Loch Lomond reservoir, which supplies water to the city of Santa Cruz, was 90% full in late March and about 86% full as of Friday, according to the city water department. (City of Santa Cruz)

SANTA CRUZ >> Santa Cruz County’s water agencies need more cooperation, a plan to recycle more wastewater and a united approach to adapt to drought, a recent Santa Cruz County Civil Grand Jury report concluded.

Since the report’s release this spring, water agency leaders said that some collaboration is already happening. Some water leaders added that the report’s recommendations have the potential to complicate an already complex system of water agencies — and it might not solve future water-scarcity problems.

Volunteers on the civil grand jury investigate public agencies, produce reports and make recommendations that require responses from elected leaders and agencies.

The civil grand jury found:

- Collaboration between water districts is “limited and narrow in scope.”

- No water districts or groundwater sustainability agencies have the money or resources to develop a drought plan for the entire county.

- There is no county-level agency charged with building drought-resilience projects across the county.

The civil grand jury recommended that by Dec. 31:

- The groundwater management agencies, the San Lorenzo Valley Water District, the Scotts Valley Water District, the City of Santa Cruz Water Department and the Soquel Creek Water District jointly publish a drought-resilience action plan.

- The county’s water districts jointly publish a plan for the full use of wastewater for water recycling. Full use of wastewater for water recycling should start by 2026.

- The boards of the Santa Margarita Groundwater Management Agency and the Mid-County Groundwater Management Agency extend their charters to include plans for drought resilience.

The report states that the county’s limited water resources and fractured leadership have led to an environment where water districts sometimes focus more on maintaining water supply for their customers rather than addressing the needs of the county as a whole.

“During interviews on district priorities, phrases such as ‘protect our districts’ surfaced. However, water in Santa Cruz County need not be viewed as a zero-sum game,” the civil grand jury wrote. “Unfortunately, there is no oversight agency or organizational structure in place to resolve conflicts and ensure that outcomes serve the greater good of the entire county,”.

The civil grand jury requires the county’s water agencies and groundwater sustainability agencies boards, as well as the city councils of Santa Cruz and Watsonville, to formally respond to the report’s findings and recommendations by Aug. 22.

Water supply and demand

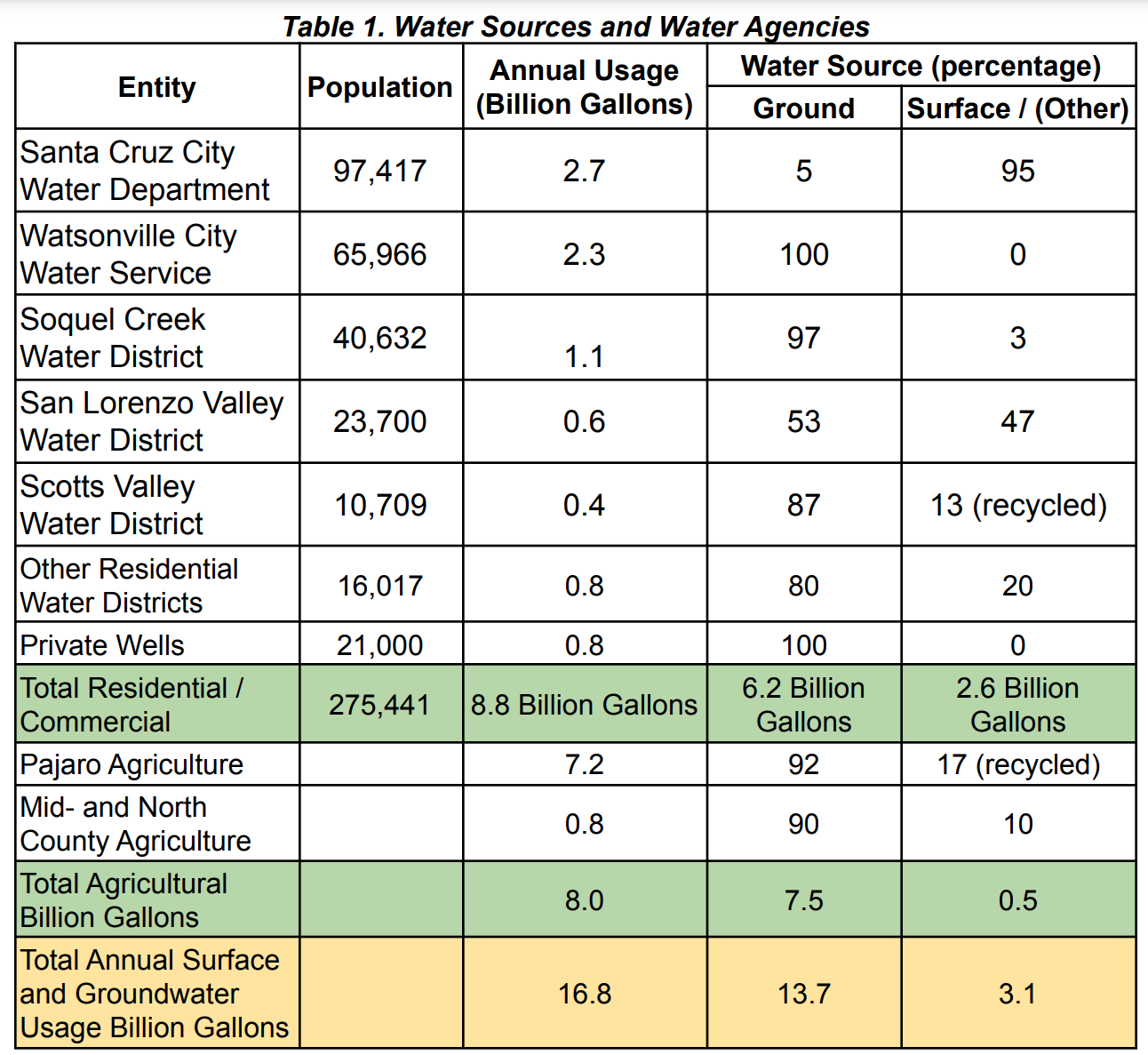

The county uses about 17 billion gallons of water each year. About half of that water is used for agriculture. The remainder is used by residents, businesses, governments and others.

Santa Cruz County is in “severe” drought, according to the National Integrated Drought Information System. January to June was about 16 inches of rain short of “normal” rain in that period, making it the second driest January to June in the past 128 years, the drought information system reported.

Climate change has led to longer and more severe droughts and increased odds for heavier and more infrequent storms, according to research from UCLA and other institutions. That variability makes the flow in rivers and creeks less predictable, and makes creating plans to store surface water more difficult, the civil grand jury report stated.

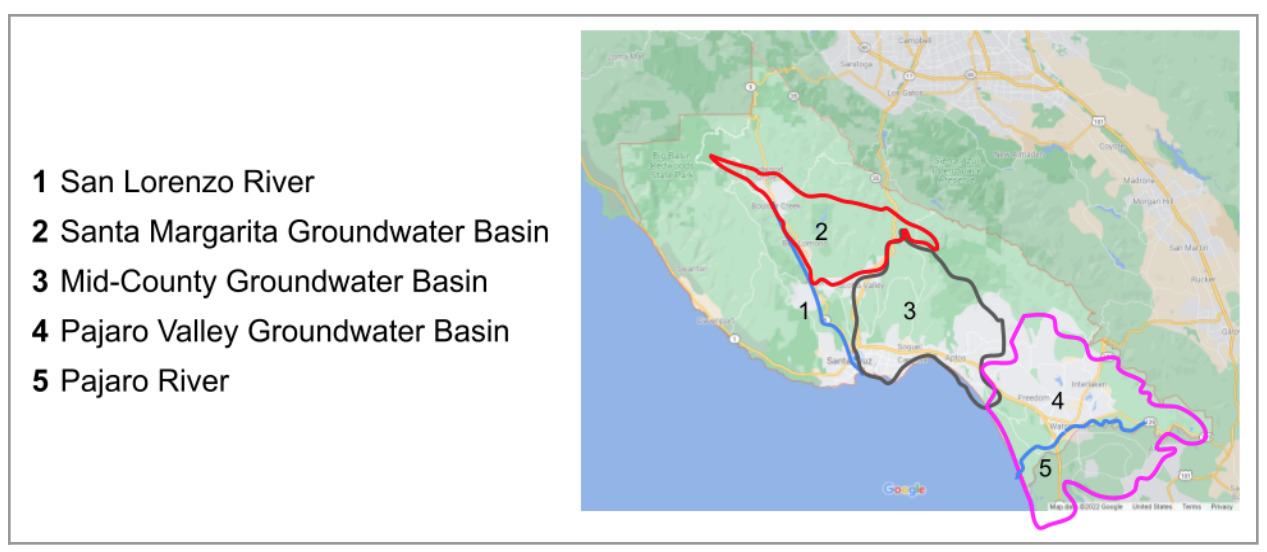

About 80% of the county’s water comes from underground aquifers. Other water comes from the San Lorenzo River and coastal creeks. Decades of climate change and heavy water use have made both sources less reliable, according to the report.

A map shows the major water sources within Santa Cruz County. Unlike much of California, all of the county’s water is sourced from local rivers, streams and aquifers. Most California counties receive water from other counties. (Santa Cruz County Civil Grand Jury)

Decades of groundwater use have depleted the Santa Cruz County’s three main aquifers. Two aquifers, the Santa Cruz Mid-County Basin and the Pajaro Valley Basin, are in “critical overdraft,” according to the California Department of Water Resources. As the groundwater has been extracted, saltwater from the cost has seeped inward, threatening the water quality of the aquifers.

Following a 2014 state law that requires groundwater to be sustainably managed, the Santa Margarita Groundwater Management Agency, the Mid-County Groundwater Management Agency, and the Pajaro Valley Water Management Agency must plan to maintain a stable source of groundwater.

In addition to the groundwater sustainability agencies, the county’s water is managed by five major water districts or departments, dozens of small private water systems and thousands of private wells. Each agency has its own rights to pump specific amounts of groundwater or divert a specific amount of surface water.

A table from the report shows who manages Santa Cruz County’s water. (Santa Cruz County Civil Grand Jury, Pajaro Valley Water Management Agency)

Within the past decade, the districts have started to work together to share water when it is plentiful. For example, in 2016, San Lorenzo Valley Water District and Scotts Valley Water District completed an intertie that allows the two districts to share water when one is in need.

Another example is the Pure Water Soquel Conveyance Project. To help block saltwater intrusion into the Santa Cruz Mid-County Groundwater Basin, construction recently began on a project to inject up to 500 million gallons of purified wastewater each year into coastal wells. The injected treated fresh water is planned to block saltwater from seeping into the wells.

Wastewater will come from the City of Santa Cruz wastewater treatment plant through new underground pipes to a new water purification plant in Live Oak. Work started in December on the plant, and crews have been installing pipes under city and county roads for months. Soquel Creek Water District will operate the injection wells.

Workers install a water pipe on Broadway from Riverside Avenue to Clay Street in Santa Cruz in February as part of the Pure Water Soquel Conveyance Project. (Brian Phan — Santa Cruz Local)

Water leaders react

Water district leaders said this month that a centralized drought plan isn’t as easy as it sounds. They also said it may not solve the county’s water supply problems.

Piret Harmon, general manager of the Scotts Valley Water District, said a county-level water agency would only add another level of bureaucracy to an already complex system.

“I wish it was simpler,” Harmon said. “It’s not, so we just have to work within the existing framework and make the best out of it.”

“There’s been collaboration for decades,” said Brian Lockwood, general manager of the Pajaro Valley Water Management Agency. The agency, which stewards the Pajaro Valley groundwater basin, spans across Santa Cruz, Monterey and San Benito counties. That makes a more centralized water system difficult to imagine, Lockwood said.

“When the report from the Grand Jury says there needs to be a Santa Cruz County water agency, you know they’re not thinking about Pajaro, where we have to work equally well with Monterey County Water Resource Agency and Monterey County water purveyors,” he said.

City of Santa Cruz Water Director Rosemary Menard agrees that robust collaboration already exists within the county.

“We’ve had for years really a very motivated self interest in working together to find regional solutions,” said Menard. “We know that no one is coming over the hill to save us.”

While fragmented water rights can make creating a centralized drought plan more challenging, Menard said many county residents appreciate the local control that comes with maintaining a smaller system.

“There’s that famous old saying that’s attributed to Mark Twain— ‘whiskey is for drinking, water is for fighting,’” said Menard. “Anybody who thinks we could wave a magic wand and tell people they’re not going to control their water rights anymore — that’s not gonna work.”

The City of Santa Cruz is in the process of altering its water rights to allow more flexibility in when and how the city uses water from the San Lorenzo River. The updated rules would allow the city to share water with the Soquel Creek, Scotts Valley, and San Lorenzo Valley water districts during periods of heavy flow.

The rules await approval from the State Control Water Board.

Some consolidation possible

While local water leaders do not foresee a county-wide water district, some small water systems are consolidating with larger ones. That’s due in part to a state law passed in 2021 that requires small water suppliers to proactively plan for drought.

The San Lorenzo Valley Water District merged with Lompico Water District in 2016. Now, they’re in the process of merging with Big Basin Water Co.

Harmon, the Scotts Valley Water District manager, foresees more consolidation across the county as small water systems confront the cost of replacing aging equipment. “I think they need to make a tough decision,” Harmon said of water agency consolidation.

Scotts Valley Water District faces its own tough decision, as the district considers partnerships with the neighboring Soquel Creek Water District or the City of Santa Cruz Water District. Last year, Scotts Valley and San Lorenzo Valley water districts considered a merger to operate more efficiently. But the idea faced pushback from some San Lorenzo Valley residents who feared that Scotts Valley development would consume a large amount of water.

Harmon said that attitude is a roadblock in creating a more interconnected water system. “I see a lot of pointing fingers,” she said. “I see a lot of language like, ‘Don’t come and take our water.’ So that is for me the biggest challenge.”

After the proposed merger was rejected by San Lorenzo Valley Water District’s board, Harmon said Scotts Valley Water is still exploring how to keep water supply stable and rates low in the coming years.

Wastewater recycling

Menard sees the possibility for wastewater recycling in the City of Santa Cruz to increase, but she doesn’t think the civil grand jury’s request for a plan to use all available wastewater by 2026 is feasible.

“There’s no way that resource can be fully utilized in four years,” Menard said. “The process of design, construction, environmental review, permitting, all takes a long time.” Depending on future water conditions and the success of aquifer recharge, the county may not require all of the city’s wastewater to be recycled to meet its water needs, Menard said.

Lockwood, the general manager of the Pajaro Valley Water, works with Watsonville city leaders to recycle 3,000 acre-feet of wastewater each year for farm irrigation in coastal Santa Cruz and Monterey counties. “We’re pretty much using all of the water that’s available for recycling throughout the summer, and then we use a portion of it in the wintertime,” he said.

A Pajaro Valley Water basin management plan from 2014 explored the possibility of expanding water recycling during the winter for injection into the groundwater basin. Costs prompted the project to be deprioritized in favor of other efforts.

“I think to some extent, we’ve checked that box by looking at how we can utilize all the recycled water available to us,” Lockwood said. “When we do the next evaluation of our plan within the next five years, I think we’ll take a close look at the status of the basin and determine if any additional projects are necessary.”

The agency is focusing on projects it hopes to complete by 2025 that include:

- Expanding the amount of water stored in College Lake from 1,000 acre-feet to 1,700 acre-feet, and building a new pipeline to connect the lake to its agricultural distribution system.

- Further developing facilities that divert fresh water from Harkins Slough that would otherwise flow into Monterey Bay into flooded basins that allow water to percolate into the aquifer. Similar facilities are being developed in Struve Slough.

- Constructing a new pipeline that will allow more farmers to use recycled water and water recovered from the slough facilities.

Read more about water

- Does more housing mean more water demand in Santa Cruz County? Feb. 15, 2021

- Water quality, rates could rise with Big Basin, San Lorenzo Valley Water merger – Jan. 24, 2022

Learn more about Santa Cruz Local and how we are funded. Santa Cruz Local is supported by members, major donors, sponsors and grants for the general support of our newsroom. Our news judgments are made independently and not on the basis of donor support.

Santa Cruz Local’s news is free. We believe that high-quality local news is crucial to democracy. We depend on locals like you to make a meaningful contribution so everyone can access our news. Learn about membership.

Jesse Kathan is a staff reporter for Santa Cruz Local through the California Local News Fellowship. Kathan holds a master's degree in science communications from UC Santa Cruz.