Michael Rodriguez, left, picks up litter on Second Street in Watsonville in February. Sandra Valera, second from left, is the program’s coordinator. The program is a service of the Community Action Board of Santa Cruz County. (Patrick Riley — Santa Cruz Local)

WATSONVILLE >> On a brisk February morning in Watsonville, Esmeralda Chavez began her workday scanning the ground for cigarette butts, candy wrappers and other litter.

From a warehouse not far from downtown, Chavez and others with the Watsonville Works program fanned out on foot and by van. With garbage bags and trash grabbers, they scoured sidewalks, roads and train tracks to remove others’ trash.

Chavez, 47, grew up in Watsonville. She worked at a restaurant in Santa Cruz. Then, about three years ago, she started using drugs while going through a divorce. Her situation quickly spiraled. She ended up without a place to live and she lost custody of her children.

“The hardest part for me is not having my children with me,” Chavez said. She stayed at friends’ homes, at a shelter and, for a couple weeks, on the streets. She now sleeps in a friend’s car. She has been sober for about eight months. Her driving force is to get her children back, she said.

Chavez cleans the streets a few mornings each week with the Watsonville Works program. It’s run by the Community Action Board of Santa Cruz County. Participants earn $25 gift cards for toiletries and other necessities. Watsonville Works staff also try to connect participants with job placement services and state health and food programs like Medi-Cal and CalFresh.

Shelters are more difficult to get in, Chavez said. Police make it hard for unhoused people to stay in one place, she said. Chavez said people often make assumptions about unhoused people that aren’t true.

“It’s really just people that have struggled and they’re trying to get back on their feet,” Chavez said. She said she wants to find a job in social services or a related field. “I would love to help people,” she said.

In recent months, many who work with the homeless in Watsonville said they have seen an uptick in unhoused people. Social service providers, police, city officials and other residents said several factors have played into a perceived rise in homelessness in the city.

- An emergency shelter at the Watsonville Veterans Memorial Building was closed in 2021 after pandemic-related money dried up.

- A persistent shortage of affordable housing. Santa Cruz County leaders estimate that more than 10,000 units of affordable housing are needed for “very low income” and “extremely low income” residents.

- Some unhoused people have told service providers that the pandemic has been a cause or factor in their lack of housing.

- Some people have come to Watsonville to look for work. Some have come from places like San Francisco and San Jose for various reasons, service providers said.

- Police say more services and facilities are needed to deal with mental health issues and long term care.

An official count of the unhoused in Watsonville and the rest of Santa Cruz County is set for later this month. But some longer term data sheds some light on the situation.

There have been about 1,900 to 3,500 unhoused people in Santa Cruz County since 2009, according to point-in-time counts. Nearly 75% of unhoused people said they were housed in Santa Cruz County before they became homeless, according to a 2019 report. More than 30% said they had jobs and 19% said they had children with them, according to the 2019 report.

In Watsonville, a 2017 point-in-time count tallied 463 unhoused people in Watsonville. All point-in-time counts have some data limitations. A 2019 point-in-time count tallied 370 unhoused people in Watsonville. No official count was taken in 2021 because of the pandemic.

As some people find homes, others become homeless.

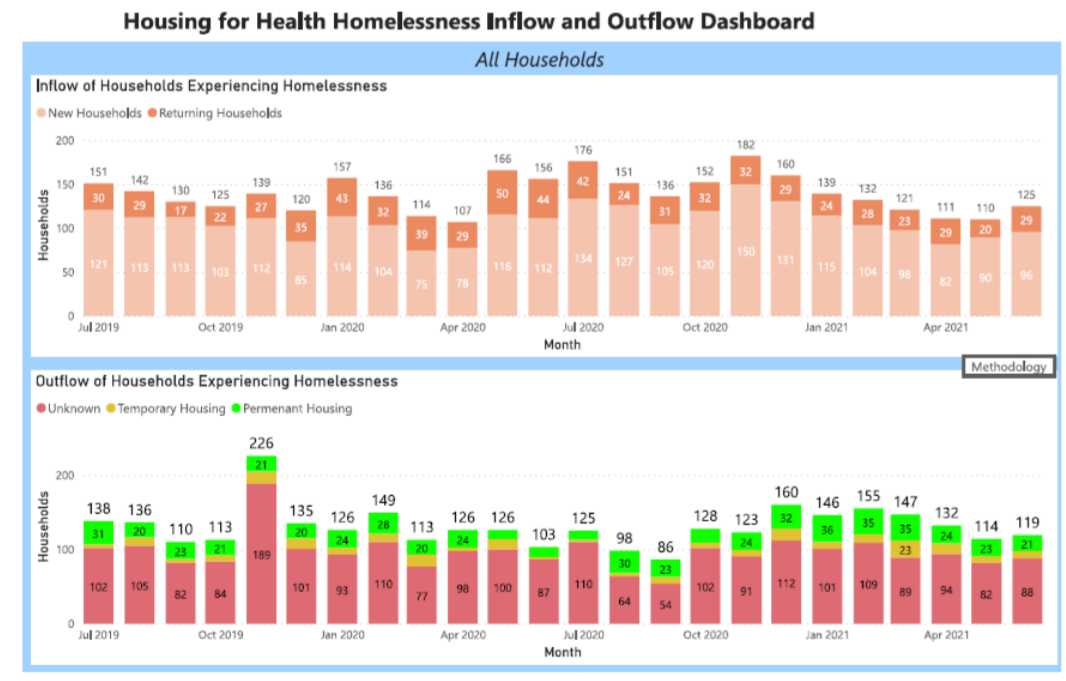

About 20-30 households found permanent homes each month from January to June 2021 in Santa Cruz County, but more than 80 new households became unhoused during those same months, according to a county report.

Charts show estimates of Santa Cruz County households that became homeless and found housing from 2019 to 2021. (County of Santa Cruz)

Housing crunch hits Watsonville

Watsonville’s homeless used to be a lot more hidden, said Paz Padilla, programs impact director for the Community Action Board.

“Seldom would we see them, but we knew that they were in these specific locations throughout Watsonville,” she said. Tents have long been pitched near the Pajaro River levee, for instance.

With the pandemic that started to change. Santa Cruz County leaders opened an emergency shelter at Watsonville Veterans Memorial Building. Before it closed in late 2021, county leaders tried to secure hotel rooms for its occupants, Padilla said. But not everyone made the move. A Salvation Army shelter remains open, but Padilla and her colleagues started to see more unhoused residents in the city, especially in the downtown plaza area.

“All of a sudden this has become a meeting place,” Padilla said. “So it’s been increasing.”

Demand for the Community Action Board’s homeless services, including its Watsonville Works program and its youth Homeless Response Team, rose in 2021, Padilla said.

Homelessness in Watsonville can be caused by many factors, Padilla said.

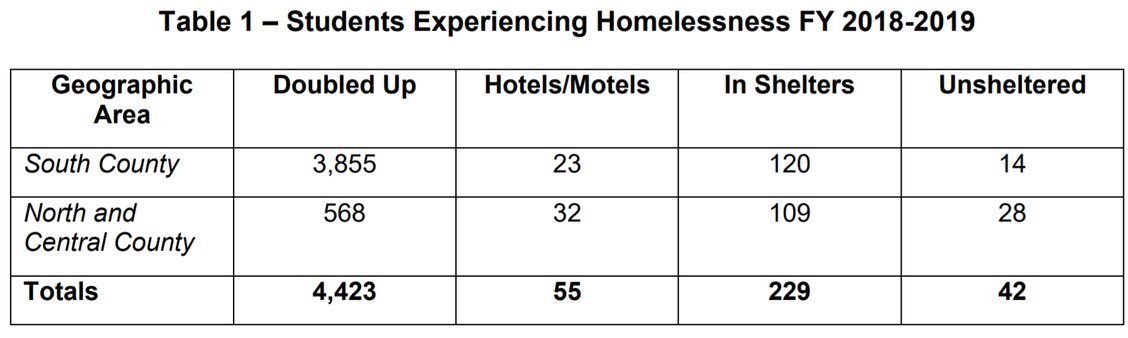

A dearth of higher paying jobs and affordable housing can force multiple families to live under one roof, she said. The Santa Cruz County Office of Education, for instance, estimated that 3,855 of its Kindergarten through 12th grade students were “doubled up” in South County homes during the 2018-2019 school year.

The Santa Cruz County Office of Education has tracked students’ housing situations. (Santa Cruz County Office of Education)

Another factor is that some Watsonville rents have become untenable. Families who spend more than 30% of their income on housing are considered “rent burdened,” according to federal and state authorities.

- In the United States on average, a household needs to earn at least $24.90 per hour to afford a modest two-bedroom rental at “fair market rent” without spending more than 30% of its income on housing, according to a report by the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

- In the Santa Cruz-Watsonville Metropolitan Statistical Area, a household would have to earn $58.10 an hour for that two-bedroom rental, the report stated.

- It’s about the same in the San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara Statistical Area, and the hourly wage would have to be $68.33 in the San Francisco area.

- The three regions – with Santa Cruz-Watsonville in third place – lead all metropolitan areas nationwide as the most expensive jurisdictions, according to the report.

Mayra Melendrez knows the pressures on Watsonville families well. She is the program director for Community Bridges’ Family Resource Collective, which includes Watsonville-based La Manzana Community Resources.

The organization provides a range of services, from helping clients navigate state rental assistance programs to offering legal support for people facing eviction. La Manzana averages about 35 to 40 families who seek help daily, Melendrez said.

Like other service providers in Watsonville, La Manzana saw an increase in demand last year, especially on the rental assistance front. Melendrez estimated a 15% increase in demand for services from 2020 to 2021.

During the past few years, the Watsonville organization also has helped more people just across the Pajaro River in north Monterey County. When Melendrez first started working at the Watsonville location about six years ago, there were roughly 300 Monterey County clients. Now there are about 500, she said.

“I would say it’s a combination of need and word of mouth,” Melendrez said of the trend.

Two tents are pitched near the Pajaro River bridge in February. The river separates Santa Cruz and Monterey counties, and authorities dismantled a camp near the river after a Monterey County court ruling in December. (Stephen Baxter — Santa Cruz Local)

Not far from Melendrez and La Manzana, Pajaro Valley Loaves and Fishes helps feed those in need from Monday through Friday. Each month the pantry serves about 800 families and individuals, said Ashley Bridges, Loaves and Fishes’ executive director. The lunch program serves 600 meals a week.

When the pandemic first hit, Loaves and Fishes saw a big rise in demand, Bridges said. About six months later, it leveled to roughly 10% to 15% more than average before the pandemic, Bridges said.

The nonprofit group, a few blocks from Watsonville’s downtown, serves a hot meal to-go from noon to 1 p.m. each weekday. From 9 to 11:30 a.m. and 1 to 3 p.m., Loaves and Fishes’ pantry also provides supplemental groceries, fresh produce and food bags for individuals and families who don’t have access to a kitchen. Bridges said people need water. They give out bottled water, but Bridges’ goal is to one day have a refillable water station.

Bridges always tries to put herself in her clients’ shoes. She said that with a few bad breaks — like a lost job, an expensive medical problem, or both — her family could be among those seeking help at Loaves and Fishes.

“There’s a reputation or a stigma that people are lazy,” Bridges said. “I can tell you that the people who come are not lazy. They come as they are. A lot of times they’re coming right from work. Or they are in the middle of a mental health crisis. Or whatever life throws at them.”

Among those visiting the pantry on a recent afternoon was 56-year-old Andres Sandoval. A plumber by trade, he said he has been sleeping in his vehicle by a river for about three years. He said that once a person becomes homeless, it’s hard to pull oneself back to a more stable situation, said Sandoval.

“Because you’re starting not from zero — less than zero,” Sandoval said.

Andres Sandoval, 56, has worked as a plumber. He lives in his vehicle in Watsonville and wants a more stable situation. (Stephen Baxter — Santa Cruz Local)

If homelessness is a maze for the unhoused, it can also be frustrating and complicated for Watsonville residents and police.

Watsonville Police Chief Jorge Zamora said that about 7 in 10 of its calls for service are related to homelessness, mental illness or drug and alcohol addiction. That’s based on patrol sergeants’ estimates and not hard data, he said, but it seems like more than in the past.

“I see people walking down the street and they’re clearly mentally ill,” said Zamora, a Watsonville native. “They’re clearly in need of support. And it’s just almost like a moral tragedy to not have those facilities for them. And to leave them out in the street, I just think it’s wrong,” Zamora said.

Zamora said there is a lack of residential care shelters, psychiatric beds and long-term care facilities for those needing lifelong care, especially people with mental illness.

When police interact with unhoused people, it’s often because of a nuisance. Someone might be camping illegally, trespassing or leaving waste where they shouldn’t.

Each case is different, too. Sometimes it might be a homeless single mother with teenage children. Other times it might be a person with a mobile home “and they decide that they’re going to just park someplace and take that little area over and defecate and urinate in, you know, in the sewer,” Zamora said.

“There’s a difference there about how that is approached, and what remains the same is we still offer services to both of those individuals,” Zamora said. One person may take them up on it and the other may not, he added.

Not everyone is willing to follow shelters’ rules, Zamora said. And just because an officer is called to an incident does not necessarily mean there is a crime.

“Nowadays, an arrest may just mean that you get a citation with a court date and then you get released back into the community — even though you may need help right now,” Zamora said. “There might be a strong need for intervention, but that doesn’t happen.”

Like so many California cities, police officers in Watsonville are often the default responders to problems related to homelessness. But they may not always be the person best equipped to deal with the situation.

One change since 2016 has been Watsonville police’s Crisis Assessment Response and Engagement team, or CARE team. It can be sent to respond to mental health-related calls, and it includes two police officers and a Santa Cruz County mental health clinician.

Zamora sees mental health and addiction issues as a large part of the problem. But even so, it’s hard to narrow it down to one single factor.

“I think the larger system has kind of failed us,” he said. “And, you know, while there are very good programs out there, very good people trying to help the issue, I don’t think it’s solving the issue.”

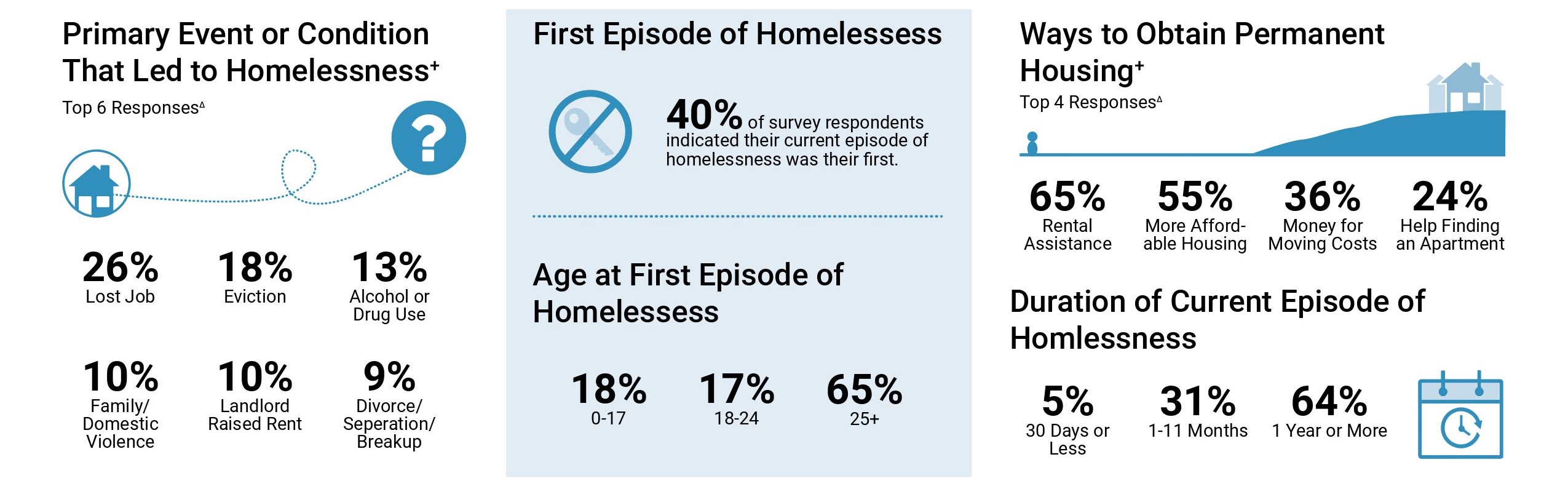

A 2019 study of homeless residents in Santa Cruz County suggested that raised rents, evictions and family problems helped lead to homelessness. (Applied Survey Research)

City officials grapple with homelessness, housing needs

Watsonville city leaders also said they have grappled with homelessness in recent months.

Some business leaders, particularly in Watsonville’s downtown area, have become more vocal about “issues,” said Interim City Manager Tamara Vides. Vides said that without data it’s not clear if that is specifically related to a rise in unhoused people.

However, Vides said a homeless camp developed in the city after Monterey County leaders won a legal battle to dismantle a homeless camp along the Pajaro River levee in December.

Vides pointed to several initiatives to keep people housed and deal with homelessness.

- The city’s eviction moratorium, first instituted at the outset of the pandemic. Watsonville was Santa Cruz County’s first jurisdiction to adopt protections for renters hit by the pandemic.

- Watsonville leaders are working with Monterey County authorities on a longer-term strategy, Vides said.

- City officials are also looking to improve outreach efforts to unhoused residents, Vides said. “How do we organize ourselves so that if I am going to serve you, I just know all the resources and be creative and be able to utilize the systems that exist to the maximum potential?” she asked.

- Watsonville and its city council have made a “significant investment” in rental assistance efforts, Vides said.

Hundreds of Watsonville residents applied for rental assistance but not everyone has received it. At least 900 Watsonville households applied for pandemic-related rental help from the state and 307 households received it, according to a state dashboard.

In an informal survey and Santa Cruz Local interviews with Watsonville residents this fall, the high cost of rent and lack of rent money were among the top issues.

Public forums also have cast light on homelessness in the city. A Jan. 11 Watsonville City Council meeting included several pleas for more action. A tent camp was cleared on Bridge Street in late December. City officials said temporary shelter was provided for everyone who was displaced, but some residents questioned what the city was doing to find long-term solutions. They also asked how the city spent money on homeless services.

“People need stability,” resident Sophia Bassett said at the Jan. 11 council meeting. “And they need a safe shelter. So I’d like to know what options the city will be having going forward,” Bassett asked.

“Can we not displace people constantly?” another resident asked. “What is the point of that? You’re just making their lives harder, and they already don’t have much.” She said, “We have to do more about affordable housing in the first place.”

Vides, the interim city manager, said she expects conversations on how to best tackle homelessness to continue and intensify. “This moving or displacing is not really ideal, I think, for anyone,” Vides said in an interview.

Watsonville leaders also have been working closely with Santa Cruz County officials on the issue in part because homelessness should be dealt with regionally, Vides said.

Like many Santa Cruz County leaders, Vides said she sees housing as a crucial element to solving homelessness. There need to be different tiers of housing available, she said, from overnight shelters to assisted living homes and Housing Choice vouchers, formerly known as Section 8 rental vouchers.

Watsonville, among other places in the county, could be a site for Project Homekey housing, Vides said. Project Homekey is a statewide effort to sustain and rapidly expand housing for unhoused people and those at risk of homelessness. Through state grants, local governments can develop housing from single-family homes to apartments to mobile or manufactured homes.

At 1620 Beach St. in Watsonville, Project Homekey could convert a Rodeway Inn into a 50- to 90-unit permanent supportive housing project that would include case managers on site. Santa Cruz County staff and a Los Angeles-based developer planned to apply for a state grant to cover costs of the potential $32 million project, county leaders have said.

“I think that’s very exciting and, fingers crossed, that will come through,” Vides said.

Informal networks for housing

Back at the street cleaning program of Watsonville Works, Program Coordinator Sandra Varela said she often taps her own personal network to help connect participants with jobs and housing.

She works with friends and family to try to find rooms to rent. “Even if it’s a garage,” Varela said. “I’d rather have them in a garage than have them out on the streets.”

Finding permanent jobs is challenging, too. Many program participants have been homeless for so long they don’t have their IDs or Social Security numbers for applications. Or they’re older and are often overlooked as job candidates. Even after participants complete their 12 days of work and graduate from the Watsonville Works program, Varela and others continue to counsel them for up to six months.

Michael Rodriguez, right, and Sandra Valera, center, remove trash near Walker Street in Watsonville on Feb. 16. Valera is the coordinator of the Community Action Board of Santa Cruz County’s Watsonville Works program. (Patrick Riley — Santa Cruz Local)

Varela’s brother has a barber shop in Watsonville. She said she’s arranged for program graduate Michael Rodriguez to clean the shop’s windows. “It’s only a few hours, but it’s something extra for Michael,” Varela said.

Rodriguez, 61, worked in landscaping and construction. He struggled with drug addiction, and abscesses caused him to lose his left arm, he said.

“I lost everything,” Rodriguez said. “My house, my family, my dignity.”

He said he has lived at the Salvation Army shelter in Watsonville for nearly two years. Four months after he started the Watsonville Works program, he still volunteers with the group. On a recent morning, he picked up litter outside the warehouses and garages of Walker Street.

Rodriguez is sober now. But it’s a daily battle, he said. His dream is to start his own landscaping company. He wants to save up enough money to move out of the shelter and into his own place.

“This is my goal for this year,” Rodriguez said.

Santa Cruz Local’s news is free. Our newsroom relies on locals like you for financial support. Our members make regular contributions, starting at $19 a month or $199 year.

Patrick Riley is a Santa Cruz-based freelance reporter. He has covered a range of topics and beats in Florida and California.