A property near Boulder Creek stands damaged in 2020 after the CZU Lightning Complex Fire. (Stephen Baxter—Santa Cruz Local file)

FELTON >> Diantha Lowery recalls how ash was falling like snow when firefighters told her she had 15 minutes to leave her home. That night, the CZU Lightning Complex Fire ripped through her home of three years, burning so hot that it cracked the concrete in her driveway.

A year later, Lowery and her husband are still waiting for permits to rebuild their home in the Upper Big Basin neighborhood of Boulder Creek.

“It’s a nightmare,” she said. “We’ve been trying to get permits for months.”

Lowery isn’t alone. More than 900 homes burned down in the Santa Cruz Mountains last summer. Despite efforts to speed up the permitting process, just 42 building permits have been issued to fire survivors with another 18 building permits in process, county officials said in mid-August. County representatives said they expect to receive another 240 applications in the coming months.

Fire survivors, growing more desperate as they run out of insurance money, are calling on the county to lift some regulations to help accelerate the process.

- Fire survivors said that health and safety regulations, such as geological surveys to assess debris-flow risk on their properties, are expensive and can add months to the permitting process.

- The county is exploring measures to speed up the process. Santa Cruz County Supervisors Bruce McPherson and Ryan Coonerty submitted a proposal to the board of supervisors Aug. 11 to forgo the assessment of geological hazards that predate the fire.

A van and a car stand among ashes at Diantha Lowery’s property near Boulder Creek after the CZU Lightning Complex Fire in 2020. (Diantha Lowery—Contributed)

Stuck Before They Start

In the wake of the CZU fire, county leaders created the Recovery Permit Center to help fire survivors navigate the complexities of rebuilding their homes. The center exclusively processes permit applications from fire survivors. Paia Lavine, Santa Cruz County’s assistant planning director, said that most applications are approved within two weeks of submission. County leaders said that turnaround time is faster than other county permit processes.

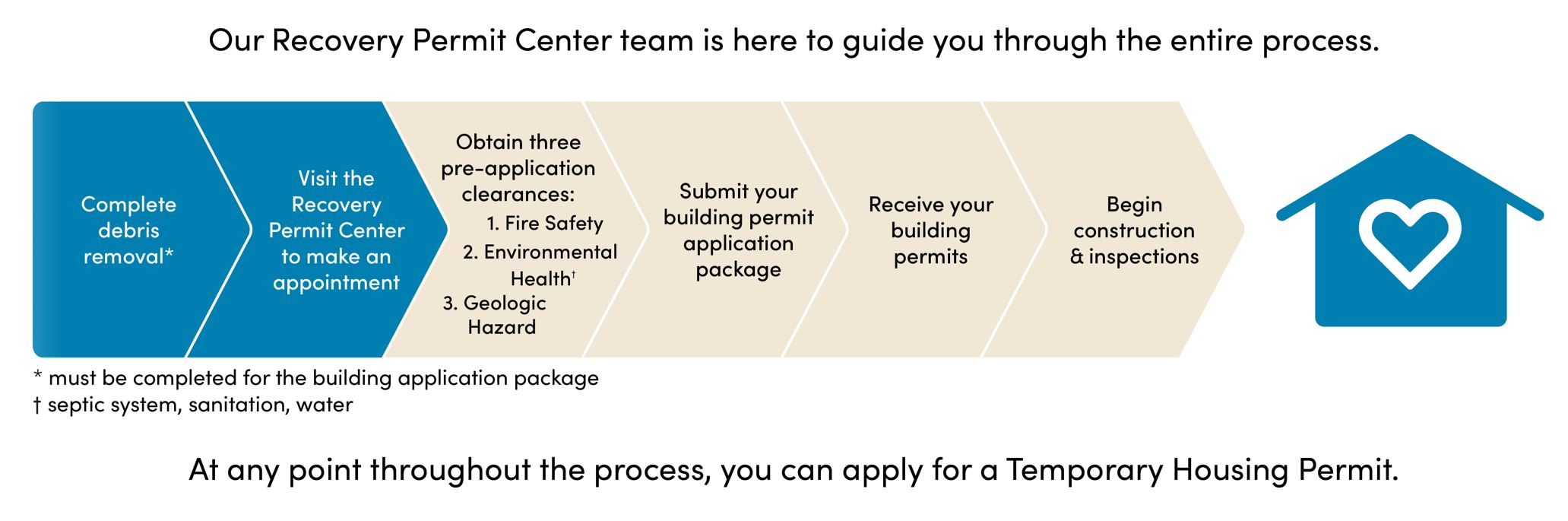

But as fire survivors like Lowery discovered, the real challenge comes before even submitting an application. The Recovery Permit Center lays out a multi-step process for rebuilding. After clearing a property of rubble — a service performed by the county — fire survivors development plans must pass several health and safety regulations before they can apply for a permit.

Santa Cruz County’s Recovery Permit Center has a multi-step process to rebuild in the CZU fire zone. Many fire survivors struggle to complete pre-application clearances. (County of Santa Cruz)

Antoñia Bradford, a fire-survivor advocate who lost her home last summer, said the pre-clearance application is where most survivors get stuck. County and state regulations have changed over the years, meaning that many properties developed decades ago are no longer up to code.

Bradford says that meeting these new standards is expensive and time-consuming. Geological hazard surveys — where geologists assess the risk of earthquakes and landslides — is a major sticking point for survivors like Bradford.

“The county is treating fire victims as if our parcels were never developed,” she says. “But my house was built with permits in 1971. They shouldn’t be making me do expensive geological reports.”

County officials said the reports help protect residents and their homes from landslides and other threats.

Debris flow and other hazards

Lowery, whose Boulder Creek home was destroyed, now lives temporarily in San Jose. She said the pre-application process has bogged her down as well. “We thought that since the property was cleared and ready to go that we could start building,” she said. “Then we found out that we need to get clearance.”

Lowery says that county officials have asked her for another geological hazard survey in addition to the one provided by the county after the fire. Jeff Nolan, a geologist at the County of Santa Cruz, said that fast-moving slides called debris flows are a major concern for the county.

After a wildfire in 2018, 23 people in Montecito died after a debris flow destroyed homes in the middle of the night. The risk of a debris flow was heightened by the loss of vegetation during the wildfire.

“We didn’t want to have another catastrophe,” said Santa Cruz County Supervisor Bruce McPherson. McPherson’s fifth district includes the San Lorenzo Valley and many areas west of Highway 9 that burned in the CZU Fire. “So there was a reason not to rush in and let people rebuild right away.”

But for fire survivors like Larry Green, these surveys represent another barrier to rebuilding. Green lost his home off China Grade north of Boulder Creek. He’d lived there for 38 years.

“I have to go hire a geologist and get a more detailed report than what the county’s done, but all the geologists are full,” says Green. “My house burned down Aug. 20, (2020) and I’m no closer to getting a permit than I was Aug. 21.”

Making Moves

As fire survivors mark the one-year anniversary of the CZU fire, nonprofit and county leaders are trying to hasten the permit process.

- County leaders expect an extensive debris-flow report commissioned by the Community Foundation of Santa Cruz County in mid-September. “The study is saving all property-owners applying for permits to not have to pay for their own study,” said Susan True, CEO of the Community Foundation of Santa Cruz County. “We expect that many properties that were in the prior debris-flow areas will no longer be considered in the hazardous zones as the study is more refined.”

- On Aug. 11, the county board of supervisors unanimously voted to find ways to speed up the permitting process for CZU fire survivors. Supervisors McPherson and Coonerty proposed to allow fire survivors to skip geological surveys that require them to assess hazards that pre-date the fire.

Bradford, the fire survivor advocate, said these moves are “the first genuine positive movement in the direction of supporting fire families.” But she added that efforts to help are coming too late for some survivors. As insurance money begins to run out, some fire survivors have chosen not to rebuild.

“I know people who said that if they lost their homes in the fire, they weren’t going to rebuild because Santa Cruz is a no-build county,” says Bradford. “The county is trying their best, but the system is working against the people it needs to be working for.”

As for Lowery, who lost her home, she agreed that the permitting process “could be a little easier.” And while she doesn’t expect to start rebuilding anytime soon, she and her husband intend to stick it out.

“We’re not giving up hope,” she said.

Become a member of Santa Cruz Local, an independent, community-supported newsroom that’s owned and led by local journalists. Our stories are free and always will be, but we rely on your support.

Already a member? Support Santa Cruz Local with a one-time gift.

Freda Kreier is a science journalist and graduate of UC Santa Cruz's science communication program. Her work has appeared in Nature, The Mercury News, Good Times and more.