Editor’s note: Santa Cruz Local’s team digs in to reader and listener questions. Submit your questions to [email protected].

“Do we have a sufficient, sustainable water supply to support new housing at the densities proposed?”

—Nancy Drinkard, a Santa Cruz resident and Santa Cruz Local member

SANTA CRUZ >> With many recent housing proposals in Santa Cruz County, residents have questioned the impact of new development on water demand.

The answer is counterintuitive, water officials said. Despite population growth in Santa Cruz County in recent years, total water use has declined, according to county water officials and data. It’s largely because of a culture of water conservation, water-saving technology in appliances and building codes, water district leaders said.

“It’s not enough to say that water use has remained consistent over the years,” said Sierra Ryan, the interim water resources manager of Santa Cruz County. “Water use has gone down, significantly.”

The problem today — even if no more homes were built — is a lack of water storage and overdrawn groundwater basins. The city of Santa Cruz’s water supply is dependent on winter rain and needs more storage capacity to endure droughts, a city water leader said. Soquel Creek Water District and other large water districts in the county are dependent on groundwater. Underground aquifers in the Mid-County and Pajaro Valley basins and the Santa Margarita basin in the Santa Cruz Mountains are drawn down faster than the rains replenish them.

Today’s population is about 65,000 in the city of Santa Cruz and 273,000 in the county, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. If the county were to grow by 24,000 people in the next 25 years — which state and regional governments said is the projected growth — the chief problem in the city of Santa Cruz would still be the need for a more reliable water supply, not increased water demand. For other coastal areas of the county, sea-water intrusion in underground aquifers would remain more of a problem than water demand.

That potential growth includes figures from UC Santa Cruz’s Long Range Development Plan that would add up to 11,700 new students, faculty and staff in the next 20 years. The plan guides future development but doesn’t mandate enrollment or staff growth.

“There is a marginal increase in water demand associated with the anticipated new growth, but that marginal increase is not what is driving our need to augment water supply,” said Rosemary Menard, water director for the city of Santa Cruz. Menard said the city has needed a more reliable water supply for decades.

“That need isn’t being driven or even made significantly larger by the anticipated population growth or additional housing,” Menard said.

The San Lorenzo River is the City of Santa Cruz’s largest water source. It represents about 45% of the water supply. (Kara Meyberg Guzman — Santa Cruz Local)

Water supply

The city of Santa Cruz’s water supply mainly comes from Loch Lomond Reservoir, the San Lorenzo River and other above ground streams, creeks and waterways. The rest of the county’s water districts mainly rely on surface water and underground aquifers. Some of those water districts include Scotts Valley, Soquel Creek and the city of Watsonville’s water department.

Loch Lomond reservoir can hold up to 2.8 billion gallons of water to supplement the San Lorenzo river in the dry season. The reservoir is at 74% capacity. A recent projection shows that the reservoir could drop below 66% by October.

The rest of the county mostly depends on groundwater aquifers. Because underground aquifers are replenished from multiple sources and at varying rates, drought has a delayed impact on groundwater supply. But all of the county’s groundwater basins are overdrawn to some degree, meaning more water is being used than is replenished, water officials said. Near the coast, this diminished freshwater supply allows saltwater to intrude into the groundwater basin and threaten what remains.

“Sea water intrusion is the bane of our existence,” said Ron Duncan, general manager of Soquel Creek Water District. The district serves mid-county from 41st Avenue to La Selva Beach. Its water sources are considered critically overdrafted — the state’s most severe designation. Because of that problem, a new project aims to inject water into basins to try to stem saltwater intrusion.

Water demand

Since the 1980s, there have been wetter-than-average years and years-long droughts. Meanwhile, the population has grown and water connections have increased in homes, businesses and other places.

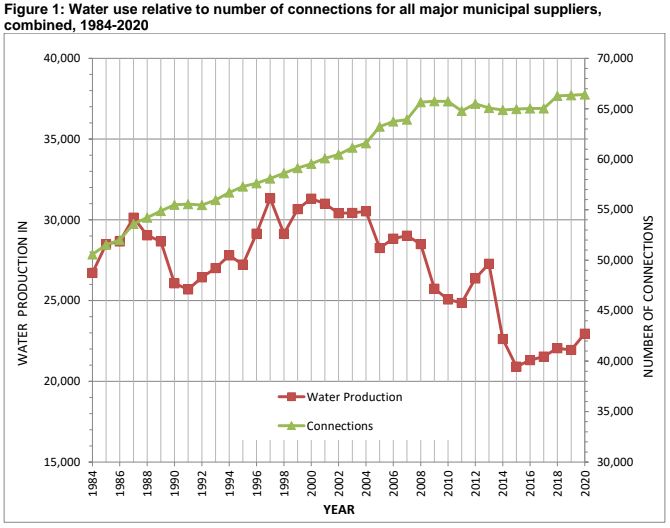

Among Santa Cruz County’s major municipal water suppliers, there were roughly 66,000 water connections in 2020, which is an all-time high, according to county data. Water demand however, peaked in 1997 and 2000 with about 31,000 acre feet of water, according to county data. Demand has fallen to about 23,000 acre feet in 2020.

A chart shows water production, or use, in acre feet and the number of water connections in Santa Cruz County. (County of Santa Cruz)

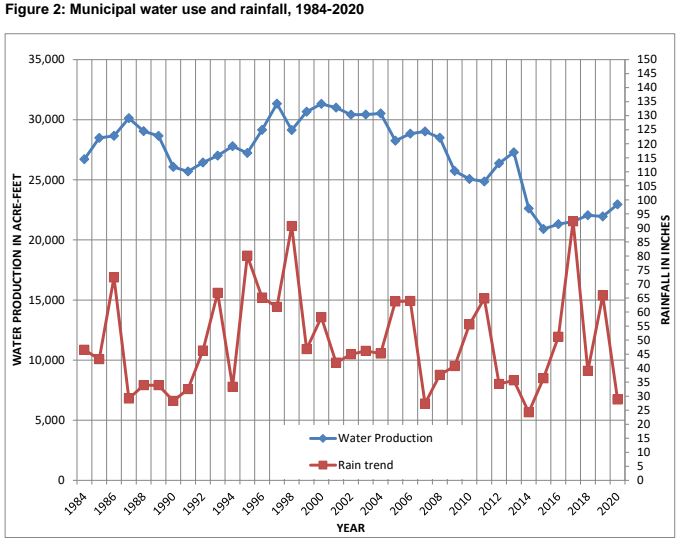

Annual rain varies, but water demand in recent years has been lower than in the mid-1980s in Santa Cruz County. (County of Santa Cruz)

Ryan, the county water resources manager, noted that water use was lowest in 2015 during a multi-year drought that parched the state. Even as the drought faded and population continued to increase across the county, water use has remained low, Ryan said.

Rosemary Menard, water director of the city of Santa Cruz, also has said that UCSC’s growth in recent years has not led to increased water demand. Water use has remained flat, Menard said.

Piret Harmon, the general manager of Scotts Valley Water District, said building codes and technology also have a lot to do with water demand.

Building technology

High-efficiency plumbing fixtures like low-flow toilets flush less water. Harmon said a single flush from a toilet in the 1970s could use up to five gallons of water. Modern toilets use a gallon or less. “People can still go to the bathroom as many times as they used to,” Harmon said. “But every flush is five times less.”

Water-saving technology also is required in new housing developments planned across the county. Modern apartment complexes are particularly efficient, housing a large number of people with a low water cost, Harmon said. And years of incentive programs have enabled single-family home owners to cheaply update aging fixtures. Water-efficient clothes washers and dishwashers also make a difference.

“Of course, more people will use more water,” said Harmon, of Scotts Valley Water District. “But we don’t count people. We count gallons.”

But conservation is just one way to protect water supply, said Menard, the water director for the city of Santa Cruz. “We’ve done what we can do” as far as increasing efficiencies and lowering water use, Menard said in an interview.

“We really have to solve the problem of getting additional supply here for the kinds of drought conditions that we’re going to be experiencing perhaps more routinely in the future, due to climate change,” Menard said.

Menard said that water rationing might be a reality this summer. But it’s still too early to make the call. “Just like the opera, it ain’t over ’til it’s over,” she said. “And the rainy season isn’t over until maybe even into April these days.”

Climate change means more uncertainty and potentially more drought. “Climate change is squarely on our radar,” she said. “This is a problem that has to get solved for the people that live here now.”

Potential solutions

Because areas outside the city of Santa Cruz have such a problem with sea water intrusion, projects have started to try to keep salt water at bay. The $90 million Pure Water Soquel project aims to refill the groundwater basin by injecting recycled wastewater supplied by the city of Santa Cruz underground. The purified wastewater provides a barrier to intruding salt water and an additional source of freshwater, water officials said.

Pajaro Valley Water Management Agency also uses some recycled water supplied by Watsonville to fend off sea water intrusion. It’s a technique used in other parts of California and the world to maintain a steady supply of water that is less reliant on the climate or weather.

Water officials said even if there were no population growth in Santa Cruz County in the next 20 years and no new homes were built, water supply and storage needs to be fixed.

“We have a problem for the people who live here now, and there’s no way to solve that problem without getting more supply,” said Menard, the Santa Cruz city water director.

Put another way, Menard said preventing new housing to try to solve Santa Cruz County’s water crisis wouldn’t be enough.

“We would have to reduce our (current) population by 20% or 30% or 40%,” Menard said. “That’s not happening.”

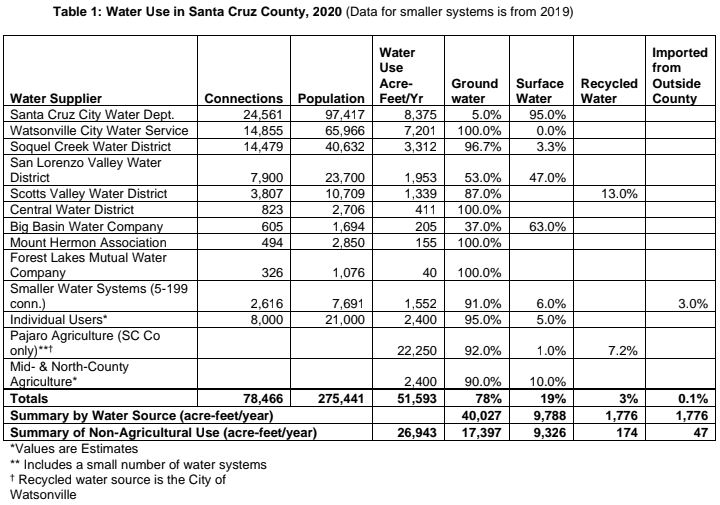

A table shows water use in Santa Cruz County. (County of Santa Cruz)

Questions or comments? Email [email protected]. Santa Cruz Local is supported by members, major donors, sponsors and grants for the general support of our newsroom. Our news judgments are made independently and not on the basis of donor support. Learn more about Santa Cruz Local and how we are funded.