Santa Cruz Local offers its journalism free as a public service. But journalism can be expensive — and deep, time-consuming, investigative journalism is the most expensive of all.

We depend on memberships from people like you to make sure vital information can be available to all. Can we count on your help?

Editor’s Note: Santa Cruz Local’s Oct. 28 newsletter inaccurately stated that Proposition 15 would allow tax hikes on residential properties. The proposition would allow counties to raise taxes on commercial properties worth more than $3 million at more than the current annual 2% limit. The error does not appear in this story.

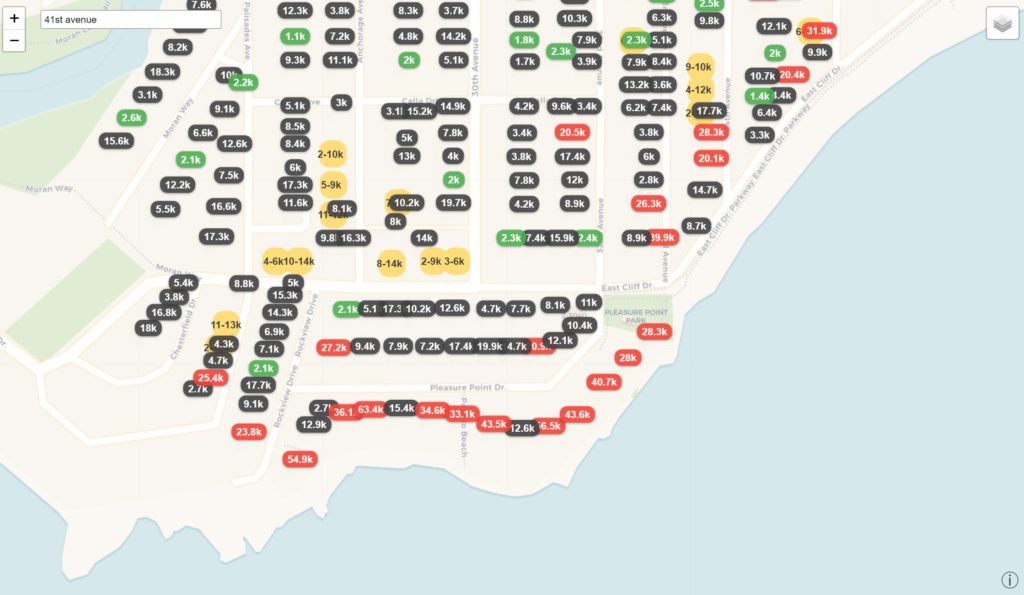

SANTA CRUZ >> Santa Cruz County residents have a new way to visualize property tax disparities with a searchable map that matches tax data with residential and commercial properties.

San Mateo-based engineer Ian Webster started in September by culling public data from tax assessor’s websites in San Francisco Bay Area counties. Santa Cruz Local member and housing advocate Kyle Kelley delivered him Santa Cruz County data. About four weeks later, Webster’s database was online with color-coded figures that showed gaps of $10,000 or more in annual property taxes — sometimes on the same street.

“My goal here is to present the facts and the data and allow other people or other projects to draw their own conclusions,” Webster said Monday. “Usually when I read about an issue that’s controversial and has viewpoints that I don’t see as consistent, my reaction is to find the data myself,” Webster said. “The data is public but in a very unwieldy format, so the whole project seemed to lend itself to data visualization.”

The Santa Cruz County data shows big differences in what homeowners on the same street pay in property taxes, and it also shows owners who pay the same bill for completely different homes.

For example, at least one homeowner on West Cliff Drive pays about the same $4,800 annual property tax bill that another homeowner pays in the Beach Flats neighborhood. A two-story home at 1514 West Cliff Drive has 5 bedrooms and 4-and-a-half bathrooms on 3,000 square feet of living area. It also has an ocean view at Mitchell’s Cove. Redfin values it at $1.8 million. The property tax bill was $4,867 in 2020, according to county records. It was purchased in 1971.

Meanwhile, 120 Raymond St. is a 2 bedroom, 1-and-a-half bathroom, 1,080 square foot home next to Beach Flats Park. Redfin values it at $745,000. The property tax bill was $4,850 in 2020, according to county records. It was purchased in 2012.

Webster’s maps and data already have fanned out online. A website called TaxFairnessProject.org recently posted a San Francisco Bay Area map that used Webster’s data and other data with permission. Phil Levin, a San Francisco-based leader of a “car-free neighborhood” startup called Culdesac, built that interactive map with help from others.

Levin’s website framed the vast differences that homeowners pay in property taxes as tax subsidies.

“Subsidy is defined as the difference between the actual tax and the tax the home would be paying if assessed at market value,” the website states. The site states that “market value” was sourced through publicly accessible, automated home valuation models. Examples include Zillow and Redfin.

California licensed home appraisers have said Zillow and Redfin are often accurate in data-rich places such as San Jose, but they can be inaccurate in other places in part because of fewer sales in an area and frequent lack of data on the interior conditions of homes.

With those caveats in mind, the Tax Fairness Project map shows an annual average “subsidy” of $12,000 in Los Gatos, $4,000 in San Jose and Campbell, and $12,000 in Los Altos.

Reactions online varied widely.

- One renter said her monthly rent is twice the money her landlord pays in property tax each year.

- A new homeowner posted a map that shows her annual property tax of $16,700 while her neighbors on either side pay less than $1,500.

- Another person tweeted, “Alternate framing: Hello, homeowner. This is how much liberals want to raise YOUR property taxes.”

Webster said he didn’t have an agenda when he started the project and still doesn’t. He simply wanted more data to understand Proposition 15 on the Nov. 3 California ballot.

Proposition 15 essentially would allow county tax assessors to raise property taxes on commercial properties worth more than $3 million at more than the current annual 2% limit — even if the property has not been sold and reassessed. It would not touch residential properties. County tax assessors would have to reassess commercial properties before property taxes could be raised. The measure is a way to roll back part of Proposition 13.

State laws

Proposition 13 was a 1978 ballot initiative that essentially capped residential and commercial property tax increases at no more than 2% annually unless the property was sold and reassessed. The change has kept money in the pockets of Californians who bought homes years ago — but it also has reduced funding for schools and roads, among other things.

“Property tax is the most important revenue source for the county,” Santa Cruz County staff wrote in this year’s proposed budget summary. “The county distributes property tax dollars to various government agencies and retains approximately 13% of the total property taxes collected, which is used to fund a variety of county programs and services.”

One argument for Proposition 13 was its intent is to keep senior citizens from being taxed out of their homes. Separate from Proposition 13, there is at least one state program — the Property Tax Postponement Program — that allows homeowners age 62 and older or who are blind or disabled to delay property taxes until death. The senior’s household income cannot be above $45,000 and the person has to hold at least 40% equity in the home, among other rules.

Also, California Propositions 60 and 90 from the 1980s essentially allows homeowners age 55 and older to buy a property of equal or lesser value and transfer the base year property tax value of the original home, according to the state Board of Equalization. Santa Cruz County allows such transfers for properties within the county, with restrictions. The original property had to be the person’s primary residence, for instance.

Other counties — such as San Mateo, Santa Clara and Los Angeles — allow such transfers within the county and also allow transfers from other counties, with restrictions.

Local comparisons

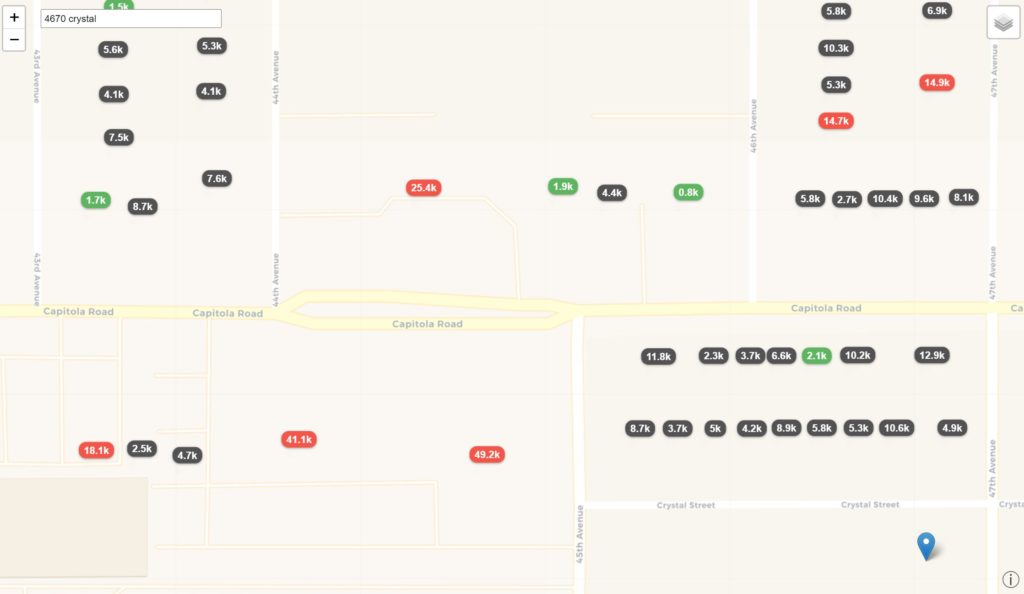

In Santa Cruz County, two comparable houses a few blocks from each other in Capitola tell a story about tax disparity. Both homes are in a neighborhood near the Department of Motor Vehicles office. They are in similar condition and not on busy roads.

A two-bedroom, two-bathroom home at 4670 Crystal St. in Capitola has 941 square feet of living area on a 3,180 square foot lot. It sold for $1.01 million in 2019 and the property tax was $12,175 in 2020, according to county records.

A two bedroom, two-bathroom home at 1761 44th Ave. has 826 square feet of living area on a 6,708 square foot lot. Zillow values it at about $914,000. Because it last sold for $131,000 in 1999, the property tax was $4,099 in 2020, according to county records.

Mapmakers Webster and Kelley said their intent was not to pit neighbors against one another. Homeowners and renters don’t control the system, they live in it, they said.

“I like all my neighbors a lot and I like my neighborhood. I think the problem that this shows is that it doesn’t have an easy solution,” Webster said.

“I was taken by how large and common these tax disparities could be,” Webster said, when asked his reaction to the maps. “Prop. 13 has benefitted some people and not so much others.”

Editor’s note: Kyle Kelley is a Guardian-level member of Santa Cruz Local. As a policy, stories that reference or quote a Santa Cruz Local donor who has contributed $1,000 or more include a written disclosure.

Stephen Baxter is a co-founder and editor of Santa Cruz Local. He covers Santa Cruz County government.