A campaign finance allegation against Shebreh Kalantari-Johnson in the 2022 Santa Cruz County supervisors race remains unresolved in part because of the state’s case backlog. From left, Santa Cruz County Supervisor Justin Cummings, Ami Chen Mills and Kalantari-Johnson. Kalantari-Johnson is a Santa Cruz City Council member. (Photos by Devi Pride, Andrew Rogers and J. Guevara)

SANTA CRUZ >> More than one year after a campaign finance complaint was filed against former Santa Cruz County supervisor candidate Shebreh Kalantari-Johnson, the case remains unresolved among the California Fair Political Practices Commission’s backlog of more than 1,300 cases.

State leaders said they plan to add staff and enforcement efforts to reduce the case backlog and potentially accelerate investigations.

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s proposed 2023-2024 state budget included funding for 13 new Fair Political Practices Commission staff members, potentially including seven staff in the Enforcement Division, said FPPC representative Jay Wierenga. As of June 15, California lawmakers had not approved the budget for the fiscal year that starts July 1.

“The positions are what we asked for in the budget, but the positions themselves are subject to change based on circumstances and needs,” Wierenga wrote in an email.

The Enforcement Division has typically carried over about 1,450 cases each year since 2017. The Fair Political Practices Commission in January approved Enforcement Policy Directives aimed to reduce the backlog of open cases that has become “unacceptably long,” the directives document states.

The Fair Political Practices Commission is called upon to handle complaints of violations of state laws related to campaigns and campaign finance.

Santa Cruz County election case

In the June 2022 primary election for District 3 Santa Cruz County supervisor, Ami Chen Mills ran against Santa Cruz City Councilmember Shebreh Kalantari-Johnson and eventual winner Justin Cummings. Chen Mills alleged that Kalantari-Johnson and a group called Santa Cruz Together violated campaign expense reporting rules after a May 2, 2022 Santa Cruz Together event at Stockwell Cellars in Santa Cruz.

At the event, a Santa Cruz Together leader gave instructions to attendees on how to donate to help Santa Cruz Together’s efforts to elect Kalantari-Johnson, according to an audio recording.

Chen Mills first filed a complaint in May 2022 that was rejected by the FPPC that same month. She filed a second complaint in June 2022 that triggered an investigation that remains ongoing.

Kalantari-Johnson and Santa Cruz Together Chair Lynn Renshaw have said that they did not violate any rules of the Fair Political Practices Commission.

Wierenga, the Fair Political Practices Commission representative, declined to comment on the case this month.

Wierenga said that cases that involve a candidate’s possible “coordination” with a committee on an expenditure would likely qualify as a campaign “non-filer” case because “coordinated expenditures would give rise to filing and reporting issues.”

Campaign non-filer cases often take fewer than 100 days to resolve, but some enforcement attorneys at the commission say that cases that involve false reporting of coordinated activity as independent expenditures are more time consuming and difficult to resolve.

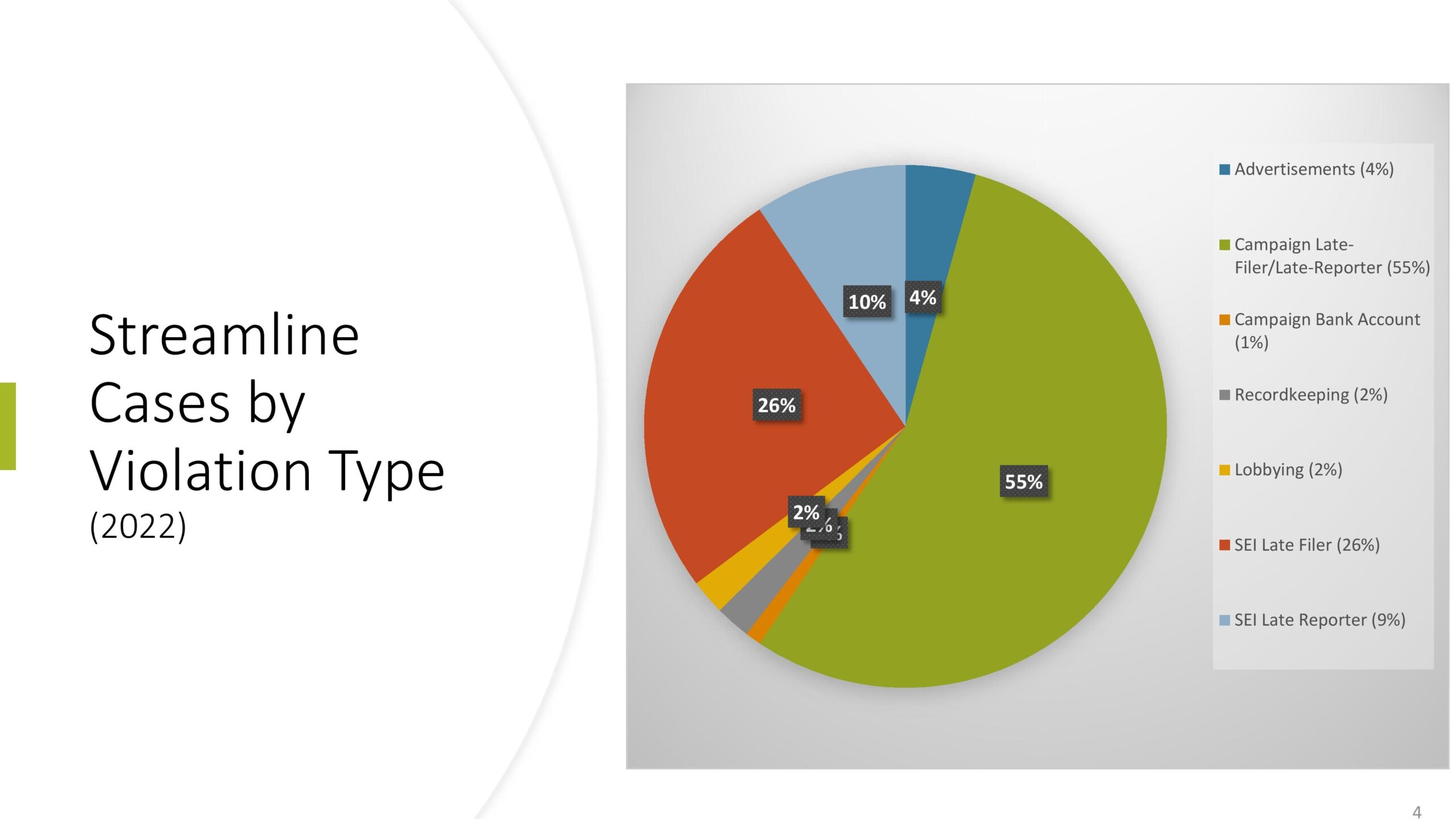

The largest share of “streamline” cases investigated by the Enforcement Division of the Fair Political Practices Commission involve late reporting of campaign finances. Other cases can relate to advertisements, record keeping and campaign bank accounts. (Fair Political Practices Commission)

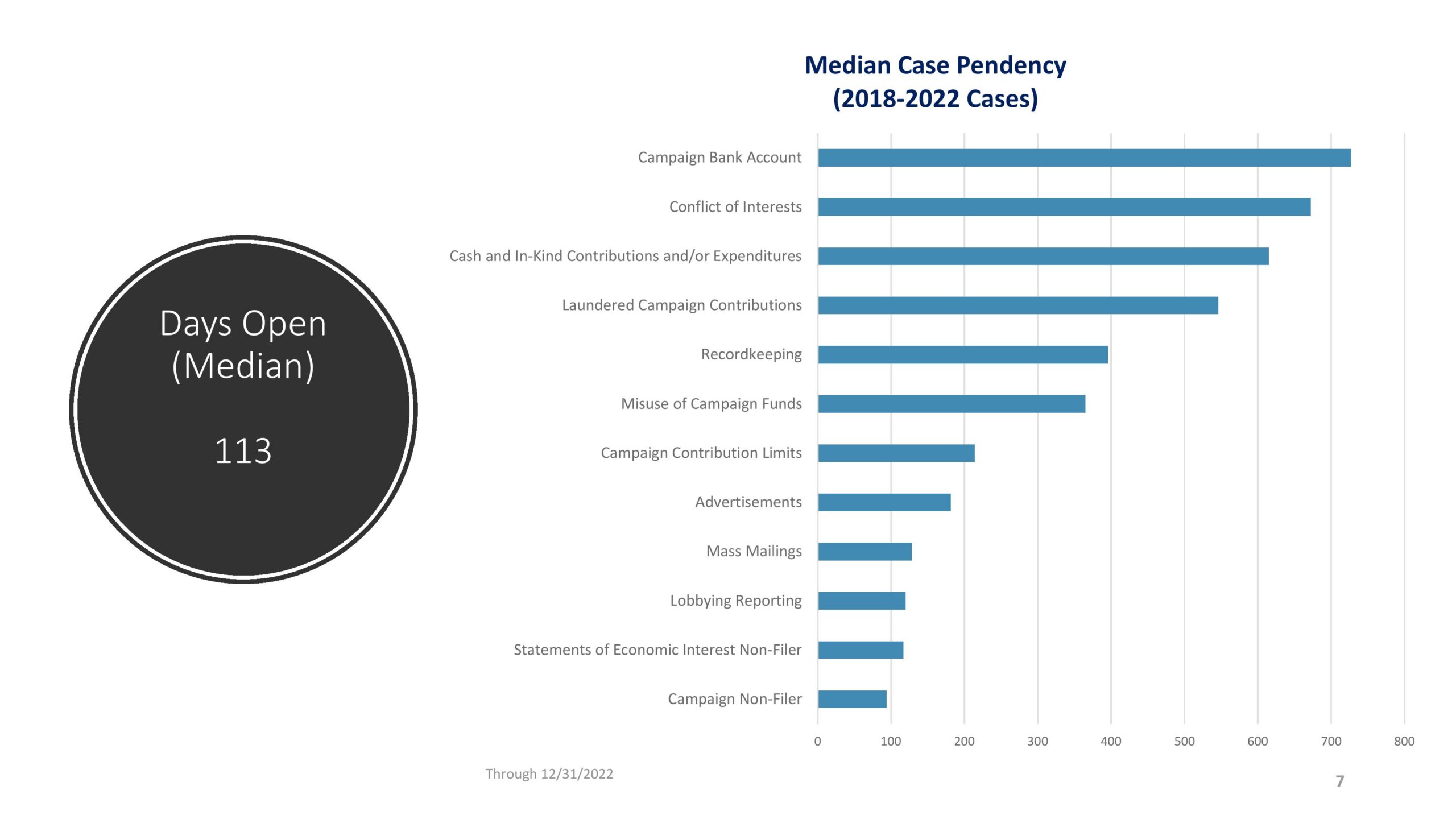

The median length of an investigation is 113 days, but some case types often take more than a year to resolve. (Fair Political Practices Commission)

A violation of California’s Political Reform Act can result in a penalty of up to $5,000 per violation. Minor violations can result in a warning letter. “Minor, technical” violations that are not a great harm to the public typically involve penalties of a few hundred dollars, Wierenga said in 2022. Factors to determine the penalty include harm to the public, intent and precedent, he said.

Kalantari-Johnson and Chen Mills said they have not received updates about the case from the FPPC.

“The wait has not impacted me personally or with my elected office work,” Kalantari-Johnson said this month. Kalantari-Johnson remains a Santa Cruz City Council member.

Chen Mills, who does not hold elected office, said the time it has taken to resolve the complaint indicates that “California is not taking electoral integrity seriously.” She said, “They must fully fund the FPPC so that they are robust and capable of handling such complaints in a timely manner.” Chen added, “It is info that voters should know before elections.”

Separate from the Santa Cruz case delay, leaders of the Fair Political Practices Commission made some recent changes to try to accelerate the pace of case resolution.

Fair Political Practices Commission changes

The Fair Practices Political Commission regulates and enforces campaign finance laws, lobbying activity, and conflicts of interest of government officials.

The commission includes a five-member board with a chairperson appointed by the governor and an executive director who oversees four divisions including the Enforcement Division. The division investigates cases and prosecutes violations.

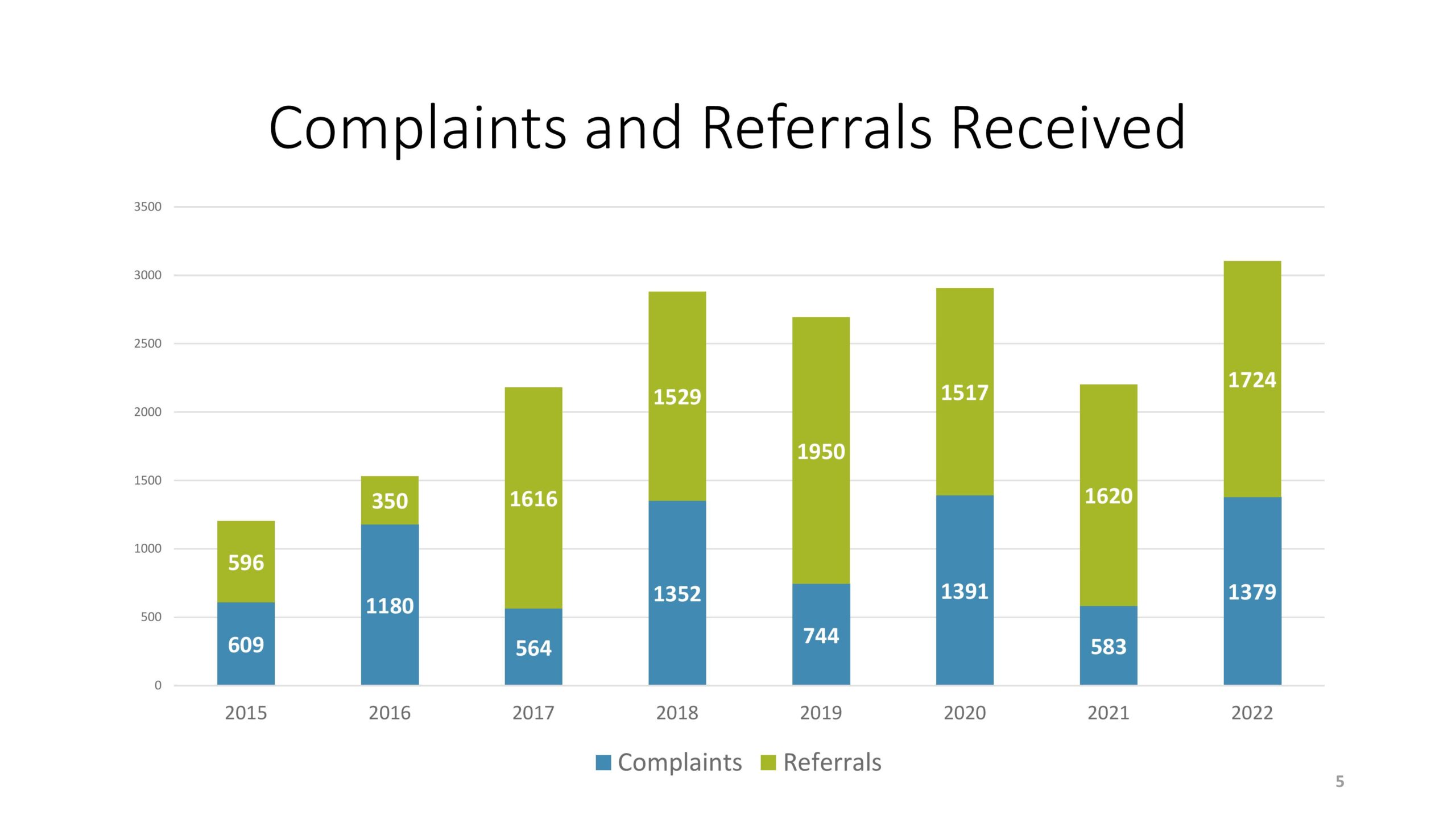

Complaints and referrals to the Fair Political Practices Commission have increased since 2015 in part because of increased public awareness and more knowledgeable filing officials with increased training, said FPPC representative Jay Wierenga. (Fair Political Practices Commission)

In 2022, the FPPC received more than 3,000 complaints and referrals, more than it had annually since at least 2015.

The median number of days it takes to resolve a case is 113 days, but it can range from single-day turnarounds to more than six years, according to a Fair Political Practices Commission document. The statute of limitations for potential violations of state campaign finance rules is five years, which can be paused.

Election-related cases are prioritized during an election “to the extent it’s possible to do so,” said Wierenga.

The case backlog and increased time to resolve cases is because of several factors, Fair Political Practices Commission Chair Richard Miadich said during a January commission meeting.

- More complaints and referrals to the division without a proportionate increase in staff.

- An absence of consistent standards, priorities, and deadlines across the Enforcement Division.

- Increased complexity of the law due to recent statutory changes.

In November, Miadich presented a proposal for new case completion goals, timelines and tracking.

Seven Fair Political Practices Commission attorneys wrote in opposition to Miadich’s proposal. In December, they wrote, “Under the current system of rules, without aggressive and decisive roll back of red tape, no amount of working hours — nor any policy requiring attorneys to touch a case every so many days — will resolve the backlog.”

Several Fair Political Practices Commission investigators wrote that they managed caseloads of 50 or more.

The attorneys recommended more authority to dismiss old cases with low public harm. They additionally expressed concern with the possibility of a deterioration in the quality of handling cases due to mandatory deadlines.

Reducing the case backlog

The Enforcement Policy Directives approved by the commission in January are similar to Miadich’s proposal in November. The Enforcement Policy Directives instruct FPPC leaders to reduce the current case backlog by 75% by the end of 2024 and ensure that the future annual carryover caseload does not exceed 625 open cases.

Reducing settlement offers and dropping charges in low-public-harm cases could help reduce the backlog, said FPPC Executive Director Galena West, during the January meeting.

“When you look at these older cases, and you think of them as sitting, that’s generally not what’s going on. They’re people that are not settling, and they’re not settling for a reason, and it’s usually money. So when we’re looking at these older cases and we want to get them resolved, and they’re lower harm cases that are just clogging up the works, then yes we’re going to have to use more discretion to make the best possible offer that we can in order for these cases to be resolved,” she said.

West added, “The public harm cases will not be compromised like that — the violations with the bags of money, the laundering, the things that the commission has identified as priorities.”

They were also directed to set deadlines for each task of every case to ensure that most cases are resolved within two years, and increase reporting of case needs, goals, and progress to the commission.

“The commission is not setting blanket deadlines for every single case. We’re not doing a one-size-fits-all approach; what we are doing is the common sense thing of requiring the Enforcement Chief communicate deadlines throughout the process appropriate to each individual case,” said Miadich, the Fair Political Practices Commission chair.

“I think it’s important that the commission express in clear terms to the enforcement division that most cases should be resolved within two years. We know that’s possible,” Miadich said.

Questions or comments? Email [email protected]. Santa Cruz Local is supported by members, major donors, sponsors and grants for the general support of our newsroom. Our news judgments are made independently and not on the basis of donor support. Learn more about Santa Cruz Local and how we are funded.

Tyler Maldonado holds a degree in English from the University of California, Berkeley. He writes about housing, homelessness and the environment. He lives in Santa Cruz County.