Editor’s note: SB 50 had some major revisions in a committee hearing on April 24, after this episode aired. We’ve posted an update here.

Santa Cruz County’s history of no-growth policies have shaped today’s local housing crisis. Now, we’re at a crossroads with new state leadership that wants to spur development. We break down SB 50 — a proposed bill that would limit cities’ ability to block apartment projects. We tell you where in the county SB 50 would affect. We also tell you how local cities are doing with their housing goals (spoiler alert: not great). At the end, we talk about Santa Cruz’s pending Ross Camp closure and how to submit “audio letters to the editor.”

TRANSCRIPT

KARA MEYBERG GUZMAN: Welcome to Santa Cruz Local. I’m Kara Meyberg Guzman. Today we’re going to talk about housing. But first, let’s take a trip back in time.

[INTRO MUSIC STOPS SUDDENLY, RECORD SCREECH]

Santa Cruz in the 1970s.

[FUNKY 1970S DISCO MUSIC PLAYS]

Housing development was booming. Three-bed, two-bath ranch houses were sprouting up, from Scotts Valley, to Santa Cruz, to Watsonville.

Over the hill, Silicon Valley, the great economic engine, was being born.

UC Santa Cruz was growing steadily.

Santa Cruz County became one of the fastest growing counties in the nation.

And along with the people, came traffic, housing costs and sprawl.

But then, lawmakers wanted to hit the brakes.

[MUSIC STOPS, SCREECH]

In part because of a growing environmental movement, Santa Cruz County lawmakers started to limit growth. Developers’ plans for new suburbs were shot down. A nuclear power plant had been proposed for sleepy Davenport. But it didn’t happen. A convention center and condo project planned on Lighthouse Field was blocked after some residents organized in opposition. Then in 1978, county voters approved ballot Measure J, which put limits on how fast the county could grow. Some would say it succeeded, because it stopped Santa Cruz from becoming another San Jose or Orange County.

Fast forward to 2019.

The population has risen from about 188,000 in 1980 to about 274,000 last year. UC Santa Cruz has grown and plans to add thousands of more students in the coming years. But the county’s housing stock has not grown substantially. In part because of limited supply, the cost of renting a room in a house and the cost of buying a home has become out of reach for many people.

Now we’re at a crossroads. This year, our state got a new governor in Gavin Newsom. And there’s a state assembly that seems primed to tackle the state’s housing shortage and create some laws that make building easier.

Enter Scott Wiener.

[SOUND OF WIENER GREETING PEOPLE]

Wiener is a state senator from San Francisco. On a recent Friday he drove down from the city after a long work week to meet with Santa Cruz residents at Peace United Church of Christ on High Street. It was part of a statewide tour to talk to people about housing, and help drum up support for his housing bill, SB 50.

Basically, SB 50 would make it easier to build housing near public transit and job centers. But it would take away cities’ control in limiting growth — and that rubs many people the wrong way.

But here’s Wiener’s pitch. He wants to flip zoning on its head. Right now, most of the state is zoned ONLY for single family homes. That’s like your standard three-bed two-bath house. His bill would allow for more dense housing — like condos, townhomes or apartments — to be built in areas where there are public transit lines and job centers. That would open up lots of new housing to be built where only single family homes could be built before.

Here’s how he describes it.

SENATOR SCOTT WIENER: So when you think about affordable housing, housing that’s subsidized for low income people, say that a nonprofit developer builds, it’s all multi-unit, right?

KMG: Yep. Right.

WIENER: You’re not building single family homes that are subsidized for low income people. We would never do that. Or it only pencils if you do multi-unit.

So all these vast parcels in Santa Cruz, in San Francisco and everywhere else, where it’s only legal to build single family, that is off limits to affordable housing, right?

So SB 50 would take a whole bunch of those parcels and say, we’re also going to allow you to build multi-unit there. And so therefore, a nonprofit developer could build affordable housing there.

So the pool of eligible parcels for affordable housing will grow significantly under SB 50.

The bill is expected to be voted on by the State Senate Governance and Finance Committee on April 23rd, so it’s far from becoming law. But it’s worth talking about because it’s a potential way to help solve the state’s housing problem.

The upshot is that it allows more multi-family homes – like condos and apartments — to be built near busy bus stops, offices and shops. It’s about density vs. sprawl. Part of the thinking is, if people can live near their work and public transit, it helps reduce traffic and commute times. The bill represents a more urban vision for California.

And it works like this. I’ll only mention the parts that apply to us in Santa Cruz County.

Under the bill, local governments would have to allow apartments in single family zones, if the project is either near jobs or busy bus stops. In these areas near jobs and busy bus stops, the bill would also ease parking requirements, which have been known to kill projects.

Projects would have to meet a list of criteria, including local height requirements. So you don’t have to worry about five-story buildings suddenly popping up next door. That is, unless you already live in an area where five stories are allowed.

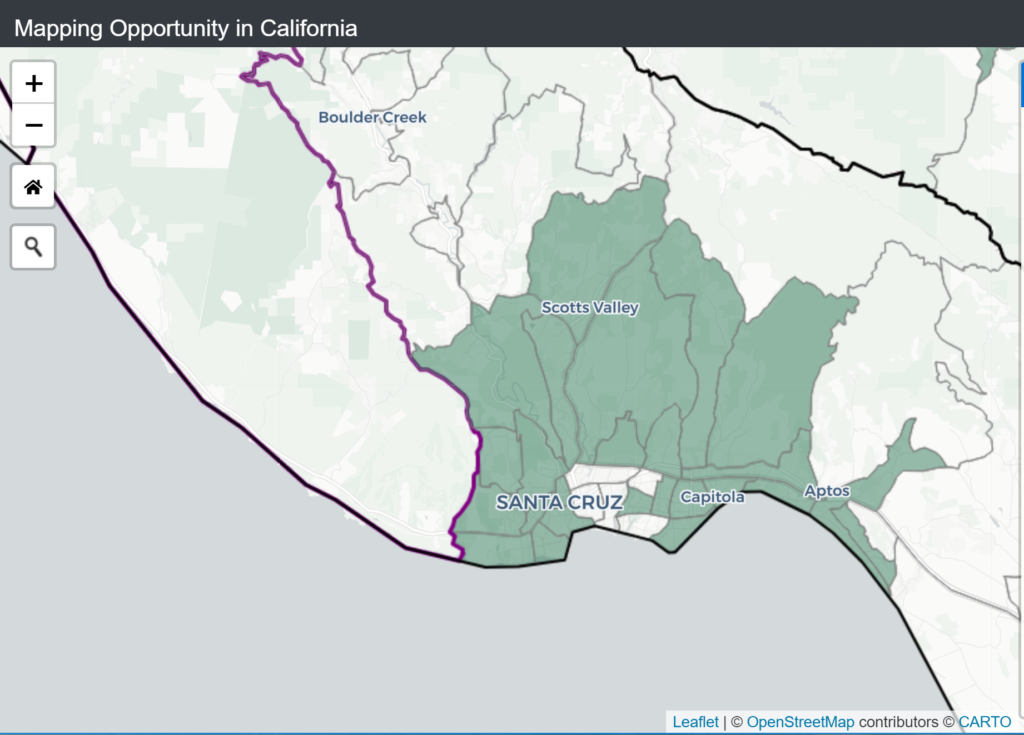

So, where are these areas in Santa Cruz County, that have lots of jobs or busy bus stops, where we may see more development?

Let’s talk first about where the jobs are. Basically, it’s most of North County: Santa Cruz’s downtown and Westside, Scotts Valley, Capitola, Aptos and parts of Live Oak.

http://mappingopportunityca.org/# and select ”

High-Opportunity, Jobs Rich, Long In Commutes, and or Jobs-Housing Mismatch.”

That’s according to a map released by The California Housing Partnership and three centers at UC Berkeley: The Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, The Urban Displacement Project and the Terner Center for Housing Innovation. We posted links and a map on our website, santacruzlocal DOT org.

A staffer in Senator Wiener’s office told me that they’re using that map as a starting point, but it’s ultimately up to the state to decide, should the bill pass.

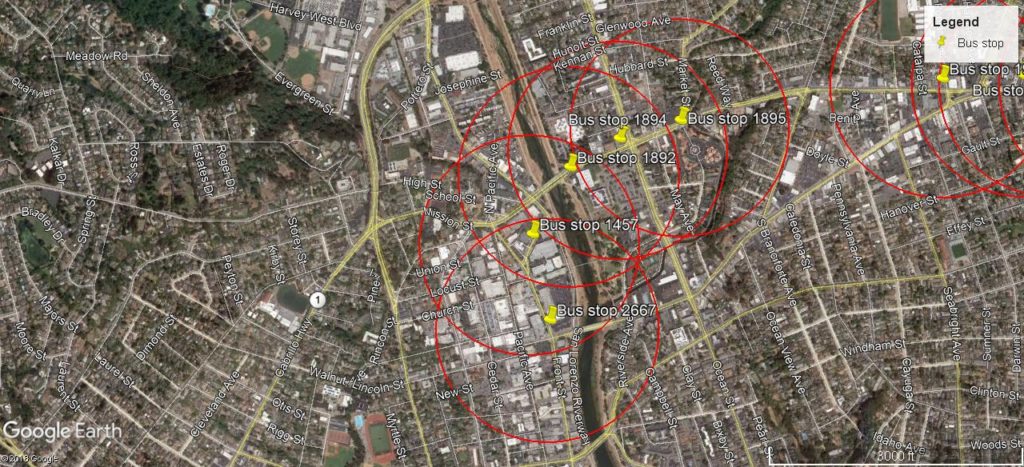

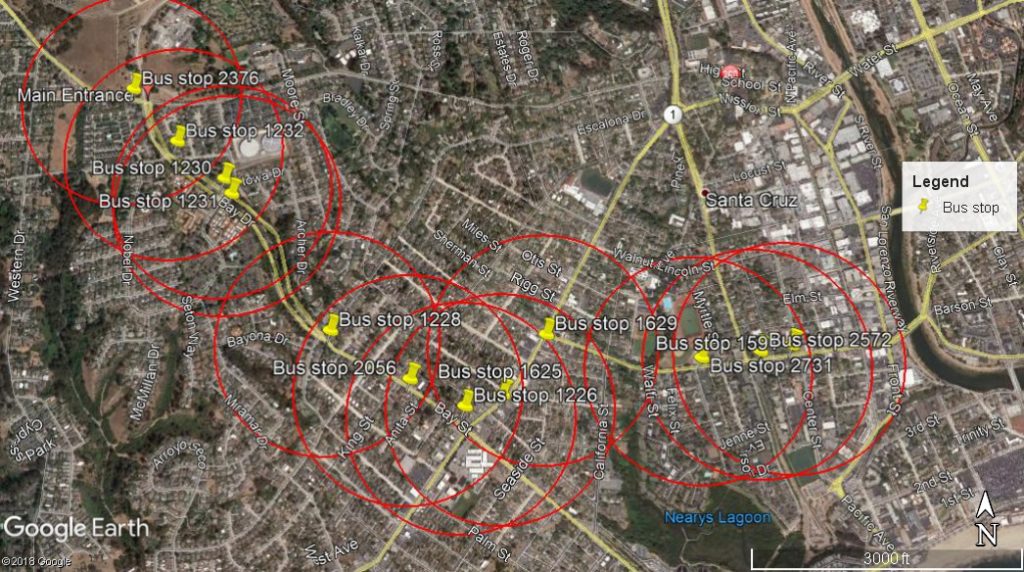

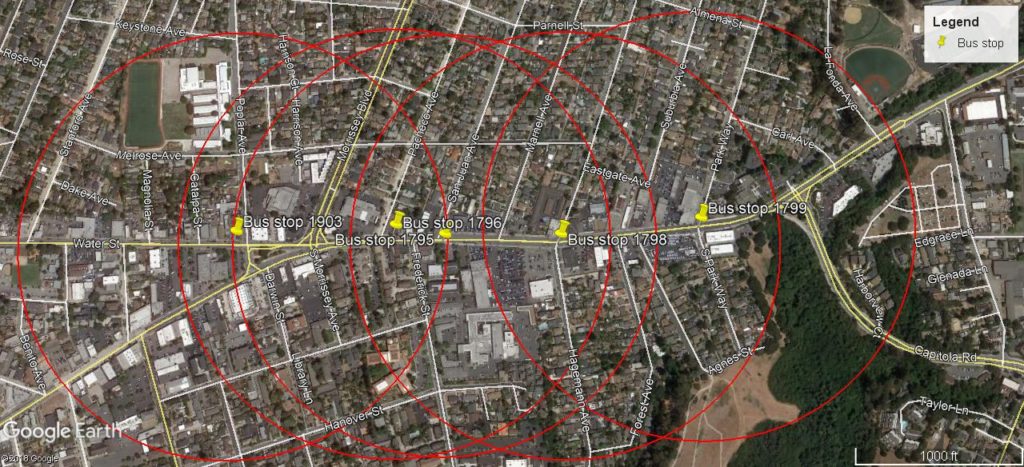

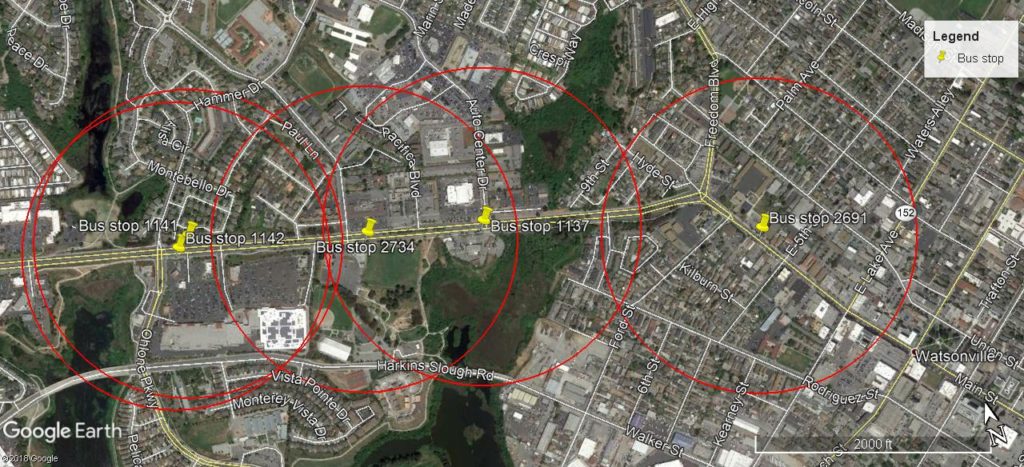

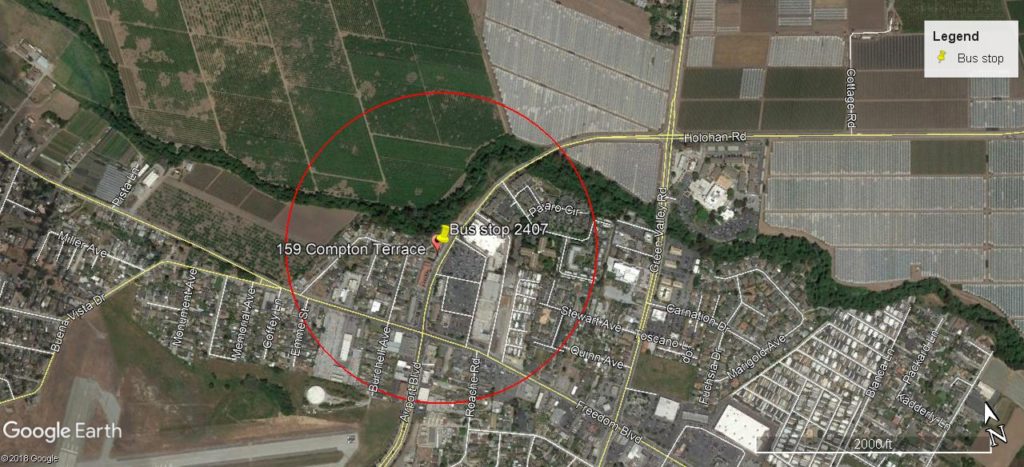

OK. Now let’s talk about where the busy bus stops are. I asked our local transit authority, Santa Cruz Metro, where the bus stops are that fit SB 50’s criteria.

Then I mapped those stops, and drew a quarter-mile radius around each, and came up with a sketch of where SB 50 would allow apartments.

Basically, it’s a swath through Santa Cruz’s downtown and Westside, along Laurel Street and Bay Street. There’s another strip on the Eastside, along Water Street and Soquel Avenue. Watsonville has two areas: on Main Street, from downtown to just past Ohlone Parkway, and on Airport Boulevard, near the Safeway.

Those maps are also posted on our website, santacruzlocal DOT org.

So. If you’re hearing this and getting riled up about it, you’re not alone. I overheard one Santa Cruz resident speaking heatedly to Senator Wiener after his talk, about what SB 50 would do to her neighborhood.

Opponents are upset that the bill takes away local control. Some say what works in a major city wouldn’t work in this city. Others say the bill would have an unintended consequence. Cities would remove or limit transit service as a way to block development. Still others say the bill doesn’t do enough to combat gentrification.

MUSIC BREAK

Another thing you should know about local housing is that Santa Cruz, Capitola, Scotts Valley, Watsonville and Santa Cruz County are behind in their housing development goals. Probably no surprise there. But I think you should know exactly how far behind our local governments are.

Want more deep dives on local issues? Help us get to our launch.

CONTRIBUTE TO SANTA CRUZ LOCAL

For example, let’s drill down on Santa Cruz. It’s about to get a little complicated here, so bear with me.

What we’re talking about is RHNA goals, spelled R-H-N-A, which stands for Regional Housing Needs Allocation. These targets come down from the state.

The city is supposed to issue permits for 180 units of affordable housing for people with very low incomes. The deadline is the year 2023, and the clock started ticking in 2015.

Last year, the city issued just six of those 180 permits. The year before, zero permits. The year before that, one permit. At this rate, the city will never reach its goal.

Also just because permits have been issued doesn’t mean they’re built yet. And that’s just looking at permits issued, not what’s actually getting built. Those six building permits issued for very low income housing? None of those units were completed.

Another example: Last year, the city issued 53 permits for low income housing. Just two were completed.

It’s a similar story around the county. For example, Capitola is supposed to issue 83 permits for affordable housing between 2015 and 2023. By the end of 2017, it had issued just one.

Scotts Valley? That city didn’t even make any RHNA goals.

[MUSIC BREAK]

So, why do these numbers matter? Because our local governments could miss out on funding.

Governor Gavin Newsom plans to reward money to cities moving toward their goals. He set aside $500 million in his draft budget. It’s still early to say what that might look like though. The budget will be revised in May and will be debated on in the Legislature.

Here’s another reason why RHNA goals could become a big deal. Governor Newsom has said that he would withhold transportation funding from local governments that aren’t meeting their goals. That plan has been delayed though, until 2023. We don’t know what that plan would look like yet either. Santa Cruz is way behind on its very low-income housing goal, but that’s the norm for the state. So the Santa Cruz is actually doing OK by comparison.

Also, quick side note, there’s one rule already in effect: Because Santa Cruz is behind on its goal, the city already has lost some control. Developers with certain projects that are 50 percent affordable housing automatically get a green light. So far though, in Santa Cruz, that rule hasn’t resulted in more affordable housing.

[MUSIC FADE IN]

Before we go, I wanted to tell you about something new that we’re trying. We don’t have a catchy name for it yet, but for now, let’s call it “audio letters to the editor.”

Part of what we’re doing at Santa Cruz Local is trying to talk about solutions, and we want to hear ideas from you.

On Tuesday, the Santa Cruz City Council is set yet again to talk about the closure of the Ross homeless camp. As we’ve talked about before in previous episodes, the city seems locked in an endless cycle of opening and closing, and reopening homeless camps.

Now it looks like the city is going to close the Ross Camp on April 30 and reopen the 1220 River Street Camp. If it turns out that there’s not enough shelter beds for the people living at Ross Camp, then the city’s just not going to enforce its camping ban.

Do you have a better idea of how the city could approach this problem?

Send us a voice memo. You know, that little app on your iPhone or Android where you can record yourself speaking? Send us a 20-second clip — and I’m talking 20 seconds, max — on how the city could solve its problem with homeless camps. We’ll publish the best ones with our city council episode that will come out on Wednesday.

Email your 20-second voice memo to [email protected].

That’s it for this episode. Thanks for listening to Santa Cruz Local. I’m Kara Meyberg Guzman.

Thank you to Stephen Baxter for your work editing this episode.

Music was by Bobby Cole and Podington Bear, at Sound of Picture dot com.

Kara Meyberg Guzman is the CEO and co-founder of Santa Cruz Local. Prior to Santa Cruz Local, she served as the Santa Cruz Sentinel’s managing editor. She has a biology degree from Stanford University and lives in Santa Cruz.