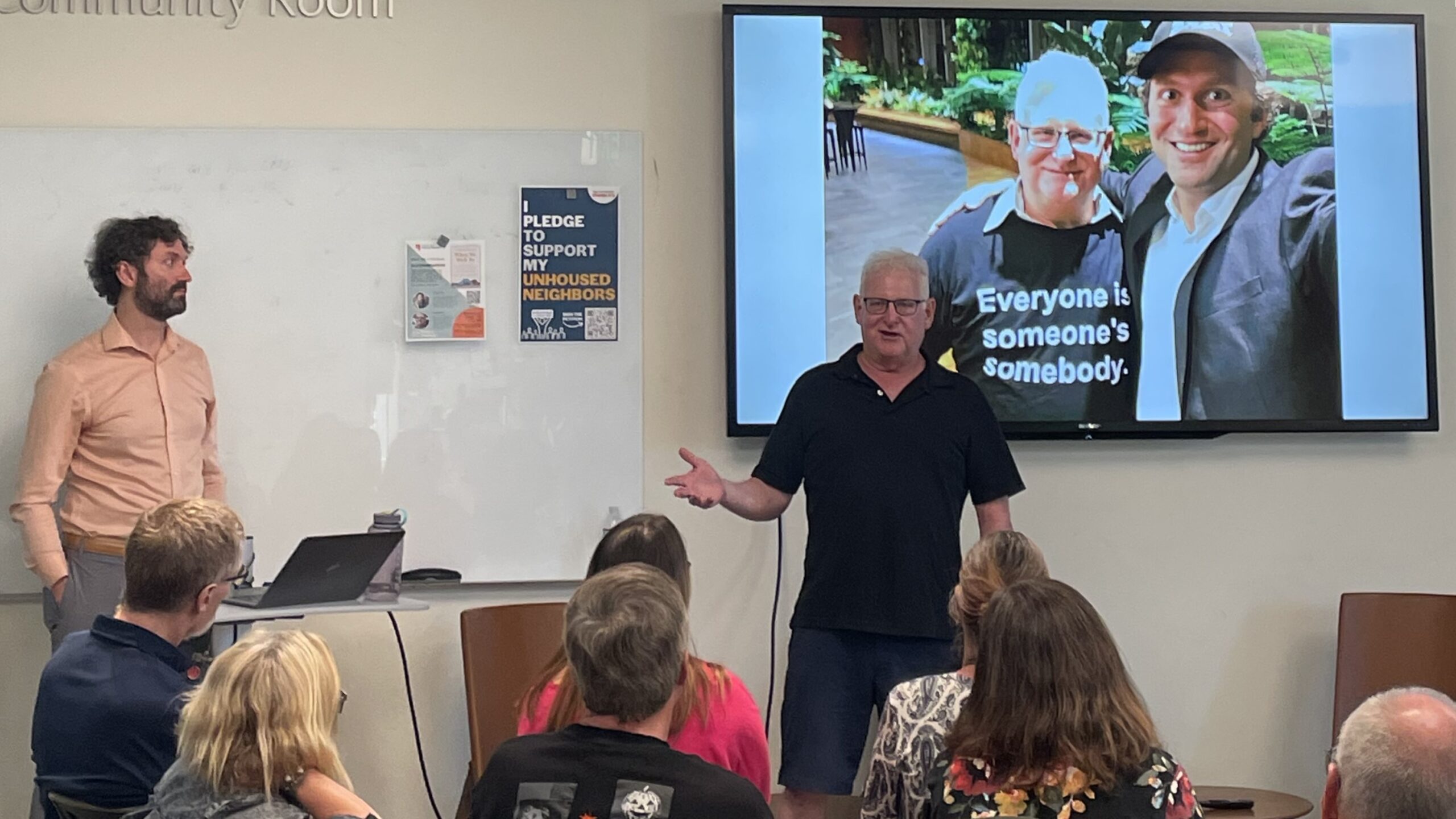

Author Kevin F. Adler, left, and UC Santa Cruz professor Chris Benner discuss how residents can support people who need housing. (Brianna Buda)

CAPITOLA >> While Kevin F. Adler was growing up in Livermore, his uncle Mark was homeless in Santa Cruz County.

Mark suffered from schizophrenia, and he lived on and off the streets for about 30 years. Despite his uncle’s circumstances, Adler said he sometimes took collect calls from Mark. Mark always remembered Adler’s birthday, and often sent him a gift in the mail. They saw each other on some holidays and shared meals.

“When we dropped him off in Santa Cruz at the Greyhound station or brought him back,” Adler said he wondered, “What was his life like? What did he see and how did the world see him?”

Mark died in 2004 at age 50, and he is now buried in Santa Cruz County. When Adler asked his father why he wanted Mark buried rather than cremated, he said it was because he wanted Mark to finally have “a permanent place to rest, just for himself.” In death, he got what he never had in life, Adler wrote.

After his uncle’s passing, Adler’s brain rattled with questions about his uncle and about unhoused people he saw every day in the Bay Area. He read widely, got in touch with leading researchers on homelessness and had countless conversations with people who needed housing.

He started to look at homelessness differently. He started to recognize how relationships and unrestricted money can lead many people to permanent housing. Even small amounts of universal basic income helped people eat meals regularly and secure a storage unit, for instance, reducing daily anxiety and allowing people to problem-solve other, less immediate issues.

On June 6, Adler discussed a book he recently co-authored, “When We Walk By,” with more than 25 residents at an event at Capitola Branch Library. The book addresses causes and solutions to homelessness, and offers a compassionate approach to homelessness at individual and policy levels.

Adler is also founder-in-residence of the San Francisco-based nonprofit Miracle Messages that facilitates reunions between houseless people and their friends and family. Adler’s book explores “relational poverty” as “a profound lack of nurturing relationships combined with stigma and often shame that makes fostering social ties incredibly difficult.”

Adler said, “Relational poverty as a form of poverty, it’s overlooked.” Improving social ties can improve health and be a primary tool for ending homelessness, he said.

Often internalized stigma associated with homelessness can be a contributor to the social isolation that houseless people deal with, and ends up being a barrier to their well-being, Adler said. One reason homeless people may choose not to reach out to their families is the stigmatization and “emotional burdens, self loathing, shame, fear, not wanting to be a burden,” Adler said. “And that’s, that’s heartbreaking. But it also, I think, opens the door to all of us being part of a better society around homelessness.”

More than 25 people attended a June 6 event at the Capitola Branch Library that explored some solutions to homelessness with “When We Walk By” co-author Kevin F. Adler. (Brianna Buda)

At the event, an unhoused woman named Erin spoke. She is temporarily living at the National Guard Armory near DeLaveaga Golf Course in Santa Cruz. She is part of Miracle Friends and participates in Miracle Messages, which connects homeless people with housed folks for regular 30-minute conversations.

Erin said she didn’t have family who were interested in connecting with her, and said that she often felt isolated as an unhoused person. “I’m just trying to get back up, and having the buddy system helps because there’s somebody you can talk to,” she said.

Erin shared stories about the kinds of traumas she experienced as a person living outside and advocated toward “anything that we can do together as a whole, to prevent it from happening to anybody else.”

Social isolation

During the Capitola event, Adler showed a photo of three people, two of them appearing unhoused and the third walking by without noticing them. Adler explained that this was part of a social experiment by the New York City Rescue Mission homeless services organization.

“They had individuals dress up to look homeless as unsuspecting members of their families walked by them and not a single person recognized their own son or daughter, brother, sister, husband or wife, or in this lady’s case — her mom and her dad,” Adler revealed to the surprised audience.

“Until we see people experiencing homelessness as people to be loved, not problems to be solved, the problem will never get better,” Adler said.

Author and nonprofit founder Kevin F. Adler, right, speaks to a resident at a June 6 event at Capitola Branch Library. (Tyler Maldonado — Santa Cruz Local)

Relationships and homelessness

Many Americans are a paycheck away from not being able to pay rent, Adler said. Many said they “don’t know where they’d get $400 for an unexpected emergency. It’s actually surprising we don’t have more homelessness.”

Adler said that different forms of “social capital” include friends and family, religious communities, and others are instrumental in keeping people off the streets. “What we’re finding is family, friends, relationships, social capital, could be peer-based, could be people who have that lived experience, whatever that type of experience is, that is making up the difference right now.”

Robert Ratner, director of Santa Cruz County’s Housing for Health Partnership, has said that internal conversations within the partnership are often aimed at this idea. The partnership coordinates homeless services programs in the county.

“We’re intentionally trying to convey that people often want to live together, and trying to get the entire community to think about people deciding who they want to live with and moving in together. So our housing efforts are really focused on helping people be with the people they want to be when they move in,” Ratner said.

Ratner said there was some pushback internally against this idea, however, since many in homeless services think that those relationships are part of the problem, not the solution.

“I think a lot of our service providers struggle with this because sometimes those relationships are actually perceived as and most outside observers would feel like they’re destructive.” Such considerations are factored in when, for instance, shelters refuse to disclose information about clients in consideration of some clients’ vulnerability to domestic violence.

Adler said during the meeting that such issues can often be resolved with “common sense” approaches, such as double opt-in provisions that prioritize agency rather than paternalism.

But Adler also said that it was also essential to understand the systems that produce homelessness, such as the criminal justice system, the housing economy, health care system, foster care system, and tax code, each one of which is analyzed in his book. He emphasized this by comparing the different rates of entering and leaving homelessness.

“For every one person that’s housed in San Francisco, another three become homeless. Right? So it’s an inflow problem as much as anything,” said Adler

Chris Benner, a UC Santa Cruz professor and author of the book Solidarity Economics, also spoke at the Capitola event. “What we need to be having conversations about is not just what do we need to do incrementally to deal with the symptoms of our problematic economy, but how do we understand the structures? And how do we change those structures?” Benner asked.

Money and messages

Adler’s nonprofit has facilitated more than 800 reunions between unhoused people and their loved ones, according to their website.

The nonprofit also connects housed volunteers to houseless conversation partners through its Miracle Friends program. So far, 34 Santa Cruz-based volunteers have volunteered 8,800 minutes of conversation time to homeless people throughout the country. Volunteers aren’t necessarily connected to unhoused people in their local communities, Adler said, with some volunteers from as far away as Bahrain offering to connect with unhoused people.

Miracle Messages is also piloting a program called Miracle Money that provides a universal basic income where the nonprofit facilitates direct cash transfers to some of its clients. It tested a pilot in 2021 and now administers a $2.1 million program funded by Google. Adler said preliminary results showed that recipients of the $750 monthly cash transfer were “two times more likely to exit homelessness versus the control group, and food security was significantly improved.”

Initially skeptical of how much change a few hundred dollars would make, Adler said Miracle Messages embraced universal basic income once they saw the initial results.

“Seeing our unhoused neighbors use the money in more resourceful ways than I could imagine for them — that was surprising, you know?” said Adler.

Adler said that while the numbers told a convincing story, the biggest challenge to overcome was the doubt that many still have about the ability of unhoused people to make proper spending decisions.

“What I think is being missed in that conversation is and most people still think this is a bad idea. And most people still think that unhoused neighbors are gonna blow it. There’s a narrative change that needs to happen,” Adler said, “and this takes time.”

Information about volunteering is at miraclemessages.org/getinvolved.

Questions or comments? Email [email protected]. Santa Cruz Local is supported by members, major donors, sponsors and grants for the general support of our newsroom. Our news judgments are made independently and not on the basis of donor support. Learn more about Santa Cruz Local and how we are funded.

Tyler Maldonado holds a degree in English from the University of California, Berkeley. He writes about housing, homelessness and the environment. He lives in Santa Cruz County.