa Cruz County and others on the North Coast, it’s not a coincidence – the Coastal Act and Local Coastal Program are a big reason why that area’s stayed rural and scenic,” Kahn said.

The Coastal Zone was negotiated and so is different for every jurisdiction, former commissioner Mark Stone said. He added that the commission has jurisdiction even over development inland of the Coastal Zone, if it touches or uses resources of the zone, such as large water treatment facilities.

To determine if your property is within the Coastal Zone, use the Santa Cruz County Planning Department’s website.

Commission members

The California Coastal Commission has 12 voting members, generally referred to as commissioners, as well as three non-voting members representing the California Natural Resources Agency, the California State Transportation Agency and the California State Lands Commission.

Santa Cruz County Supervisor Justin Cummings was appointed by State Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon to the commission to represent the Central Coast in March of 2023. His term ends in May of 2025.

As of May 18, 2023, the commission members are:

- Donne Brownsey, chair.

- Dayna Bochco, commissioner, public member.

- Caryl Hart, vice chair.

- Effie Turnbull-Sanders, commissioner.

- Ann Notthoff, commissioner.

- Linda Escalante, commissioner.

- Mike Wilson, commissioner representing Del Norte, Humboldt and Mendocino counties.

- Catherine (Katie) Rice, commissioner representing Sonoma, Marin, San Mateo and San Francisco counties.

- Paloma Aguirre, commissioner representing the San Diego coast.

- Meagan Harmon, commissioner representing parts of Santa Barbara, Ventura and Los Angeles counties.

- Roberto Uranga, commissioner representing Orange County and part of Los Angeles County.

- Justin Cummings, commissioner representing Santa Cruz, Monterey and San Luis Obispo counties.

Non-voting, “ex-officio” members:

- The Secretary of the California Natural Resources Agency: Wade Crowfoot.

- The Secretary of the California State Transportation Agency: Toks Omishakin.

- The Chairperson of the California State Lands Commission: Eleni Kounalakis.

Commissioners are elected officials or members of the public who are appointed by state governing bodies.

There are three appointing authorities — the governor, speaker of the assembly and the California Senate Rules Committee —and they each have four appointments. Two are elected officials and two are “public” appointments, who can be anyone, Stone said.

Each of the six California Coastal Commission districts has one locally-elected official appointed to the commission. Counties or cities nominate elected-official candidates. The appointing authority decides based on the nominations, said Charles Lester, former executive director of the commission.

For the six elected-official appointments, the governor makes the first in the northernmost district, followed by the California Senate Rules Committee, then the assembly speaker. The order repeats once more going south. The candidates typically sit on a city council or board of supervisors with land in the Coastal Zone.

The other six of the 12 voting members are “public members.” Public members are not required to have local government or land use experience. They may bring other experience in climate preservation or other work on the coast.

They could know the appointing authority personally, or have donated in prior campaigns, Stone said, or be environmental activists, for example.

He pointed to Ann Notthoff, a longtime advocate for environmental groups including the National Resources Defense Council who watched commission decisions for years.

“There’s somebody who’s being appointed as a public member who has never had local land use decision-making experience, but understands how those decisions get made and is very familiar with the Coastal Act and how it makes land use decisions,” he said. “So she’s somebody who was a very good appointment because of her familiarity with the subject matter.”

The Coastal Act states that the governor, the Senate Committee on Rules and the speaker of the assembly must “make good faith efforts to assure that their appointments, as a whole, reflect, to the greatest extent feasible, the economic, social, and geographic diversity of the state.”

Each commissioner may select an alternate, pending approval by the appointing government body.

Each voting member of the commission may appoint an alternate to serve in their place. The alternate must be confirmed by the commissioner’s appointing authority. Non-voting members may also have alternates.

Alternates will appear whenever the commissioner decides not to attend a meeting. Alternates are not always selected; sometimes the seats go unfilled.

Lester said, generally speaking, alternates reflect the main commissioner’s criteria or where they’re from, but not necessarily.

Stone said there can be a bit of politics when it comes to whom appointing authorities approve.

“When I was appointed, I was told, ‘Here’s somebody we would approve.’ So it wasn’t my choice. Fortunately, it was somebody I worked very well with and respected. It was a great choice,” he said. “I made a point to go to all the hearings, so she didn’t get to go very often.”

“You know they can’t technically say, this is your alternate,” he added. “But they can say, ‘Here’s somebody we would approve.’ ”

As of May 10, Commissioner Justin Cummings, the Central Coast representative and Santa Cruz County supervisor, said he had not selected an alternate.

“It’s vacant, but I just heard back from my top candidate, so it might not be for long,” he texted to Santa Cruz Local.

Most commissioners have four-year terms. Gubernatorial appointments serve two-year terms and are eligible for reappointment . Commissioners are appointed at various times; the roster of commissioners shows the dates of appointment and term expiration.

Commissioners’ terms are four years, and they cannot be removed until their term is up, except for gubernatorial appointments, Stone said, who can appoint and remove commissioners at will.

“Governors have done that, where they remove a commissioner for a hearing and then put them back in [afterwards] because of a particular decision that’s coming up that the governor wants to weigh in on,” Stone said. “So the gubernatorial appointments tend to have closer ties to the governor’s office than the legislative appointments.”

Meetings and process

Items come to the commission where the commission has original jurisdiction under the Coastal Act, such as large or offshore energy projects, projects over tidelands, submerged lands and public trust lands — or where there is no Local Coastal Program, and the commission acts like a planning body with the first and final say.

Where there is a Local Coastal Program, the commission then acts as an appeals body. While most governing bodies require a fee to appeal local land use decisions, there is generally no fee to appeal to the Coastal Commission. Stone said that leads to relatively more appeals to the commission.

Anyone who wants to appeal a development permit within the Coastal Zone first must go through the local appeals process before they submit an appeal to the coastal commission. For example, in 2019, residents filed a series of appeals to the Coastal Commission regarding a condominium project at 190 West Cliff Drive in Santa Cruz.

Appeals can be made on land use decisions and development within the Coastal Zone.

“Development is also very broadly defined and construed,” Stone said. “Whether you’re grading, moving dirt, taking out trees, anything can be development. It doesn’t have to actually be a building.”

Appeals may also relate to limitations on access, he added, such as city limits on parking on the coast, or whether people can have bonfires on the beach.

“That’s one of the key aspects to the Coastal Act, and hence the LCPs [Local Coastal Programs] – nothing shall prohibit access to the coasts,” he said.

The commission also reviews and acts on Long Range Development Plans of universities in the Coastal Zone, such as UC Santa Cruz — as well as port master plans in the industrial ports of Hueneme, Los Angeles, Long Beach and San Diego.

In addition, the commission reviews federal permits. While the U.S. government has superseding authority, Stone said they do negotiate with the commission.

Stone said commission staff tries to add items to the agenda quickly and in meetings close to the project site, but it’s tough to balance legal timelines for projects or appeals with the necessary research time for staff.

Charles Lester, former commission executive director from 2011 to 2016, said the agenda process is driven by the work priorities and statutory deadlines, with communication between all the district offices and headquarters.

“The commission historically has too much work and not enough staff, so they’re constantly triaging and prioritizing; so it comes from the bottom up, each district managing workload, items ready to be heard, agenda pieced together – and the final agenda set through headquarters office. Somehow it gets done every month,” Lester said.

He said when he was director, the process was fluid. After discussion with an applicant, commission staff may have more questions, and decide to delay the item. Postponements were frequent, Lester said.

“It’s an imprecise science and it is very human, you’re trying to coordinate a state’s worth of agenda items,” he said. “Some items take a whole day so you’ll need to move everything else accordingly.”

Central Coast District Manager Kevin Kahn said the process remained largely the same since 2016. Districts determine their part of the agenda based on when projects are ready for a hearing, working with the commission’s executive director in San Francisco.

“The commissioners themselves can of course check in with staff and see where in the process a particular project is, but staff is the ultimate one to determine whether something is filed and ready for a hearing,” Kahn said.

When an appeal is submitted to the coastal commission, the commission must first decide whether the appeal raises a “substantial issue.”

A substantial issue is essentially whether the appeal is worthy of investigation and the commission’s involvement. The commission considers the project’s impact on natural resources and public access as well as the project’s alignment with the Local Coastal Program and Coastal Act, among other factors. If the commission decides there is no substantial issue, the local jurisdiction’s decision stands.

If the commission determines the appeal raises a substantial issue, then the commission will review the project “de novo”. They take information from the local jurisdictions and make their own decision — rather than determine whether a lower court made a mistake like most other appeal bodies.

The commission gets sued — a lot, Stone said — so staff reviews are thorough and take a long time before they ever reach the commission.

“The commission wins most of its cases, because they get sued a lot and so their staff reports are very detailed, very accurate and very clear,” Stone said.

He added, “But because they’re understaffed, it takes a long time to get to the commission.”

Commissioners will usually not see an item until about two weeks before a decision, so the depth and thoroughness of staff reports is important, Stone said. They may have been briefed on it beforehand or taken a tour of the site in question.

The commission uses the Local Coastal Program as the lens for their decision – unless there is no Local Coastal Program at the local jurisdiction, then they use the Coastal Act. While other bodies like a city council or board of supervisors would consider factors such as financing, social issues and economic impact — the commission has a narrower scope: the Coastal Act and Local Coastal Program, Stone said.

Commission staff provides a recommendation, the commission hears from the applicant and appellant, then commissioners make a final decision — subject to court challenges, Stone said.

Lester said their decisions come down to evidence, public testimony and the law.

“They consider the staff report and the public comment and make decisions based on law and the facts,” Lester said.

Commissioners can also have “ex parte” conversations before a decision – meetings with interested parties outside of the public hearing. Ex parte conversations are either shared in the staff report or verbally at the meeting. Some commissioners don’t take them on principle.

“Then, people can see what information was flowing back and forth. However, they vary in their level of detail and that is the same when verbally shared at a meeting. Sometimes they describe at the hearing for many minutes or they just say they talked about ‘x.’ It can vary,” Lester said.

This 12-person body meets once a month for three days, changing locations monthly across the state.

Commission staff generally present information on many agenda items. Commissioners ask questions. Local experts often weigh in on geologic and ecological issues. Residents often have an opportunity to give comments.

Environmental groups or appellants will also share their thoughts, likely followed by the applicant and their lawyers or experts, said Stone. He added, having the meeting near the location of the project or appeal plays a big role in public access to the commission.

“One of the things the commission does, which I think is brilliant, is they have hearings up and down the state. None of the other statewide agencies do that. Anybody there will have an opportunity to hear that item and can go to the commission and speak, ” he said.

Rotating locations also means commissioners can take tours of projects that staff knows the commission will eventually consider. The tours include staff presentations and are also open to the public, Stone said.

After deliberation, a member of the commission will make a motion either following the staff report or not; it will be seconded and discussion will take place. Then eventually, after any proposed amendments, modifications or replacements – they vote.

Coastal commission meeting agendas, times, dates and locations are posted on the commission’s website in English and Spanish.

On the meeting agendas, under each item, there is a link to submit written comments.

On the top of the meeting agenda page, there is also a link to submit a request to speak.

After research and interviews with the permit applicant or appellant, commission staff makes a recommendation for the commission.

Lester, the former commission executive director, said in his experience, commissioners do tend to follow staff recommendations, but not always. In more controversial items, there are more questions, refinements and amendments.

“It can vary but to me, one of the most interesting and important parts of the Coastal Act and that process is that staff is given the authority and responsibility to come up with their best professional analysis and recommendation on how a project meets the law or not,” he said. “It’s one of the reasons why you have sometimes controversial power at the staff level — that gives you a lot of ability as an administrative body to bring forth analysis based again on your professional judgment on what you think the right thing is, not based on political direction.”

Lester added, commissioners also need to explain themselves if they vote in other ways than the staff recommendation.

“It puts the onus on the commission if they want to do something different to explain themselves and have a basis for that since the legal standard is still substantial evidence for decisions being made; so if they see things differently, they need to explain it, which is the other side of that transparency – it’s a good thing.”

Stone said most decisions are approved because of the long lead time with staff research and negotiation.

“Usually, I guess 95% of what gets presented to the commission they approve. And because most of it is highly worked out and negotiated, generally, they’re following the staff recommendation. Like any jurisdiction, if something is controversial, really high stakes, not necessarily,” he said.

“I’d say sometimes there’s some deference to a locally-appointed commissioner, say if an item concerns geography where the commissioner is from — but at the same time the commissioners can be very independent,” said Lester, the former commission executive director.

Former Commissioner Mark Stone said commissioners at least listen to the local representative’s view.

“They will appreciate it when a local elected with local knowledge weighs in. But does that decide the item? No. Does it influence, maybe? There’s some courtesy and respect around that. But it’s not ultimately going to be definitive,” Stone said. “It’s 12 very independently minded people. You don’t get to this level generally without having your own mind.”

Lester said sometimes, commissioners vote against the priorities of their local constituency.

For example, Lester said, in 2011, Stone voted against the proposed 125-room La Bahia Hotel in Santa Cruz. The Santa Cruz City Council had supported the project. The commission agreed with Stone and denied the project.

The commission has about 182 staff positions in seven offices across the state, said Sarah Christie via email, the commission’s legislative director.

In the local Central Coast District office at 725 Front St. in Santa Cruz, there are 11 staffers for the commission, including planners, supervisors, a director and a manager. The Central Coast District comprises the 300-mile coastline of Santa Cruz, Monterey and San Luis Obispo counties.

“We have a super small staff,” wrote Kevin Kahn, Central Coast District Manager in an email.

State Sen. Mark McGuire called for enhancing the commission staff in a May 11 commission meeting regarding expediting off-shore wind projects.

“I’m speechless and that doesn’t happen often,” replied Commission Chair Donne Brownsey. “That means a lot to us.”

Coastal development permits

“Development” is broadly defined in the Coastal Zone, and could include:

- Demolition, construction, replacement, or changes to a structure’s size.

- Grading, removal of, or placement of rock, soil, or other materials.

- Clearing of vegetation in sensitive habitats, or that provides habitats.

- Impeding access to the beach or public recreational trails.

- Altering property lines, like through adjusting lot lines or subdividing.

- Changing the intensity of land use, such as using a single-family home as a commercial wedding venue.

- Repair or maintenance activities that could result in environmental impacts.

If someone wants to pursue development in the Coastal Zone, and the local jurisdiction has a Local Coastal Program, then they must apply for a coastal development permit with the local jurisdiction, such as the City of Santa Cruz or the County of Santa Cruz.

The Local Coastal Program serves as the “General Plan” of development in the Coastal Zone for each local jurisdiction, said Central Coast District Manager Kevin Kahn.

If there is no Local Coastal Program for the proposed development site, or the project is in the ocean, then they must apply for a coastal development permit from the coastal commission.

Not all development requires a coastal development permit. These activities could include:

- Improvements to structures that do not pose an environmental risk and are not located in or near areas with sensitive coastal resources or between the shore and first public road.

- Replacement of most structures destroyed by disasters, provided certain criteria.

- Some repair and maintenance activities that don’t enlarge or replace structures, do not involve a big risk of negative environmental impact, and are not located in or near sensitive coastal areas.

- Some temporary events that meet requirements, such as less than a two-week duration, and no significant impacts to certain sensitive coastal resources, including public access.

The City of Santa Cruz issues coastal development permits through the city’s planning department, said Erika Smart, Santa Cruz’s communications manager.

Visit the County of Santa Cruz’s planning department page on Coastal Zone permits for information on local coastal development permits in unincorporated areas.

At the commission, hearing deadlines kick in for coastal development permit applications after staff has determined the proposal is ready for a hearing.

The process may involve multiple review cycles before the commission staff determines that the application is complete and ready for a hearing.

Lester said, the main thing to understand about coastal development permit timelines is that there are information requirements to consider a permit.

“Submitting an application doesn’t mean you’re ready to go to hearing; you’ve started the process on ‘if you have enough information available,’” he said. “Feedback loops happen where staff will say, ‘You’re near a wetland, you haven’t provided information about that – please provide information about that.”

At the commission, those reviews are in 30-day cycles, Lester said. Once the commission staff has enough information, they will add the application to a commission meeting agenda. That starts a 180-day deadline for the commission to consider the application. The deadline can be extended another 90 days with applicant approval under state law.

The process is similar at the local level, including visits to the site, receiving comments from other reviewing agencies and writing a staff report, per the Santa Cruz County Planning Department. The City of Santa Cruz also offers coastal development permits, Kahn said.

Anyone who wants to appeal a development permit within the Coastal Zone first must go through the local appeals process before they submit a form to the coastal commission. For example, in 2019, residents filed a series of appeals to the coastal commission regarding a proposed 89-unit condominium project at 190 West Cliff Drive in Santa Cruz.

If commission staff doesn’t find a substantial issue, the appeal is essentially rejected and the process ends. If there is a substantial issue, the coastal commission performs its review and decides whether to issue the permit.

If the coastal development permit is appealed to the local jurisdiction, the council or supervisors can modify or deny the permit, or reject the appeal. If the appeal is rejected by the local jurisdiction, an appeal can be filed to the commission.

Santa Cruz County issues

In 2019, the Santa Cruz City Council approved a proposal to build 89 condominiums to replace the Dream Inn parking lot on West Cliff Drive. Opponents of the project filed a series of appeals to the coastal commission. Nearly four years later, the coastal commission has not held a public hearing on the appeals.

Central Coast District Manager Kevin Kahn said the hearing was stalled due to the pandemic, retirements and changes in staffing, as well as new questions for staff brought up by the application.

“Both (the pandemic and staffing) contributed to why it’s taken awhile, but it also has generated a bunch of questions we need to spend some time to understand, about the relation between density bonus law and the Coastal Act and Local Coastal Program,” Kahn said. “It has taken time to understand the issues, the pluses and minuses and how can density bonus both provide for affordable housing and also coastal resource protections.

Kahn said in May 2023 that they hope to hold a hearing soon, within “the next couple months.”

“We hadn’t dealt with these issues before in a contentious project setting. We have a better grasp on the issues now – so between the complexity of the issues, density and staffing were all reasons for this but we do recognize it’s taken awhile.”

In 2019, then-Santa Cruz City Councilmember Justin Cummings voted in favor of the 190 West Cliff project. In 2022, during his campaign for county supervisor, Cummings said he voted for 190 West Cliff in part because he thought the city would get sued if the council denied the project. Cummings said he wanted to demand that the developer build more affordable housing.

“Alternatively, voting in favor of that project, it would then go to the coastal commission, and then the coastal commission would need to be the one who would weigh in to determine whether or not that project met all the requirements. And by doing so that took the burden of disputing that project off the city,” Cummings said in 2022.

Cummings is now the Central Coast representative on the coastal commission.

Read more:

Issues concerning the City of Santa Cruz at the commission include the May 11 hearing on the city’s RV parking law, as well as its Downtown Plan and housing element, said Central Coast District Manager Kevin Kahn.

“Those are the bigger ticket items that our office is working on right now,” Kahn said. “We have a good working relationship [with city staff], and it’s a complex balance between the city doing its thing with respect to a whole host of issues and a lot of city is in the Coastal Zone, everything development and land use has to be consistent with Coastal Act and LCP [Local Coastal Program].”

The repair for the City of Capitola’s wharf was approved for a redesign a year and a half ago. The permit has been approved, so the rebuild will be able to proceed, Kahn said.

Discussions on West Cliff Drive continue between the commission and City of Santa Cruz; whether that ends up going to the commission remains to be seen.

Read more:

- Future of West Cliff Drive explored by residents, city staff (April 28, 2023)

Questions or comments? Email [email protected]. Santa Cruz Local is supported by members, major donors, sponsors and grants for the general support of our newsroom. Our news judgments are made independently and not on the basis of donor support. Learn more about Santa Cruz Local and how we are funded.