Overhead power lines are expected to be put underground on Highway 236 at Acorn Drive near Boulder Creek, but it’s not clear when the work will happen. (Tyler Maldonado — Santa Cruz Local)

FELTON >> Many residents of the San Lorenzo Valley and Santa Cruz Mountains accept power outages as part of living in a rural area, but some prolonged outages this winter have prompted questions about what more can be done to prevent power losses.

Al Feuerbach, 75, said he and his wife were in their Soquel Hills home for 10 days without electricity during storms in late April and early March. It was the longest stretch without power that he could remember in 46 years of living there.

Their home’s battery storage system lasts for a half day under normal use, so they used it sparingly along with a propane-powered generator. PG&E’s estimated restoration times kept getting delayed.

“You’re kind of worn down by that point,” Feuerbach said. Their power was restored, then it cut off again 10 days later when another round of rain and wind toppled more trees into power lines.

To help prevent downed power lines and tree contacts — which also have ignited wildfires — PG&E leaders in 2021 pledged to bury 10,000 miles of electrical lines in California. Burying that many power lines would reduce wildfire risk by more than 70%, PG&E representatives said.

The utility surpassed its goal to put 175 miles of electrical lines underground by the end of 2022 — yet nearly all of that work has been done outside Santa Cruz County.

In Santa Cruz County, less than 1 mile of power lines were put underground in 2022, utility representatives said. About 7 miles of power lines in the county are in the process of being undergrounded this year — including projects that could finish in 2024 or later, PG&E leaders wrote in a statement. Weather, access and other constraints can slow projects.

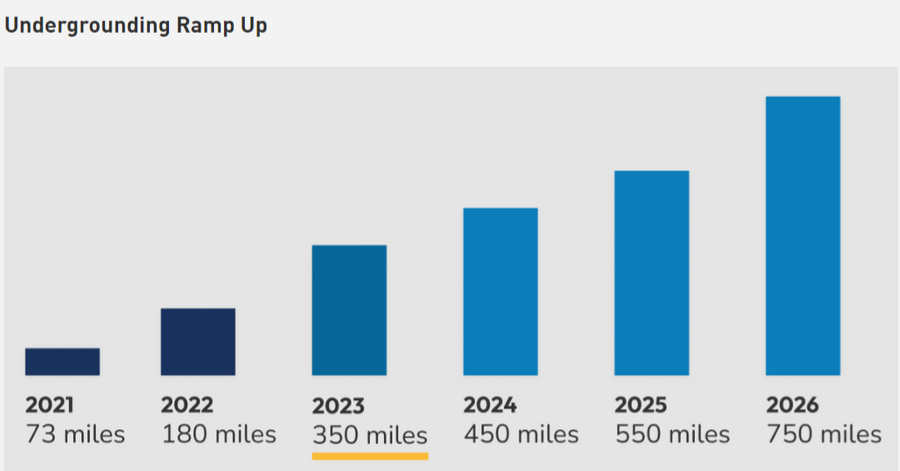

Less than 1 mile of power lines were put underground in Santa Cruz County in 2022, PG&E representatives said. About 7 miles of underground lines are in the works this year, including projects in planning and projects that could finish in future years. (PG&E)

Some of the power lines were put underground on Swanton Road and Highway 236 northwest of Boulder Creek — two places where many homes were destroyed in the CZU Lightning Complex Fire in 2020. More utility lines are expected to be undergrounded in those areas in the future, according to PG&E.

Areas chosen for underground work aim to efficiently reduce risk, said PG&E representative Jennifer Robison.

Statewide, most of the undergrounding has occurred in Butte County as a part of the wildfire-rebuild efforts in that area. “As these areas have already been affected by a wildfire, there is an indication that they are at an elevated risk and replacement infrastructure should be undergrounded instead of being rebuilt overhead,” Robison said.

Pacific Gas & Electric Co. leaders plan to add 350 miles of underground power lines in California this year. (PG&E)

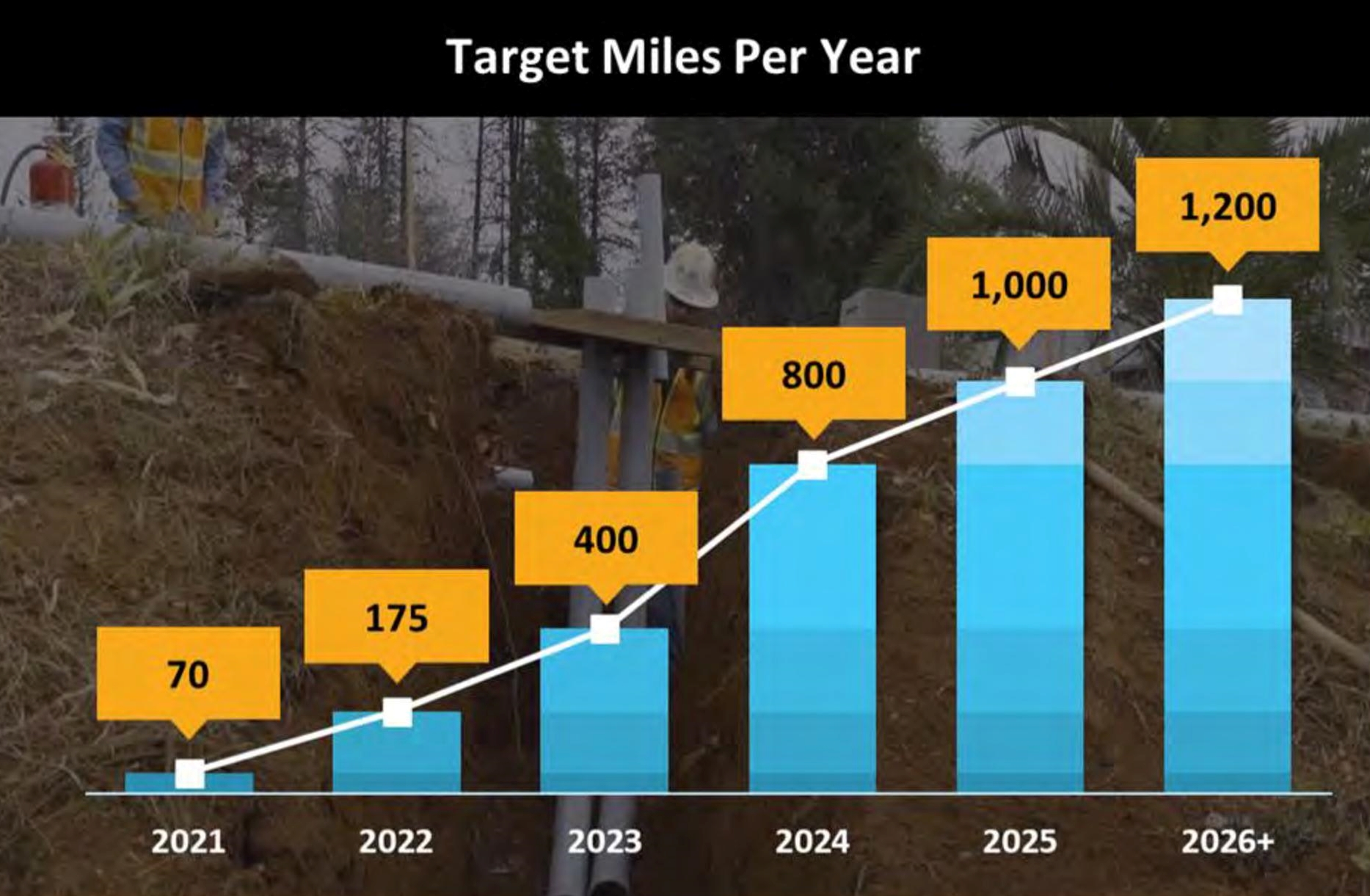

In an image from 2022, PG&E planned to put more miles of power lines underground than what it now targets. (PG&E)

Undergrounding power lines has some advantages:

- It reduces preemptive power outages meant to prevent wildfires, known as Public Safety Power Shutoffs. It also reduces outages from the “fast trip” Enhanced Power Line Safety Setting, Robison said.

- Once a line is underground, annual spending drops on temporary repairs and recurring expenses like tree work, Robison said. PG&E spent $2 billion on vegetation management last year, according to the utility.

In a local example of rising tree maintenance costs, contractors in 2011 charged about $1,800 per acre of vegetation management, said Bonny Doon Fire Safe Council president Joe Christy. Christy now budgets about $5,000 per acre of vegetation management due to the high demand for the work and shortage of previously available inmate labor from the Ben Lomond Conservation Camp.

Vegetation management projects can run as high as $25,000 per acre, Christy said. Traffic management during this work is the bulk of the cost and is often absorbed by Cal Fire or Caltrans.

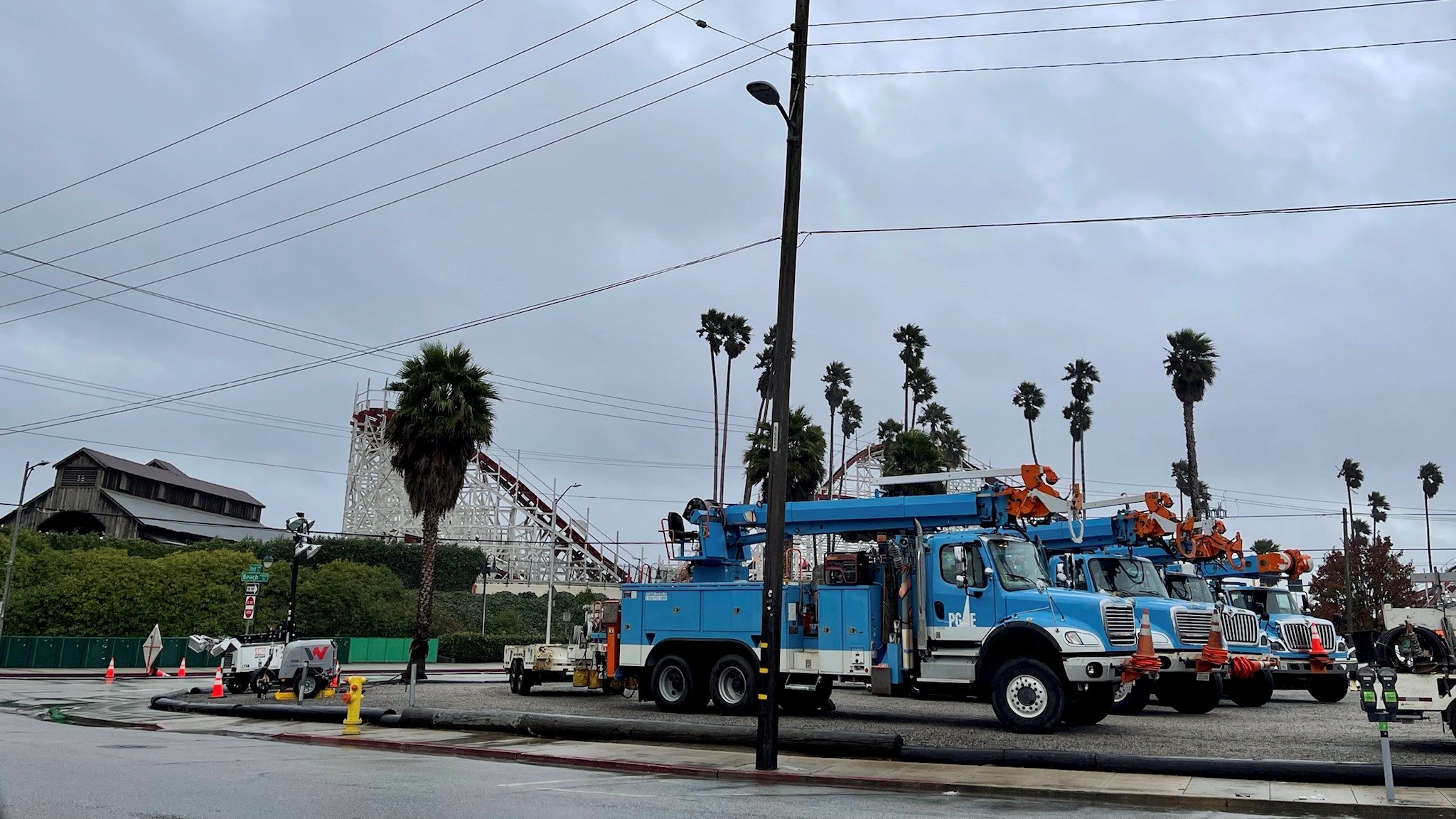

Pacific Gas & Electric Co. trucks are staged near the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk to respond to power outages during a storm in December 2021. (PG&E)

Costs and alternatives

Undergrounding power lines have downsides that start with its costs. PG&E estimates its cost to underground power lines at $3.3 million per mile. It anticipates that average cost to drop to $2.8 million per mile by 2026.

- Terrain and access contribute to higher costs to underground power lines in mountainous areas such as the Santa Cruz Mountains. Across the state, undergrounding power lines has historically cost $1.85 million to $6 million per mile, according to the California Public Utilities Commission’s estimates from PG&E, Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric.

- The public utilities commission estimates that the installation of insulated wire with fire-resistant metal poles would cost PG&E $480,000 per mile. While this approach is 40% less effective than undergrounding at preventing wildfires, it is also 16% of the cost of undergrounding, according to a California Public Utilities Commission report. Compared with typical overhead power lines, this approach also reduces the risk of storm-related blackouts, according to a federal report.

For ratepayers who would have to pay for some of the cost through their electrical bills, that might make alternatives more desirable. But for residents dealing with blackouts and whose communities are vulnerable to wildfires, that added safety might be worth the cost.

- Southern California Edison leaders have said that underground power lines take longer to construct, are more costly and more difficult to maintain and repair than overhead insulated wire, particularly in mountainous and rocky terrain.

- An underground power line can take two to four years to install. Insulated wires, known as “covered conductors,” typically can be installed in less than two years.

- Power outages caused by ground faults in underground power lines are harder to find and take longer to restore, according to the California Public Utilities Commission.

- Some underground facilities have exploded. A federal report cites increased maintenance from cooling stations needed to cool underground lines.

- There is also increased flood risk to underground lines in coastal regions like Santa Cruz County, authorities said.

Rural residents weigh in

Santa Cruz County residents are mixed in their estimation of the value of undergrounding power lines compared to the alternatives.

“The cost is staggering,” Bonny Doon resident Joe Christy said of undergrounding utility lines. Christy, 70, is the president of the Bonny Doon Fire Safe Council. He said he prefers insulated power lines to undergrounding.

“What are the costs of not doing anything” to reduce wildfire risk? asked Santa Cruz Mountains resident Sanjay Khandelwal.

Khandelwal, who lives near Summit Road and works in Silicon Valley, recently lost power for 10 days at his home. He said many of his neighbors want more lines to be put underground in part for safety and for long-term cost efficiency. He noted the reduced costs for tree work and maintenance.

“People don’t want to lose their homes,” he said. “They are looking at the Paradise Fire and drawing conclusions from the CZU Fire, and asking, ‘What if that happened here?” and “Why doesn’t PG&E underground everything?”

More than half of Santa Cruz County residents live in the high fire-risk Wildland Urban Interface, the highest percentage of any county in the state, according to a 2020 Santa Cruz County Civil Grand Jury report. Climate change and the number of rural county residents make for more expected victims of wildfires, floods, slides and power outages.

Christy said he also wonders if there are too many people living in an area where there have been major fires and floods. “We’re really lucky more people haven’t died in wildfires in this county. And it’s just getting worse,” Christy said.

Lynn Sestak, resident and fire advocate in her 60s near Summit Road, said communities have a large role to play in managing wildfire risk near their homes.

Sestak is the coordinator for a national program called Firewise to educate and empower residents to take on wildfire risk management. More than 40 Firewise communities in Santa Cruz County spent more than $6.1 million of their own money and worked for 78,000 hours to manage vegetation around their homes and communities.

Sestak said she’d like to see more public money go toward wood chipping programs similar to the one each spring from the Resource Conservation District of Santa Cruz County. Registration starts April 1.

“It really makes a difference. It helps local firefighters and makes (neighborhoods) safer to defend,” said Sestak.

PG&E representatives provide tips to prepare for power outages. (PG&E)

Cities and counties have initiated utility-subsidized undergrounding projects through Rule 20, but the program was designed primarily for aesthetic purposes in places of high population density. Developers and individuals can initiate their own undergrounding projects, but have to pay most of the associated costs themselves.

“Communities can send system hardening and undergrounding requests to their local PG&E representative, which we will consider against our risk model criteria,” said Robison. Customers with questions about PG&E’s Community Wildfire Safety Program, including undergrounding and vegetation management, can email [email protected].

Cedar Green, 31, grew up in Ben Lomond. He said he doubted that many people would move away from San Lorenzo Valley.

“I mean, people are going to continue to live out in those communities,” he says, pointing to the deep roots that exist in the area. “Because I grew up here, I have a pretty good community in this area. I have a lot of people I can go and stay with or that can help me out in situations like wildfire evacuations, or situations in which I don’t have power.”

During power outages in March, Green stayed with a friend in Soquel because it was too cold in his house without central heat. Not all of his housemates found shelter nearby, including one who left to find electricity to complete school work.

Green said he lived in Ben Lomond during the CZU Fire and dealt with blackouts around that time too.

Green said, “It’s just something you have to contend with.”

Read more:

- PG&E explains wildfire prevention strategies in Santa Cruz County – March 10, 2022

Questions or comments? Email [email protected]. Santa Cruz Local is supported by members, major donors, sponsors and grants for the general support of our newsroom. Our news judgments are made independently and not on the basis of donor support. Learn more about Santa Cruz Local and how we are funded.

Tyler Maldonado holds a degree in English from the University of California, Berkeley. He writes about housing, homelessness and the environment. He lives in Santa Cruz County.