Santa Cruz County’s lockdown may last for months. We have to wait for one of three things: a vaccine, a treatment or herd immunity. A vaccine or treatment could take a year or more. Herd immunity — when enough people have recovered from the disease are now resistant — could also take a while. Local experts agree: A lockdown is needed to save our hospital system from being overwhelmed. But what if there’s another way? What can Santa Cruz County learn from countries that are suppressing the coronavirus without long, drastic lockdowns?

Our goal with our COVID-19 coverage: We want to connect you with information you need on the local response to COVID-19’s spread in Santa Cruz County. We also want to connect people in need with people and programs who can help.

We are not chasing breaking news. We’re examining solutions: what’s working elsewhere, how it might apply in our county, and where it might fall short.

We believe that a well-informed and supportive community will get us through this pandemic.

Here’s a list of questions that we’re using as a starting point for brainstorming our coronavirus stories, courtesy of the Solutions Journalism Network. Feel free to comment and share links.

We want to hear from you

What questions do you want answered? Take our short three-question survey. We’ll report back on our COVID-19 page.

TRANSCRIPT

Editor’s note: Our transcripts are usually only available to members. We offer our coronavirus-related podcast transcripts for free, as a public service.

Kara Meyberg Guzman: This episode is sponsored by Santa Cruz Works, your connection to our area’s thriving tech and business community. With over 5,000 members, Santa Cruz Works gives you access. The largest monthly tech events. Solutions for your startups and businesses. Connections to the hottest jobs. And the latest news about local companies: their stories, and best practices. Subscribe free to the Santa Cruz Works weekly newsletter today. santacruzworks.org/podcast

[MUSIC]

Stephen Baxter: I’m Stephen Baxter.

Kara Meyberg Guzman: And I’m Kara Meyberg Guzman.

SB: This is Santa Cruz Local.

[MUSIC FADE OUT]

This episode is about solutions. How can we get out of this coronavirus lockdown?

But before we do that, we have to understand the problem. Here’s Mimi Hall. She’s the Santa Cruz County Health Services Agency Director. She spoke at the board of supervisors meeting Tuesday.

MIMI HALL: There’s a huge demand for testing. And in an ideal world we would have broad availability of testing so that we could have the “n” number. We could understand, of all of those people that we’re testing, how many of them actually become positive. That gives us good epidemiological data. But we don’t have that capacity. So, from the very beginning of this, we have approached this as community spread.

Our testing capacity is ramping up but it’s still not enough to truly get what we need for the “n.” So it’s being limited right now to folks who are hospitalized, who are at high risk health care workers with known or potential exposure, because the utility of that is really important in terms of isolation or strategies.

For the general public, we are asking everybody: If you’re not symptomatic, testing is not of good utility. If you’re symptomatic and you have cold, cough, flu symptoms, we ask you to treat yourself as if you are COVID positive, or as if you have any other illness. And please stay home and self-isolate because you will overwhelm the system with testing.

SB: When Mimi talks about the “n”, she’s talking about the total number of people infected. We don’t have a good handle on who is infected, because we don’t have enough testing.

And they’re rationing tests for health care workers and people who have been hospitalized.

As of Tuesday, the county had received results from a total 178 COVID tests. Of those, 24 were positive.

That’s not very many tests. And that’s a big reason why we have a widespread lockdown. Everyone has to presume they have it. Everyone needs to limit contacts.

Local health experts agree: That’s exactly what we should be doing right now. It saves our health care system from being overloaded. And that’s critical.

But it comes at a cost. Businesses are shuttering. Kids are no longer in school. Our local economy is suffering.

And this may be just the start of our shelter-in-place order, according to a county epidemiologist.

We have to wait for one of three things to happen: either a vaccine, a treatment or herd immunity. A vaccine or treatment could take several months, maybe a year or more. Herd immunity — when enough people have recovered from the disease are now resistant — that could also take a while.

But if we lift the lockdown before then, the virus will spread quickly.

KMG: But what if there’s another way?

Can we ease this lockdown in a safe way?

Today we’re going to look at some potential solutions from elsewhere in the world. There’s a model that’s been used in South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore to suppress the spread of the coronavirus.

Leaders in the public health world are advocating for it. It’s not a perfect model, and it may not work for us, but we think you should know about it.

There’s three steps: Test. Trace. And quarantine.

Here’s Marm Kilpatrick. He’s a professor at UC Santa Cruz. He studies infectious diseases.

MARM KILPATRICK: The basic idea is to try to find out who’s infected, and then once we find out that a person’s infected we try to trace back and find out who they might already have infected, and test them as well. And then of course we try to get all these people that we now know are infected and have tested positive to isolate themselves and not contact any other people so they don’t lead to additional infection.

KMG: This isn’t anything new. It’s pretty basic. It’s what disease experts call “shoe leather epidemiology.” Other countries were able to do this because they had the testing capability. The US didn’t, and for a lot of reasons.

This model involves a team of investigators out in the field. They interview people. They review security camera footage. Basically they’re trying to find everyone who’s come in contact with those who have tested positive.

Countries like Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea have used this method to suppress the virus. They have not had to use long and drastic lockdowns. For sure, those countries have some movement restrictions, like travel bans. But in Singapore and Taiwan, for example, schools and workplaces are open. In South Korea, schools are closed but businesses are open.

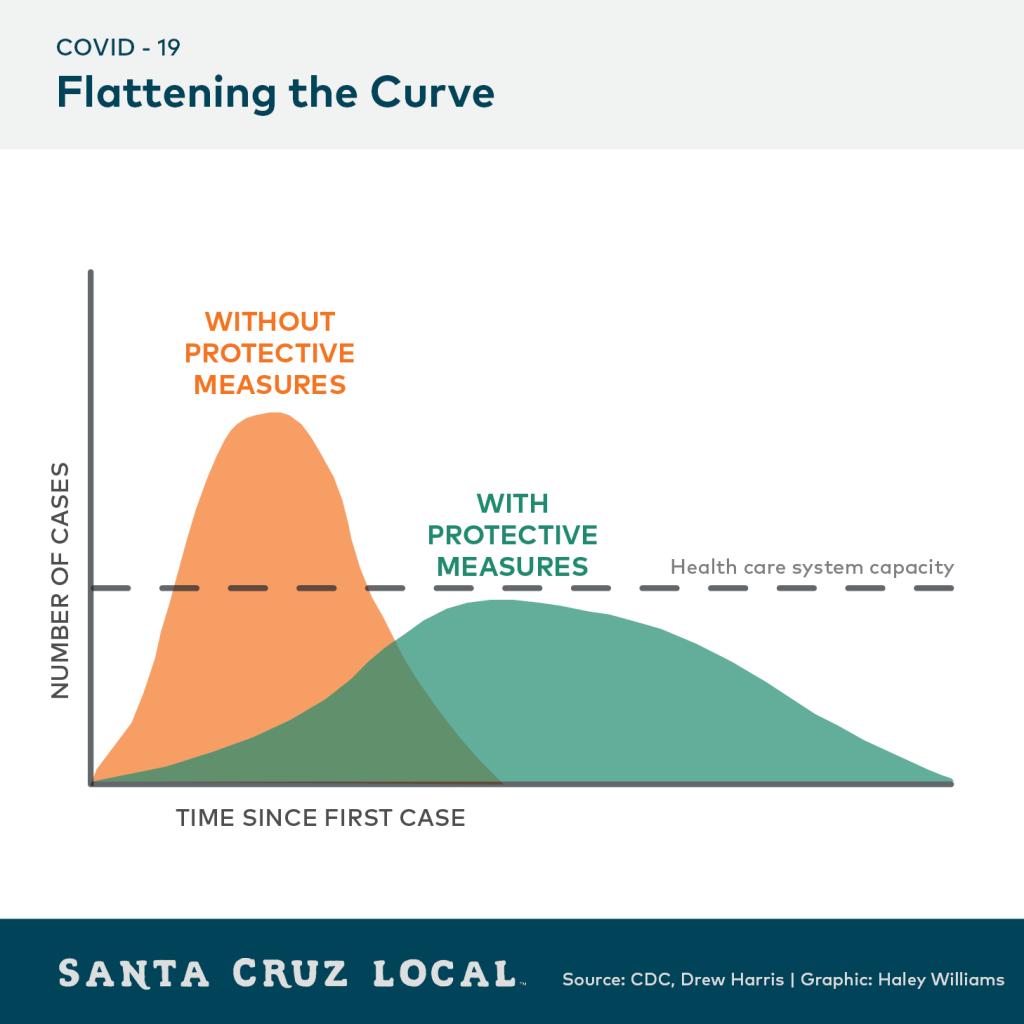

Of those three countries, South Korea has had the most successful response to the coronavirus. South Korea has flattened its curve of new infections. Singapore and Taiwan also have shown some success at limiting new cases.But they’re not finished yet.

Related stories:

- Singapore reports 73 new coronavirus cases in biggest daily jump (Reuters, March 25)

- Taiwan reports 23 new cases of coronavirus, total now 100 (U.S. News, March 18)

- Taiwan’s coronavirus cases top 200 for the first time (Reuters, March 23)

- Scientists warn we may need to live with social distancing for a year or more (Vox, March 17)

KMG: Santa Cruz County’s health department expects a spike in confirmed cases in the next three weeks. To ease the lockdown, the county would need to reduce its number of cases. That would make it easier to trace all recent contacts, Marm says.

MARM KILPATRICK: Before we can implement a strategy like this, we would actually need to reduce the cases down to a manageable number. So in Santa Cruz, that would probably be having a number of infected people in the tens, the kind of low tens, something like 20, 30 people, something like that.

We could conceivably test, find their contacts, find those that are infected, and get them to isolate.

KMG: There are at least four criteria for Santa Cruz County to try this model, Marm says. One, increased testing capacity. Two, have enough people power or technology to trace recent contacts. Three, you need a small caseload so you can track all those contacts. And four, you need the potentially infected people to cooperate with testing and quarantine.

This model probably would mean having lockdowns on and off as the virus spreads and recedes. That is, until we have widespread immunity.

MARM KILPATRICK: I think the best case scenario is for us to get to a place where we can basically be modulating our social distancing and our control efforts to where we can keep transmission at a kind of manageable level for both our healthcare system and minimizing kind of overall illness and death but also having as much of our normal societal processes as we can. And I think we’re probably going to have to modulate back and forth between more or less extremes of both of those as we figure out what we’re capable of doing and achieving.

And I should also say that’s also mixed in with, both the local processes and also between-location processes. So the extent to which people are traveling and moving around, that obviously makes it much more difficult to achieve kind of local control.

So I think there may be also be some kind of changes in movement. So as people may know, one of the first things China did quite early on, was reduce travel from the province where the outbreak was occurring to other provinces. And that enabled them to go to the other provinces and actually reduce transmission, when it was first getting started. So the province where it all started got hit really hard but most of the provinces in China saw much, much, much smaller epidemics because they greatly limited travel among provinces in China.

So I think you can imagine something similar happening, whether it’s interstate movement or within county movement or certain kinds of travel.Sso I think there’s some data suggesting that airplanes are obviously a relatively high-risk place to be for spreading respiratory infections, so if it means we reduce air travel for a while, those some of those kinds of things could basically help with some of the more local control strategies.

KMG: I ran this by Will Forest, the county epidemiologist we heard from last week. I asked him if he thought this test-trace-quarantine model could work here, in the county. That is, assuming we had the testing capacity and all the other criteria.

WILL FOREST: I think, I suppose yes, if you could test everybody today, and know who was infected and who was not, and you had the resources to isolate those people very thoroughly, and when you isolate someone and they get through it, then the virus in that person is dealt with and is out of our public system. And if you could identify and isolate effectively all of the infected people, yes.

But you see why I say that’s theoretically possible.

[DUCKS UNDER]

KMG: Will says the timing of testing is important. Everyone would have to get tested in a short period of time.

WILL FOREST: So even with the, I’ll call it the perfect situation that you’re sort of hypothesizing, even with that, you’ve still got to be able to do all the testing, very, very abruptly, sort of all at once, or you miss people.

If we’re really effective with the drastic measures that we’re taking right now, we should see the curve stop going up so steeply and have fewer new cases. And if you get few enough new cases, then I could imagine getting back into a situation where you could potentially do the legwork to trace those contacts and isolate everybody. But remember, in some places where they’re talking about that kind of thing, at least in China, I’m not sure about other places, they were taking measures far more stringent than what we’re doing here in California, where we’re saying don’t go to your job, stay in your house, you’re not allowed to have visitors. They were much more stringent than that in China.

KMG: So how do we increase our testing? Right now, we don’t have testing in the county. Samples are sent to Santa Clara County’s public health department and commercial labs.

One solution might come from UC Santa Cruz. The campus has several lab machines that could run viral tests. Those machines can run 100 samples every two hours or so. The campus also has robots that can assist with testing.

I contacted the campus’ associate vice chancellor for research. I asked him if the campus was planning anything.

He wrote to me that testing is among the ideas they are evaluating. They haven’t announced anything official.

Over the hill, Stanford faculty and alumni have formed a COVID-19 task force. They’re working on testing, prevention and treatment.

I heard about it from the owner of Spanner, a Santa Cruz engineering company. They’ve volunteered their services to the group.

[MUSIC]

KMG: Alright. Let’s assume for a second that our county could amass enough large-scale testing capacity. What about the next step? How do we trace all the recent contacts of infected people?

One solution could be a cell phone app. Some countries like South Korea and Israel, are using location trackers on cell phones to trace recent movements of people who have tested positive. Health officials can use that data to identify and warn people who may have been exposed to the virus.

In the U.S., government leaders are exploring similar uses of cell phone data.

Of course, there are privacy and ethical considerations. For example, the Chinese government is using an app to make automated decisions on quarantine. That probably wouldn’t fly in the U.S.

But there are advantages to automated data, said Marm Kilpatrick, the UCSC professor. Interviews aren’t perfect. For example, can you name 20 people you crossed paths with this last week? Even if you could, you wouldn’t know about the family that rode in the elevator, say, three minutes before you did, for example.

So maybe places like Santa Cruz County, that have limited staff and resources, could use tech to aid their response, Kilpatrick suggests. Or maybe harness the many smart and capable people who are right now sitting at home and want to help.

To get to these potential solutions, we need to deal with the reality on the ground.

The big question: Do we have enough hospital beds and ventilators? How ready are we to handle a surge of people who might need hospitalization in the next few weeks?

We have two hospitals in the county with intensive care units.

Watsonville Community Hospital has eight intensive care beds, out of a total 106 beds. The hospital has 15 ventilators. Six of those ventilators have limited capacity. Here’s Dan Brothman. He’s the chairman of the hospital’s board. I spoke with him by phone Tuesday.

DAN BROTHMAN: If the state comes up with ventilators we’ll absolutely take them and we’ll be able to equip more rooms then. But right now our, we feel the total number of ventilators that we have, the ones that can do everything and the others, we think we have a fairly sufficient number. But again, it just kind of depends on the number of patients. If we are inundated the way some of the hospitals in New York or the hospitals of Italy, nobody will have enough. So I just can’t really predict at this point in time.

KMG: Dan told me they’ll find some way to get more ventilators, if they need to. He also said the hospital can add to its 106 beds. Usually, around 60 of those beds are filled.

BROTHMAN: I don’t know that we’ll be able to get to 140. But we will certainly be able to —and you know, if the numbers grow we’ll put patients in non-patient room areas. We’ll keep people in the recovery room. We’ll do all kinds of things and we’ll get the numbers up. But, you know we are kind of a medium-sized rural hospital. You know, I think that when you’re in a big city, there are a lot more resources.

So we have limited resources. But we’ll use every space that we have in the hospital and we will utilize every person in the community that we can.

The ambulatory surgery centers have reached out to us and offered their assistance. As I said a pharmacist has reached out to us. And people who have retired have already contacted us. And, that’s what you do in an emergency.

KMG: Dominican Hospital, in Santa Cruz, also has an intensive care unit. The hospital’s capacity though is harder to pin down. The administrators wouldn’t give me numbers.

But a 2018 report I found said the hospital has 222 beds. Thirty of those were “special care” beds. That includes the intensive care unit.

Both hospitals right now have capacity for the current demand. Their emergency rooms are less busy than usual. People are staying away, unless they really need the help.

Both hospitals also have put up large tents in their emergency room parking lots. They screen people outside. And people with flu-like symptoms are treated in a different area.

But what about a few weeks from now? What’s the projected demand and can the hospitals rise to meet it?

If Santa Cruz County had no lockdown, then we could project about 13,000 hospital beds needed in the next 10 weeks. That’s a back-of-the-napkin calculation from Marm Kilpatrick, the UCSC professor. It’s based on hospitalization rates we’ve seen elsewhere.

Keep in mind — that 13,000 figure — that’s if we did nothing and went back to our normal lives.

But, of course, we are doing something. The statewide lockdown is decreasing transmission.

But we don’t know by how much, since we don’t have the testing.

[MUSIC]

SB: Here’s a few other things we learned in our reporting this week.

Like the rest of the state and nation, Santa Cruz County is burning through personal protective equipment like masks and gowns.

The county’s plan is to conserve gear.That’s according to Mimi Hall, she’s the county health services director. Health care workers and first responders get the gear first. Another way to conserve gear is to separate potential COVID patients from other patients. That’s the national guideline.

Leaders from Watsonville Community Hospital and Dominican Hospital seem to be preparing for a shortage of this gear. Leaders from both hospitals put out calls for donations of protective equipment. They need masks — specifically N-95 masks — gowns, gloves, goggles and hand sanitizer.

If you’d like to donate those to Watsonville hospital, call 831-763-6040.

If you’d like to donate to Dominican, call 831-462-7712. The hospital also has donation bins from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. near the main hospital entrance at 1555 Soquel Ave. in Santa Cruz.

We’ll put this information in the show notes and in the transcript.

SB : We want to hear from you. Tell us what questions you have about the local response to the coronavirus. Please fill out our survey. We’ve answered a lot of your questions on our COVID-19 resource page. That link is at santacruzlocal.org/covid-19.

You can leave us a voicemail. The number is 831-222-0460. We want to hear how you’re doing, your concerns, and any stories you want to share about how you’re coping.

Call us:

831-222-0460We will share some of those voicemails on our podcast.

SB: Sign up for our email newsletter. This week we’ve covered the Santa Cruz City Council and the county supervisors and their eviction moratoriums.

Times like these show the need for reliable local reporting. Our work is free, but we need your support. Please become a member and support our work. Membership sign up is at santacruzlocal.org/membership.

[MUSIC]

Thank you to our guardian level members: Chris Neklason, Patrick Reilly, Elizabeth and David Doolin, and the Kelley Family.

I’m Stephen Baxter

KMG: And I’m Kara Meyberg Guzman

SB: Thanks for listening to Santa Cruz Local.

Kara Meyberg Guzman is the CEO and co-founder of Santa Cruz Local. Prior to Santa Cruz Local, she served as the Santa Cruz Sentinel’s managing editor. She has a biology degree from Stanford University and lives in Santa Cruz.

Stephen Baxter is a co-founder and editor of Santa Cruz Local. He covers Santa Cruz County government.