Santa Cruz County has an injection drug use problem and a needle litter problem. We look at Santa Cruz County’s needle exchange program and how it compares to other programs in the state. What can Santa Cruz County’s health department learn from San Francisco’s needle cleanup program? What are the trends with Santa Cruz County’s injection drug use? How can Santa Cruz County get more inject drug users into treatment? We hear from Supervisor Ryan Coonerty, county health officer Dr. Arnold Leff, San Francisco Department of Public Health program manager Eileen Loughran, Santa Cruz County Sheriff-Coroner’s Office forensic pathologist Dr. Stephany Fiore, Janus of Santa Cruz Director of Medication-Assisted Treatment Amanda Engeldrum Magaña and Harm Reduction Coalition of Santa Cruz County co-founder Denise Elerick.

TRANSCRIPT

[Theme music]

Kara Meyberg Guzman: I’m Kara Meyberg Guzman. And this is Santa Cruz Local.

In the past few weeks, a proposal for a mobile needle exchange program for locations in Santa Cruz County has drawn significant opposition from residents, elected officials and law enforcement.

On Wednesday, the volunteer group that authored the proposal withdrew its application from the California Department of Public Health.

I exchanged a few emails with the group’s leader, Denise Elerick, on Wednesday. She’s a co-founder of the Harm Reduction Coalition of Santa Cruz County, the project’s lead. She didn’t give a reason for the withdrawal. I asked her if the group plans to change the application then reapply to the state.

Here’s what she wrote: “Where to go from here is up to a coalition of people and not just me. I’ll be in close contact with the state on where we go from here.” Close quote.

This news was a surprise to me. When I spoke with Elerick on the phone at length on Monday night, she gave no indication that she was thinking of pulling the application.

Over the past few days I interviewed more than a dozen people, trying to get a handle on the county’s problem with injection drug use and needle litter. I was mostly looking into the legitimacy of the proposed program, but I’ll put that aside for now.

But I want to share with you what we learned about how our local government is approaching the problem of injection drug use and needle litter. There’s some good news and some room for improvement.

Let’s start with the good news.

Right now, the county is poised to make major strides with substance abuse treatment. A program called the Drug Medi-Cal Organized Delivery System allows the county to bill the state’s Medi-Cal program for treatment for people with addiction.

Here’s Santa Cruz County Board of Supervisors chairman Ryan Coonerty:

RYAN COONERTY: Two years ago Santa Cruz County joined five other counties in experimenting with allowing Medi-Cal to cover drug treatment in our community. It’s a huge need in our community and in doing so we’ve been able to double the number of beds available to people. It’s still not enough but it’s a major step forward in increasing access to drug treatment in our community.

KMG: The county doubled its number of detox beds, but that’s from eight to 16. There’s still a wait list there. But the program has allowed longer stays in residential treatment, as well as more outpatient services.

Also, the addiction treatment center Janus of Santa Cruz received a $4.6 million grant from the state in 2017, according to a report by Santa Cruz Sentinel reporter Jondi Gumz. The grant is for medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction.

Here’s county health officer Dr. Arnold Leff.

DR. LEFF: The gold standard is medically-assisted treatment on demand, or any treatment on demand really, it could even be residential, for substance users. Now the problem has been that there’s not been that resource available so that people sometimes had long, long waits, or the treatment itself was just not available. We are moving toward and close to getting substance use treatment on demand here in Santa Cruz so that anybody who is ready for treatment can get it right away and is not put on some waiting list so they relapse while they’re waiting. The trick in substance abuse treatment is treatment on demand.

[MUSIC INTERLUDE]

KMG: When Denise Elerick applied to the state to start an independent needle exchange program, it touched a nerve in our community. Almost everyone we contacted was opposed to the project, like Santa Cruz County Sheriff Jim Hart, Santa Cruz County Supervisor Ryan Coonerty, Monterey County Supervisor John Phillips, Watsonville Mayor Francisco Estrada, Santa Cruz Mayor Martine Watkins, former Santa Cruz Mayor David Terrazas and Santa Cruz Police Chief Andy Mills. More than 2,000 people signed an online petition opposing the proposal. The topic was on fire on Nextdoor.

People had many reasons for opposing it. Many are tired of seeing dirty syringes in our parks, rivers and streets. Others said an independent volunteer-run program would not be well-equipped to connect drug users with treatment, and it wouldn’t have enough oversight.

Why did Elerick, a dental hygienist from Aptos, propose a new needle program in the first place?

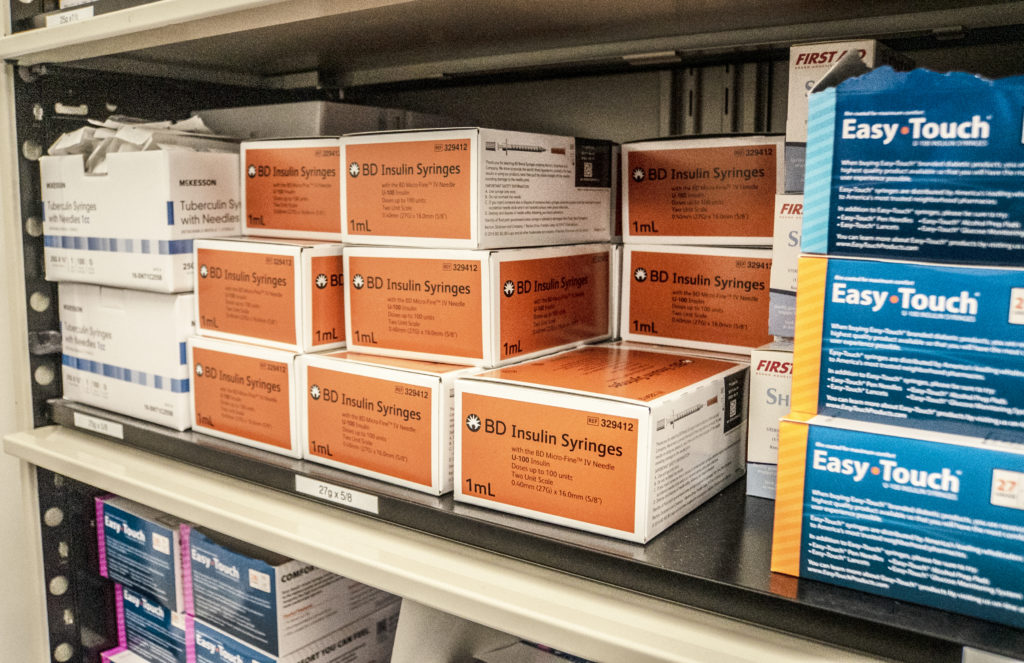

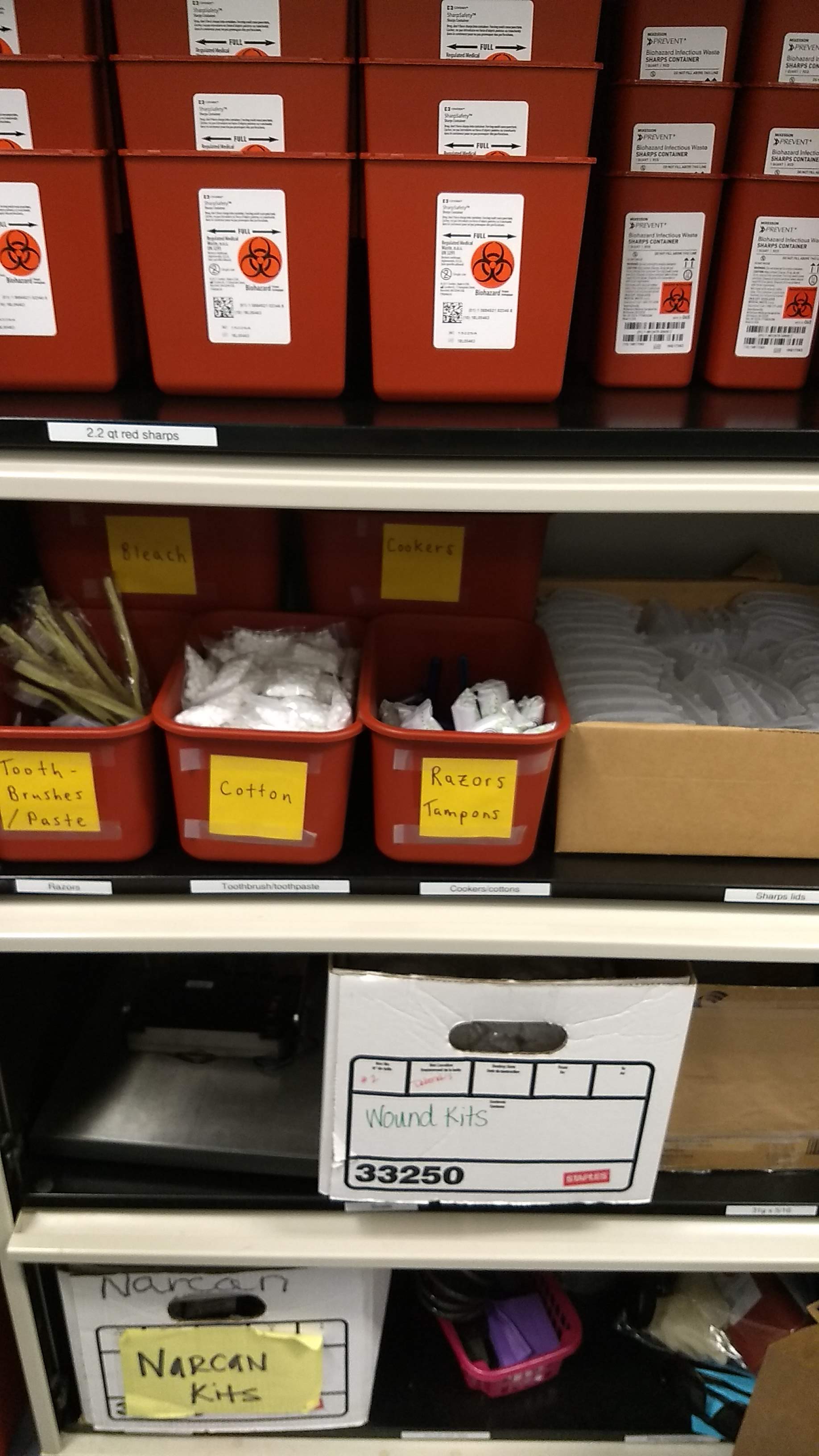

The first thing you should know is that the county health department already has a needle exchange program. It’s run out of the Emeline Avenue clinic in Santa Cruz and at the Watsonville Health Center on Crestview Drive. It’s taken various forms over the years. The county took control of it in 2013 after people were upset about a volunteer-run needle exchange program that operated out of a van at a Barson Street laundromat.

Needle exchange programs give new needles to people who use injection drugs. These programs have been around for decades, and they prevent the spread of diseases like Hepatitis C and HIV.

Both the U.S. Public Health Service and the California Department of Public Health recommend that people who use injection drugs use a clean needle for each injection.

One thing you should know is that our county’s syringe program is actually more conservative than others in the state. It has a one-for-one policy, which means that a client can get a one new needle for every used needle that he or she brings in. Most programs in California have a needs-based policy, which means that a client can get as many needles as he or she asks for, regardless of how many used needles they bring.

The California Department of Public Health actually recommends a needs-based policy, because scientific studies have proven that it cuts the number of dirty injections and rates of needle sharing. That prevents disease.

The topic of needle exchanges has been heavily-studied by scientists, because it’s so politically and emotionally charged. Scientific studies have also shown that needs-based policies don’t result in more needle litter. We’ve linked to those studies on our website, santacruzlocal.org.

- Examination of the association between syringe exchange program (SEP) dispensation policy and SEP client-level syringe coverage among injection drug users (Addiction, 2007)

- Syringe disposal among injection drug users in San Francisco (American Journal of Public Health, 2011)

That may sound hard to believe for Santa Cruz residents who have found hundreds of needles in recent years in parks, on beaches and elsewhere.

When I talked to Dr. Leff and Jennifer Herrera, a nurse who oversees the county’s needle exchange program, both said that the county’s program is not enough to meet the needs. The Emeline clinic is not easy to get to. It’s also far from the places where people use drugs, like the San Lorenzo River and Harvey West areas. Also, it’s open less than 10 hours a week, which isn’t enough, they say. The Watsonville site is open five hours a week, and it gets even less traffic.

The county’s needle exchange program sends about a million new needles into the community each year. But the county’s program is only reaching a fraction of the people who use injection drugs in the area, according to Leff and Herrera.

That’s why Denise Elerick and the Harm Reduction Coalition of Santa Cruz County have taken it upon themselves to start their own needle exchange. Besides the proposal which would have brought needle exchange to Harvey West, Felton, Pajaro and Watsonville, Elerick and others have already been handing out needles.

Over the past year, on Sundays before a holiday, when the Emeline clinic is closed, Elerick and others have been handing out needles in Harvey West. And for five months when the Ross Camp was open, Elerick and others would hand out needles there once or twice a week. They would interview the drug users.

ELERICK: Basically what it is they need? What do they want? What works? What doesn’t work? What are the barriers to accessing the Emeline or the Watsonville campuses, real or perceived. And we got a lot of variety of answers, from mobility, the hours, I don’t want to be seen there, there’s cops, there’s security, I’m afraid they’re filming me. I don’t want to be at a computer. They make you see a doctor. I don’t want to see a doctor. And a lot of what we did was just sort of reassuring people that they don’t make you do anything there. It’s an offer, and you’re in charge.

KMG: Since May of last year, Elerick’s group has handed out 122,000 syringes and collected 127,000 syringes, she said.

How is this even legal, you might ask?

Elerick signed up as a client of the county’s needle exchange program, even though she’s not an injection drug user. The needle exchange program allows clients to exchange for others too. In fact, more often than not, clients are coming to exchange needles not just for themselves, but for their friends. The county health department is aware of what Elerick’s group is doing, and according to Dr. Leff, it’s all by the book.

Here’s Dr. Leff on why the county’s needle exchange program needs expansion.

DR. LEFF: Syringe services programs, besides decreasing the incidence of serious infections like HIV and hepatitis C, they do something in many ways more important. They reach people who normally would not be reached. And by reaching those people, some of those folks may be able to be enticed into some kind of residential or medically-assisted treatment.

KMG: OK. So the county’s needle exchange program is not reaching as many people as it possibly could. Let’s turn to the issue of needle litter, because community concern about that seems to be a limiting factor in expanding any needle exchange services. Many people believe that the more needles a program hands out, the more litter we’ll see in our community, even though the data doesn’t support that.

- A comparison of syringe disposal practices among injection drug users in a city with versus a city without needle and syringe programs (Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2012)

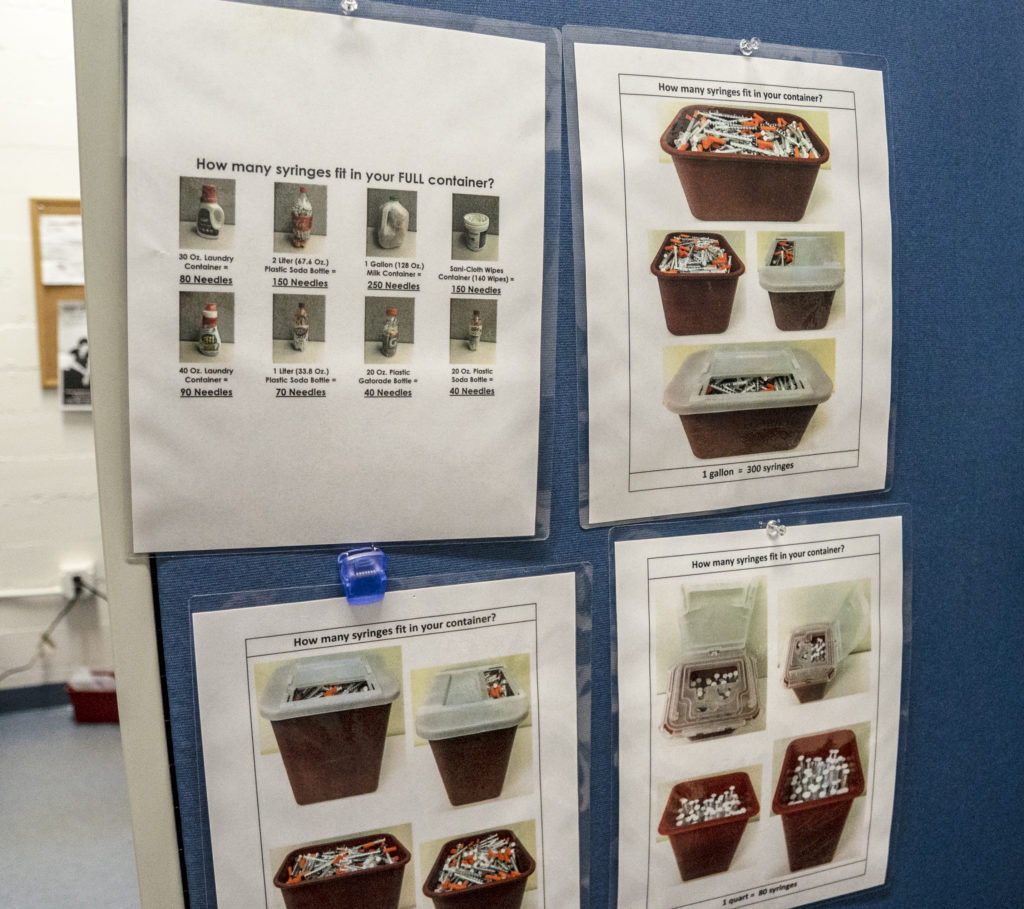

One thing you should know is the county’s program says it has more needles coming in than going out. Three needle disposal boxes in the county help boost the program’s collection numbers. You might have seen them. They look like red mailboxes at the county government building, the Emeline clinic and at the Watsonville Health Center.

Clients also sometimes bring in more needles than they take. More often than not, clients are coming in to exchange needles not just for themselves, but also for their friends. People will come in with maybe 500 needles and ask for just 450 new needles, to give to others too.

And for the most part, according to Herrera, clients in the program are bringing their needles back in the sharps containers and bio boxes the program hands out.

So, if the county’s program is taking more needles than it gives, where are all these needles in our parks and rivers coming from?

Some of the needles might come from stores. A 2015 state law made it legal for pharmacies to sell unlimited syringes to adults without a prescription. You can get needles at most pharmacies, or even on Amazon, for pretty cheap.

Let’s look at how San Francisco is dealing with its needle litter. San Francisco has a pretty progressive needle exchange program that hands out more than 5 million needles a year. The city is also building a pretty robust needle cleanup program. It’s collected half a million more needles in 2018 than it did the previous year. To be clear, San Francisco has not solved its needle litter problem. The city is still handing out 2 million more needles than it’s collecting. But it’s improving, so let’s take a look at it and see what we can learn.

Last June, then-mayor Mark Farrell allowed San Francisco Department of Public Health funds to go to the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, to fund a needle clean-up crew. The cost is $700,000 per year. A 10-person crew runs 12 hours a day, 7 days a week picking up needles around the city. You can text them with a picture of a syringe you’ve spotted, and they’ll reply immediately. Once they find the syringe, they’ll text you back, saying the area is clear.

EILEEN LOUGHRAN:They are able to respond to these sorts of requests within an hour, which is also huge. And they’re really focusing on customer service as compared to 3-1-1, which is responsible for all trash issues, it takes longer for them to respond. Their response will be like 24 hours or maybe 48 hours. And when someone’s upset about syringes, that just doesn’t cut it. When the pickup crew actually goes out, if they encounter neighbors they’re having a very nice, polite conversation with people, like hey, thank you so much for calling, and trying to slip in with the harm reduction conversation of like this is really important work because you know, the syringe programs prevent the spread of HIV and we’re here to pick this up. And it’s actually very effective.

KMG: That’s Eileen Loughran, who works at the San Francisco Department of Public Health and oversees the syringe services program.

San Francisco also has 10 needle disposal boxes throughout the city. They’re the size of large mailboxes. San Francisco also has 14 small disposal boxes in the Tenderloin and SOMA.

LOUGHRAN: Most of those are emptied every other week. There is one location that’s emptied weekly. So I think that is successful because it provides yet another option for disposal. People are getting moved around alot. People don’t want to carry their syringes with them.

KMG: As I mentioned, Santa Cruz County has three needle disposal boxes, all on county property. The county has offered the city of Santa Cruz free needle disposal boxes several times, but so far, the city council has denied the offer. The city has not wanted to be accountable for collecting needles and managing the disposal boxes.

Here’s Loughran again, on how she was able to get San Francisco neighborhoods to adopt more kiosks.

LOUGHRAN: By attending community meetings I heard loud and clear, the issues around syringe litter. And so then, if a hot spot is identified we start talking to partners, well, is this a good location for a kiosk or a small outdoor disposal box. And if it shows a hot spot, with our 3-1-1 data, the next step is to talk to the community that uses drugs, if there was a kiosk here, would you use it and get that input. And then start the conversation with larger community of business owners and other stakeholders and politicians of, this is the proposal. We’d like to pilot a kiosk or box here.

KMG: It’s a slow approach, that relies on asking both the neighborhoods and the drug users whether a kiosk would work there. Loughran said when she talked with drug users, many said they would use disposal boxes if they were available.

[MUSIC INTERLUDE]

KMG: Santa Cruz County’s opioid crisis seems to be leveling off, judging by the numbers of deaths. We hit a peak in 2011, when 67 people died from opioids. Last year, 27 people died from opioids. These numbers come from our county’s Coroner’s office.

Clearly, opioids are still a problem, but it’s getting better.

That’s mostly because deaths from prescription opioids like OxyContin are dropping, as the medical community has become more aware.

But our county’s numbers of deaths from heroin have stayed in the teens since 2012, even as Narcan has become more available. Narcan is a drug that reverses overdoses.

Overview-of-Acute-Drug-Related-Deaths-in-2008-2018Meanwhile, numbers of deaths from methamphetamine have surpassed deaths from heroin. That’s scary because meth is not an opioid, and it’s much harder to treat. People who use meth are more likely to act violently and less likely to seek treatment or join a needle exchange program.

Here’s forensic pathologist Dr. Stephany Fiore, from the Santa Cruz County Sheriff-Coroner’s Office.

DR. STEPHANY FIORE: It makes people crazy. You know, they tend to be different kinds of people, like Dr. Leff said. They’re not people that are ones that you can treat. And they’re usually… where you have heroin addicts that can be bankers and can be functioning. You don’t have functioning methamphetamine addicts. It just destroys people. It’s a scary drug.

KMG: You diehard Santa Cruz Local listeners might remember back in March, we quoted Dr. Leff at a Santa Cruz City Council meeting, saying that 282 patients at the Santa Cruz County health clinics account for $52 million in costs.

Well since then, we fact-checked that with Central California Alliance for Health, and that statistic was totally off. There were more than 10,000 Santa Cruz County patients that accounted for that $52 million price tag.

But, Dr. Leff’s point had a kernel of truth: Santa Cruz County health clinics have a small subset of patients who are very sick, and very expensive to care for. According to the Central California Alliance for Health, which administers Medi-Cal in Santa Cruz, Monterey and Merced counties, 8 percent of Alliance members account for three-quarters of the costs. Most of those high-cost members have addiction or mental health conditions.

Injection drug users are prone to things like brain abscesses and infected heart valves. Those require difficult, expensive surgeries at Dominican Hospital, or sometimes Stanford Hospital or UCSF, says Dr. Leff.

Injection drug users are also prone to sepsis, an extreme reaction to infection, that can require six weeks in the hospital to treat, Dr. Leff says.

So, the point is, it’s in the community’s interest to get its vulnerable population off injection drugs.

The most successful treatment for opioid addiction is medication-assisted treatment. It’s a holistic approach, that combines counseling and things like group therapy with medicines like methadone, which help reduce cravings and withdrawal symptoms. The idea is to help people taper off opioid use.

That $4.6 million grant to Janus that I mentioned earlier, that has brought medication-assisted treatment to clinics all over the county, by training doctors how to provide the medications. Now, many more people have access to this treatment than a few years ago.

I spoke with Amanda Engeldrum Magaña, Janus of Santa Cruz’s director of medication-assisted treatment, on how we could get more people into treatment.

She sees two bottlenecks. One is not enough withdrawal-management detox beds. There are now 16 beds in the county.

MAGAÑA: We’re talking about everyone in the county having to use Janus of Santa Cruz withdrawal management. Encompass doesn’t have a withdrawal management. The county doesn’t have a withdrawal management. The hospital doesn’t have a withdrawal management.

So that to me is the bottleneck that’s very obvious at the get-go. And then the other problem is, of course, you could get some people in, and they go through a residential course of treatment, learn a lot, really make some good progress. And then there’s such a lack of affordable housing in this county, most of them return to the streets.

KMG: So, here we are again, back to our housing crisis. We’ve found that often, when we’re digging into some issue in Santa Cruz County, if we pull on a string for long enough, it eventually leads us back to affordable housing.

I’ll leave you with one thought, tying it back to where we started. Here’s Denise Elerick, the volunteer who’s trying to create a mobile needle exchange.

ELERICK: People in houses are not taking their syringes and going and dumping them on the river levee or dumping them at the beach. So until we turn the tide and move into some kind of better sheltering or transitional housing. I mean the real issue is housing or a place to safely use. And it just happened that these two explosions with homelessness and the opioid crisis and substance use in our community, it all sort of swirled into this horrible tide.

[MUSIC FADE IN]

KMG: That’s it for this episode. If you’d like to comment to the board of supervisors about the needle exchange program, they will be discussing the program at their June 11 meeting.

You can visit our website, santacruzlocal DOT org, to see photos, data tables and links that go along with this story. Our script was edited by Stephen Baxter. Our theme music was by Podington Bear, at soundofpicture.com.

I’m Kara Meyberg Guzman. Thanks for listening to Santa Cruz Local.

Kara Meyberg Guzman is the CEO and co-founder of Santa Cruz Local. Prior to Santa Cruz Local, she served as the Santa Cruz Sentinel’s managing editor. She has a biology degree from Stanford University and lives in Santa Cruz.